NOVEMBER 5, 2022 – Blogger’s note: Given the subject matter of this (lengthy) post, I found it difficult to split it into installments. I think you’ll understand why, assuming you read the post in its entirety.

I hadn’t touched my fiddle in a week, and before that, not in a month; maybe that’s why the dream after 7:02 this morning—I know the time, because that’s when I woke up, saw it was still dark out, checked the clock, dozed off again and . . . had the dream.

Retelling a dream, however enthusiastically, almost always falls flat on the ears of a captive listener, whose typical politely silent reaction is, “Your dream isn’t nearly as interesting to me as apparently it was to you.” But the dream I had this morning was so detailed—and so disturbing—I’m compelled to burden my readers with it . . .

I had a half hour to get to my lesson with “Mr. G,” as my parents referred to him in real life, and whom my sisters and I properly called, “Mr. Gilombardo.”

Of all the role models—outside the family—whom I had as a kid, our early violin teacher left the biggest impression. This was ironic: unlike my three sisters, who fell in love with the violin and pursued it professionally, I fought tooth and nail until my parents surrendered. Eventually, however, I came ’round to it on my own terms. Realizing what a young fool I’d been to have wasted this teacher’s musical inspiration, in my later teens I worked like crazy to make up for lost time and won Mr. Gilombardo’s applause. He died of a heart attack when he was all too young but at least he lived long enough to hear me redeem myself.

But back to the dream. I rounded up my case and . . . a bag full of miscellany, both useful and junk-worthy, tossed them into my car. Without driving anywhere (it was a dream), I found street parking in downtown Minneapolis two blocks from Mr. Gilombardo’s studio. I hadn’t been to a lesson in a while but knew the approximate location. Trouble started a block away. With a minute before start time, I realized I’d forgotten my violin in the car. Back I went.

Light rain was falling. Good thing my case has a canvas cover, I thought. Not a good thing, however, that I’d gotten my directions mixed up and was now a block in the wrong direction from the studio. I jaywalked to save time. A car struck me but gave me only a slight bloody nose. Yet—were my platelets low?

More troubles mounted.

I couldn’t remember the floor or number of the studio. I had a vague notion it was on the second floor, so after entering the old, brick, multi-story building, I quickly ascended a marble staircase one level. My phone rang. It was the “Multiple Myeloma Clinic.” I was afraid to answer. Besides, I was in a rush. The phone rang several times, then turned into a solid ring. People all around me looked annoyed. I was annoyed. I answered.

“We need to talk to you about your multiple myeloma,” said the caller.

“Not now,” I said and hung up, worried what it was that the clinic was calling about.

