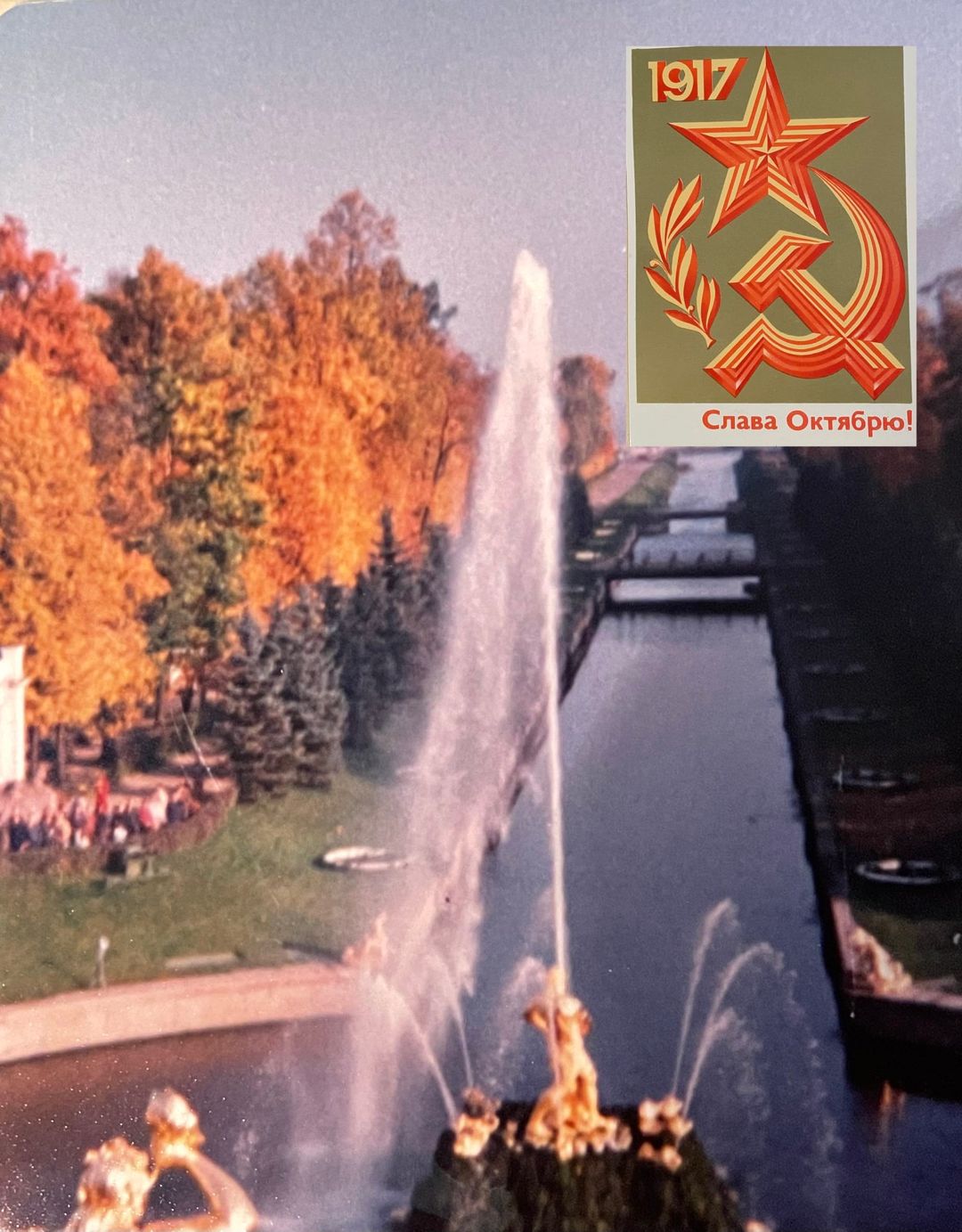

APRIL 28, 2022 – My tour of Leningrad was mostly self-directed—strolling along the canals, admiring the Italian architecture, the Bronze Horseman (statue of Peter the Great on horseback; commissioned by Catherine the Great); and inspecting the Aurora (the Russian cruiser that fired a blank shell to signal the beginning of the October 1917 Revolution).

In a letter home I described another aspect of my sight-seeing: “On my third day I visited Smolny Institute, site of Lenin’s headquarters. For unknown reasons I managed to slip by the entrance guards, but before I could find the room where Lenin worked, security personnel showed me the way out (the building [designed by an Italian architect and constructed in 1806 to 1808] was not a museum [as I’d assumed], but a government office).”

The letter continued: “As is my custom, I devoted considerable time to searching out the essence of contemporary life. That entailed a trip through the city’s largest ‘department store’—in fact, a jumble of dumpy display racks, tumbled-down counters, unruly crowds, creaking floors and the quick ‘click-clack’ of abacuses (the Russian ‘cash register’). For me it was an exciting, informative, thoroughly enjoyable experience.”

If Intourist and the KGB had assigned me a minder—an official tour guide—it was a guy who called himself “Plato.”

“On my way out [of the department store],” I wrote, “I gambled with the trots, food poisoning, or worse and sampled a ‘hot dog’ from a street vendor. Russian hot dogs, similar to Polish ‘dogs’ are merely greasy rolls stuffed with lukewarm who-knows-what-meat-by-products. As I chomped into my lunch, a Russian remarked in English, ‘Poison!’ I turned to him and inquired if he spoke much English and asked what he meant by ‘poison.’ He laughed and said—in perfect English—that Russian hot dogs weren’t very good. After a 10-minute chat there on the busy street corner, I invited him to a proper lunch. He recommended a place nearby that specialized in Georgian cuisine. His good taste was confirmed—the food, atmosphere, and service were superb.” The letter further disclosed that “Plato” was, by his accounting, a biochemist-researcher and former member of the Soviet-British Friendship Council.

The delectable meal, I concluded, was also a smooth con job. Primarily to impress me, I believed, “Plato” had extended effusive greetings to the restaurant staff. Moreover, before I could ask questions or compute the running price total, “Plato” had recommended (in English) all sorts of delicacies that I was “sure to enjoy” and rattled them off (in Russian) to the wait person. Ahead of the three tray-loads of Georgian specialties arrived several bottles of the finest Georgian wines, which had also been ordered (in Russian) without prior notice (in English) to me.

All was to be shared with “Plato,” of course . . . except the bill. Just when I realized I’d been stiffed, “Plato” said, thank you—in Russian (“Спасибо”). Who says there’s “No such thing as a free lunch”—especially in a Communist country?

I subdued my vexation. After all, the con had conferred some benefits on me, the mark: I’d enjoyed one helluva meal, enjoyed “Plato’s” amusing if not convincing monologue about life in the USSR (the thrust of which was, only people with access to “sensitive information” (amorphously defined) had to worry about the authorities). After lunch “Plato”—as “minder” or con man or both—gave me worthwhile personal, informative tours of St. Isaac’s Cathedral and the Peter and Paul Fortress.

When the hour arrived for my departure from Leningrad, “Plato” wished me a happy journey across Mother Russia.

“Спасибо,” I said.

(Remember to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.)

© 2022 by Eric Nilsson