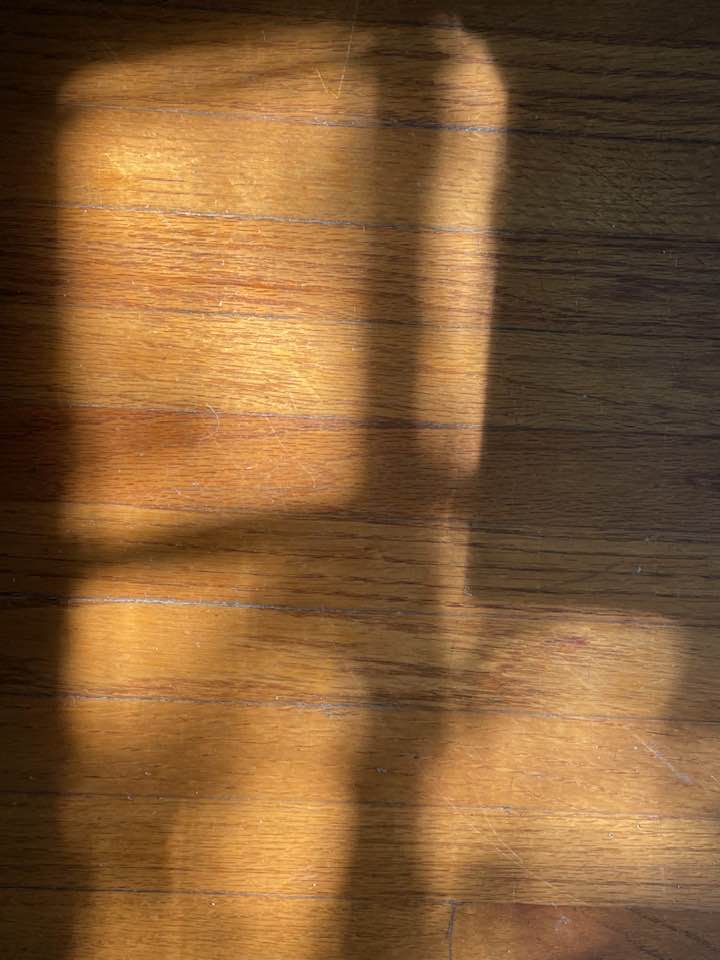

SEPTEMBER 14, 2022 – (Cont.) This morning I entered a room of our house and discovered a patch of sunshine on the old, oak floor. This unexpected burst of light lifted my spirits and renewed my energy. In the reigning silence I heard my father’s voice. “The sun is the source of all life on earth,” he’d often say, as we walked through sunbeams filtered by the woods of Björnholm. One of Dad’s signature qualities was his awareness of the big picture and his frequent reference to it—despite his almost excruciating penchant for details associated with objects close and matters immediate.

As I contemplated that ephemeral patch of sunshine, I was transported a million miles beyond the moon, to a place where I could see earth and sun in perspective. I imagined the effect of seeing from a vast distance, what we take for granted as we go about our hurried, woeful lives: the clock-like constancy of the earth’s rotation and revolution and the sun’s uninterrupted life-giving light and warmth as our planet dances around its stage. Yet even down here on earth, juggling and navigating through the demands, conventions, and human constructs of our modern world, if we’re on the lookout, we can connect with the “big picture,” simply by being on the alert for a patch of sunshine on a tree trunk, on the side of a neighbor’s garage, or . . . on the old, oak floor in a quiet corner of the house.

Inspired by that patch of sunshine on the floor, I went for a rigorous two-mile walk—the longest since my expedition began a full month ago. I finished the outing without complaint—and without needing a nap.

Besides, I had an appointment to keep—one more blood draw via the port-catheter, followed by removal of the tubes that made me part Dracula and part Frankenstein. I’d never grown accustomed to the arrangement, though thankfully, despite detailed instructional sessions about line maintenance and bandage replacement, my wife and I never had to attend to such matters—the clinic took care of everything daily over the 29 days during which I carried such a freakish appendage to my upper right chest.

As it turns out, my treatment regimen since January, and most particularly the transplant expedition, haven’t diminished my natural squeamishness. In fact, just the opposite. Some of the invasive procedures I’ve had to endure have made me ever more sensitive to being poked, prodded, infused, and otherwise treated by my precious teams of caregivers. As much as I was looking forward to the day when I could escape Dracula and Frankenstein, I dreaded more the process by which the six-inch “line” would be yanked from a major blood vessel running up the right side of my chest to the collar bone. I felt nauseous just thinking about it. The Ativan I took in advance (recommended by a nurse) had no effect whatsoever.

