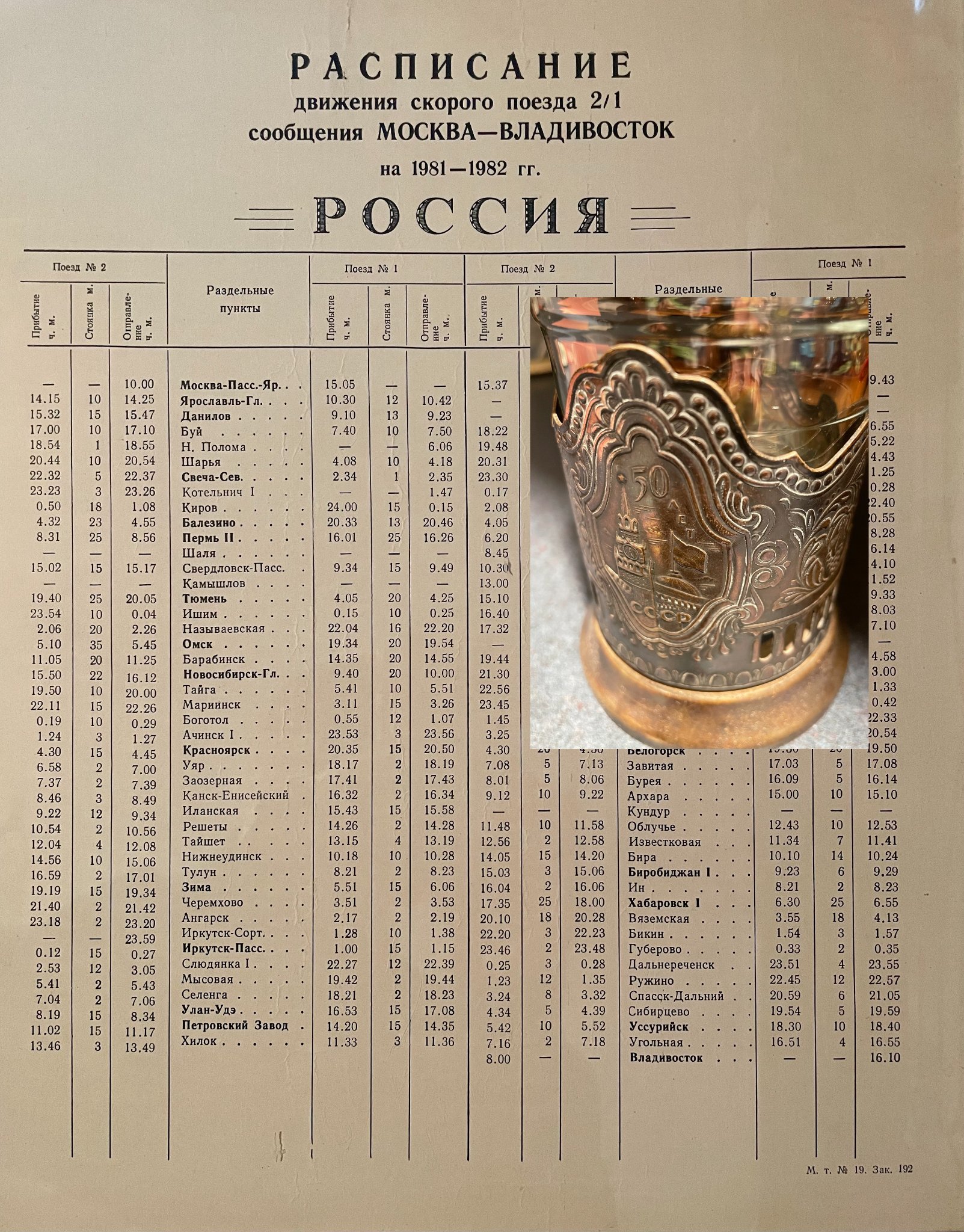

MAY 8, 2022 – My other prized souvenir from the Trans-Siberian train (see yesterday’s post) was the (real) silver, commemorative Russian tea glass holder impressed with an image of the Kremlin, “CCCP” (“USSR”), and “50,” marking the half-century since the (“glorious”) October Revolution of 1917. These exquisite tea glass holders were available for use aboard the train by every passenger in the carriage. Since the then current year was 1981, 14 years past the 50th anniversary of the Revolution, the age of the holders added to the nostalgic ambience of the rail journey. On the last day of our trip, Yuri, the chief of the train crew, awarded me a freshly polished version of the coveted tea glass holder—and tea glass*. “For my American friend!” he said in English, as he made the ceremonious presentation. I was moved by the gesture, and the souvenir has followed me to a prominent shelf in every office I’ve ever occupied since the Grand Odyssey.

Yuri was a character. He was funny, animated, engaging, interesting, well-educated, and well liked by his subordinates. I spent many hours in his office-compartment talking with him about a wide range of subjects. On one occasion we discussed religion, and on this matter, he explained that he fully subscribed to the Party’s embrace of atheism. A day or two later he was telling me about a driving incident in which he nearly “bought the farm.” He was driving on some country road in the rain when he rounded a curve and was about to run smack into a horse-drawn wagon. To avoid a collision he drove off the road and plunged down a steep embankment straight toward a tree. As I was held in suspense over what happened next, he crossed himself. Upon seeing this gesture, I said, “But you’re an atheist!”—upon hearing this he laughed. “Until problem,” he said, “to God I pray!” Yuri then clasped his hands as if in prayer and raised his chin upward. Whereupon, I laughed, and he resupplied my glass with vodka.

Yuri’s humor-filled candor appeared in other conversations, as well. My favorite was the one in which I raised the issue of endemic alcoholism among Russian workers. I brought up the subject by drawing a picture of a factory (a rectangle with smokestacks), a stick-figure representing a “robotnik” (worker), and a bottle of vodka. I then gestured like a man drinking by placing a thumb to my lips and leaning my head back. I next drew a clock face on which I placed the hands at 11.00 h. “Nyet, nyet, nyet!” Yuri protested with folded brow. He picked up the pen, crossed out the clock face, drew another, and placed the hands . . . at 9.00 h. He then laughed in acknowledgment of the problem of workers showing up sauced.