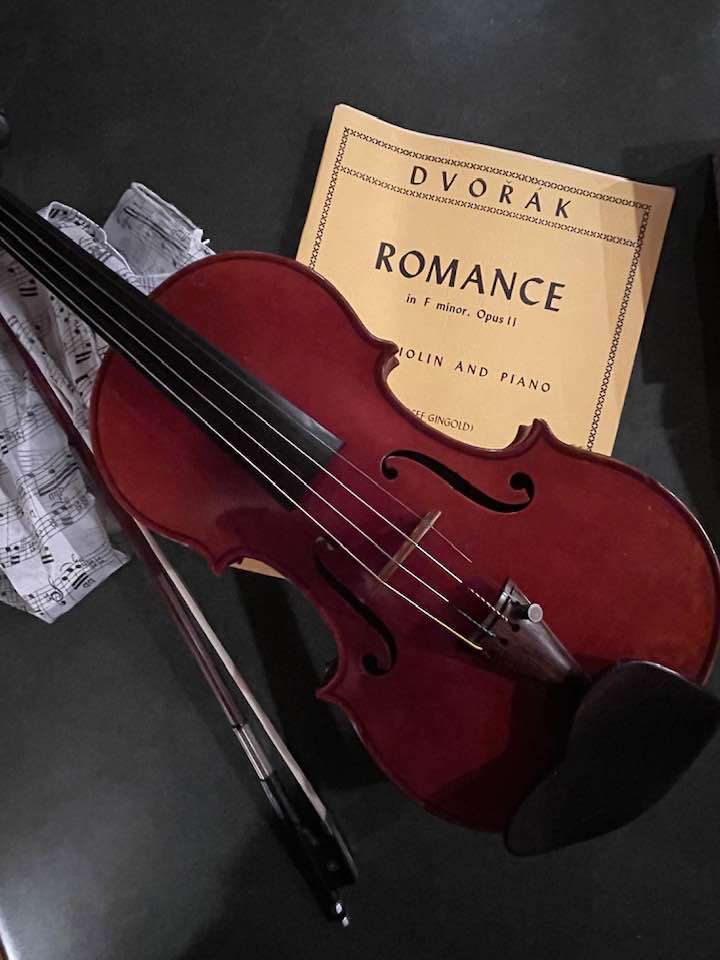

Before turning off my phone screen, I noticed it was now 10 minutes past my lesson time. Worse, I realized I’d forgotten my music—the Dvorak Romance. Plus, I still needed to find the floor and number of the studio.

The dream swept me out of the building entirely and onto the sidewalk outside the west end—I knew “west,” because it was late afternoon, and the sun was in my eyes. Four or five people stood next to me—lawyers, it seemed, with whom I was vaguely acquainted. One was wearing a black leather motorcycle outfit, scuffed-up helmet, and boots splattered with light-colored mud. The group bantered loudly. They ignored me when I asked where the studio was.

Just then a woman crossed the street and passed beside us. She was walking a small, squat, pet hyena, or rather, the hyena was walking the woman. It was on a leash, wore a sporty green “dog jacket” and had fur of a color nearly matching the jacket.

I ducked back into the building and found an old, wall-mounted directory. Listed were only tenants N through Z. I asked the concierge—an old guy with oversized glasses. “Where’s Gilombardo?” I asked.

“East wing,” he said, affecting a snooty British accent. “Studio 201.”

By now half my lesson time had passed. Next to the directory, elevator doors opened. The people I’d encountered outside were stepping aboard. None wore a mask. Concerned because I didn’t have an N95 mask, I donned a surgical mask, inhaled deeply and held my breath. I squeezed onto the elevator and heard one of the passengers tell dumb jokes.

On the ride up I realized I’d again forgotten my violin. I waited for the other riders to go the distance, then hit the down button. A high-end Mexican restaurant was on the ground floor—near the concierge desk; perhaps my violin was there, I thought (dream nonsense again). Sure enough . . .

After retrieving again my fiddle and bag—which had morphed from a baggie full of odd stuff into a canvas satchel filled with music—I checked my phone and saw only 10 minutes now remained of my lesson time. I didn’t know Mr. Gilombardo’s number or I would’ve called. Dvorak was missing from the satchel. I’d have to play from memory.

Finally, I reached the second floor of the east wing of the building. None of the studios had a number. An East-Indian appeared. He looked familiar. I asked if he was a tenant; he was. “Where’s 201?” I asked.

“Way down the hallway, I think,” he said. “It’s the only one marked.”

I scurried past a Christmas display, full of fake snow, birch trees, and decorations. A gold-lettered sign, “GILOMBARDO STUDIO” hung on the façade of a white dwelling that was part of the display. “Must be getting close,” I thought.

I ran, searching for “201” but at the end of the hallway wound up in a department store, full of kitschy merchandise. Two people wearing spacesuits were browsing. In a corner stood three women. They were the owners of the store—and the building. The eldest held a large ring full of keys. “Are you looking for Gilombardo’s studio?” she asked.

“Yes!” I said. “I’m very late for my lesson.”

“It’s right around the corner behind you,” she said. “He’s left, but here’s the key to his studio.” She held it out, still attached to the ring. “You can practice there. No one will mind.”

As I inserted the key, I realized Mr. Gilombardo wasn’t returning. I then woke up, remembering as I did that he was dead. I felt terribly disappointed and horribly guilty that I hadn’t reached his studio in time . . . but it was a dream!

Shaken, after breakfast I pulled out my violin and . . . practiced. I played the first Bach I’d studied with Mr. Gilombardo and recalled how he’d played it and what an impression his interpretation had made.

(Remember to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.)

© 2022 by Eric Nilsson