With trepidation (and fear of vomiting my lunch), I was led by “Scott” into the procedural theater. It included an imaging machine (having nothing to do with the line removal, though apparently it is used for line installation—of which I have only the vaguest recollection, thanks to sedation on that occasion), a patient bed, a supply cabinet and several chairs. I imagined it as the surgical room aboard a spaceship bound for Mars.

Scott was perfect for the job. With years of experience, he, like all of his colleagues at the clinic, was able to plunge immediately into a reassuring rapport. He had a quick wit, a ready sense of humor, and he didn’t let on if he thought any less of me for being an avowedly squeamish chicken of the first order. In fact, he gracefully embraced my anxiety and transformed it immediately. “Tell you what,” he said, “I’ve got a supply of lavender. You like lavender? A couple of sniffs of it and you’re gonna feel like this is a walk in the park.” I thought of a perfume shop I’d visited decades ago in Cairo, Egypt, and how I’d emerged from the shop as if I’d found nirvana.

I stuck the lavender inhaler under my (double) mask and took a deep breath. “Ahhhh!” I said, then waited a beat or two. “But Scott, you didn’t tell me it was a hallucinant!”

“Oh yeah?” he laughed.

“I mean, what’s that Mickey Mouse hat doing on your head?” I was kidding, of course, but the spontaneous image that I’d conjured in full consciousness put me at greater ease.

With a perfect level of detail for my consumption, Scott described the process, and his confident assurance chased away any remaining hint of nausea.

“The P.A. who’ll be doing the heavy lifting is named . . .” Scott said, before I interrupted.

“. . . Hold the phone, Scott! ‘Heavy lifting?’ I fail to see how this procedure involves heavy lifting of any kind, unless you’re confusing ‘heaving lifting’ with ‘heavy pulling,’ or heaven forbid, ‘heavy yanking’ of this Frankensteinian plastic tube out of my precious blood vessel.”

Scott laughed. “I was speaking strictly figuratively,” he said, “But in any event, the P.A. doing the work will be Chris Greisler.”

“Fritz Kreisler?!” I said. “The famous Austrian violinist who died in 1962?” Scott hadn’t heard of Fritz Kreisler, so I was happy to call up the memory of a great musician. Scott was interested to hear about a rock star of the classical music world of the first half of the 20th century.

As he prepped my skin for the removal of the line, I asked Scott about his background and discovered that he was an accomplished artist—a pointillist but also a painter, an illustrator, and sculptor. I convinced him he’d managed to combine one calling with another; that his artistic background was manifest in his rapport and bedside manner and most certainly complemented his total command of the technical aspects of his medical work. It was a delight to see and hear his reaction to this observation.

Minutes later, Mr. Greisler appeared fully suited up for the procedure. I told him that when Scott had first mentioned his name, I thought he’d said, “Fritz Kreisler.” Again, I was able to spread the word to the uninitiated, and I was greeted by the same interest that Scott had expressed. The P.A.’s college major, I discovered, was medical psychology, and upon learning this, I told him he’d have a field day with me, if he hadn’t already figured that out. His laughter calmed my nerves even further.

Only a few tense (my scale) moments brought the slightest hint of discomfort. For no more than 10 seconds, I distracted myself by a method I described aloud as I deployed it. “Now I know why we have 10 toes,” I said.

“Why?” asked Scott and “Fritz” at once.

“If you wriggle your toes against the soles of your shoes, it helps you see more combinations of patterns on the ceiling tiles—and that effort creates an excellent distraction from whatever it is you’re doing to my chest!”

“Whatever works for you—we’re in full support of it,” said Fritz Kreisler, playing along.

Before I knew it, the procedure was over, and Scott was giving me care instructions for the slight wound that he assured me would “soon scab over.”

I told Scott and Chris that one positive benefit of my chicken status is my correspondingly heightened gratitude for their expert work. It truly meant something to them to hear that and underscored how important it is to thank people—always and genuinely—for what they do so well.

Scott’s instructions included, for the next couple of hours, no bending over, no lifting, no lying down. Tomorrow—moderate exercise, such as an “easy round of [. . .] golf.” I don’t yet have clubs, lessons, or technique. But I know where to find a golf course—otherwise known as . . . my local scale model of Switzerland, exactly a mile from our house.

If I can’t ski (or golf) tomorrow, at least I’ll get to see the Swiss Alps—exulting in “big picture” sunshine (Cont.)

(Remember to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.)

© 2022 by Eric Nilsson

1 Comment

I am also a scaredy-cat. Nice to have company! Good job.

Comments are closed.