AUGUST 22, 2022 – (Cont.) Yesterday afternoon I joked to some friends that “I like going to the U of MN Cancer Center so much, I even go there on Saturday and Sunday.”

Joking aside, this past weekend’s sessions, each for an infusion line flush, were brief and uneventful, except for the discovery that my able provider both times was the daughter of a lawyer/up-at-the-lake neighbor, which daughter I hadn’t seen since she was a little kid. She’s now a brilliant member of what I call the Division One Championship Team for Cancer Care. Because there’s minimal activity at the center on weekends, we had ample time to catch up on the past some 25 years. (Extra credit: I recruited her for a big-picture conservation project I have in mind for “up-at-the-lake” once I graduate from my course of treatment.)

After exiting the facility but before roaring off for home, I sat in the car for a moment to enjoy the luxury of having the entire block of street parking all to myself. I then pushed the ignition button, shifted into gear, and as if alighting from a park bench to continue a lackadaisical stroll, I slowly pulled away from the curb.

As I approached the first intersection, I noticed a guy in his late 20s out walking his dog along the sidewalk next to a leafy boulevard. Among the sunbeams poking through the trees, man and BFF glided seemingly carefree on a gorgeous day off. I wondered if the man might be a medical student or resident or a bright young member of the faculty at the University’s School of Medicine, but in any case, someone who works 18 hours a day, six days a week, and powers down to 12 on the day our forebears set aside for rest, for recharging mind and body.

My languid speculation triggered a distant memory that’s come full circle.

I recalled the day before the first day of class as an undergraduate; that last day of brash freedom before I entered the four-year ore mine of academic rigor. All to nearly that stage had been gloriously hope-filled. Deservedly or not, I’d won early admission to a small, prestigious, New England liberal arts college, and thus, for the rest of my high school senior year, I lived on cloud nine. Though I’d struggled mightily with the violin in my earlier time at the Michigan boarding school for the arts, I turned things around by practicing as hard as any of my far more gifted peers, and by the end of our time together, I could hold my chin higher than I’d ever imagined in the first few miserable months. (I’d fooled my way into admission to the place by standing on the shoulders of an older sister—an elite among the elite of academy violinists.)

I pulled off my senior recital before a “sell-out” crowed, who rewarded me with three curtain calls and a standing ovation. At first I thought it was a strange but generous attempt to extinguish my public humiliation: the performance had been such an out-of-body-experience, I had no recollection of anything except the final chord of the Franck Sonata. Only then did I recover awareness. I was certain I’d gone down in flames, but my kind friends howled and whistled and assured me that the performance into which I’d poured so much was worthy of ovation; friends far more gifted than I and who deserved the broad acclaim that would one day be theirs.

That performance, unforeseeable at the outset of my time at the school, was my crowning achievement there, and it catapulted me into a summer of optimism. If I could overcome debilitating self-doubt and conquer the violin (at least to the extent I had), why shouldn’t I bask in my callow sanguinity?

Upon arriving at college the next fall, worry set in as I took stock of my fellow students. Though I’d navigated without too much embarrassment among over-achievers in high school, this new crowd was playing for keeps in what seemed like a much higher-stakes game.

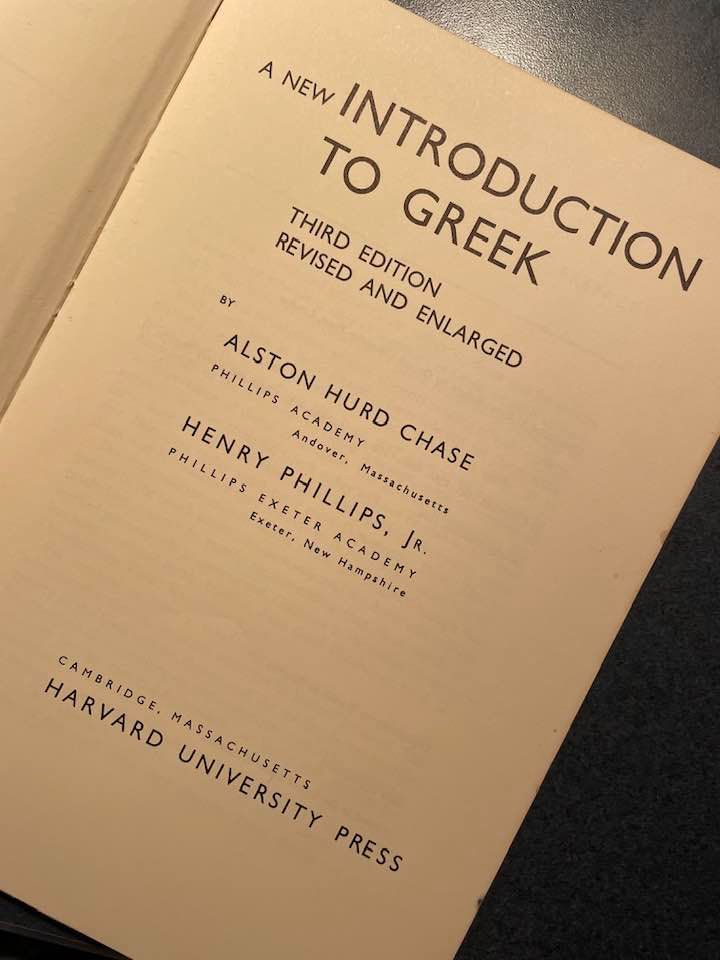

I feigned confidence in the company of others, but privately I experienced apprehension. The high school ovation that had affirmed victory over earlier self-doubt was fast losing its power. At this college, where academic champions numbered four times my high school student body of 450, there would be no academic accolades for me. I felt reduced to a raw, pitiful struggle between pass and fail. The first day of classes knocked me down even harder.

At the foregoing, unnerving point in yesterday’s reminiscence, my reflections jumped 50 years ahead to the present. Here again I stand . . . the day before the “first day of class.” Last December, I’d suffered greatly from symptoms; in January, with diagnosis. Many a dark night in the depths of winter, I’d searched for light and hope; for a daily hint of rescue from my plight; for music I’d performed or not; music with which I was familiar or not; something, anything to give me succor. In rather short order, I now say triumphantly, my condition improved. By May—the month of that ovation for the Franck half a century ago—I was feeling as fit as a fiddle. To stay that way for an extended time, nay—to squeeze more out of life, and give back tenfold—I must now “go to college”; I must get up early for the first day of class, and for every day thereafter, until I graduate magna cum laude, thanks to a medical care team that performs every single day—summa cum laude. (Cont.)

(Remember to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.)

© 2022 by Eric Nilsson