When I asked Yuri, “Tell me the truth—was the KGB to be feared?” he revealed that his brother and uncle were KGB agents. He assured me that the KGB did not hover over everyone or intrude ubiquitously on their lives. Just when I wanted to believe him, he allowed that just prior to our departure from Khabarovsk, the KGB had met with him to discuss the sole foreigner aboard—Me!—and whether I was merely a tourist or had other business.

On the subject of personal freedom, I didn’t detect among the Russians on the train any hint of the feeling of repression that I’d observed in Hungary and Czechoslovakia. Concomitantly, the Russians hardly seemed likely to rebel against their government. As I reported in my letter home, “What’s happened in Hungary, Czechoslovakia, and Poland is inconceivable in the USSR. Not only because of the brute power of the government but because the people themselves seem to have little of no revolutionary spirit. Symptomatic of the social stability (or perhaps a main contributing factor) is the apparent cohesiveness of families. At train stops I often saw whole families greeting or bidding farewell to one of their members. Also, children are revered but not spoiled, and they are remarkably well disciplined.”

The supreme irony of Russia, I think, is that one of history’s most significant revolutions occurred within one of the world’s most conservative societies (Cont.)

______________________

*See my post of 7/13/2019, Relics from the Past (Part II of III). Over several decades I’d manage to keep that tea glass intact across thousands of miles of travel and multiple office moves. Then one day I entered my office to find the glass shattered on the floor. Ironically, Khrushchev on Khrushchev, a book by Sergei Khrushchev, son of the Soviet premier, Nikita Khrushchev, which book had been standing directly behind the tea glass on a book shelf, had fallen forward, knocking the tea glass onto the floor, where the glass shattered—in the fashion of Khrushchev’s premiership in October 1964. The notable thing about that earth-shattering (at least in the realm of geo-politics) event was that Khrushchev decided not to fight his adversaries, thus assuring a peaceful, if involuntary, transition of power.

(Remember to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.)

© 2022 by Eric Nilsson