MAY 2, 2022 – “At 9:30 h. on [October 2],” I wrote home, “a big, black limousine picked me up at the hotel and whisked me to one of Moscow’s 11 train stations.” It was the Yaroslavski Station—western terminus of the Trans-Siberian Railway.

For the next 16 days, I traveled across seven time zones to the Russian Far East—and back. It was the best way to begin understanding the “riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma” that is Russia. My letter home gave a detailed account of the dozens of people I met aboard the train and the remarkable scenes and scenery along the route.

Before recounting those highlights and encounters, however . . . and my sojourn in Irkutsk at the foot of Lake Baikal, a side-trip to a Siberian village, and my stopover in Khabarovsk, I described the Trans-Siberian train itself.

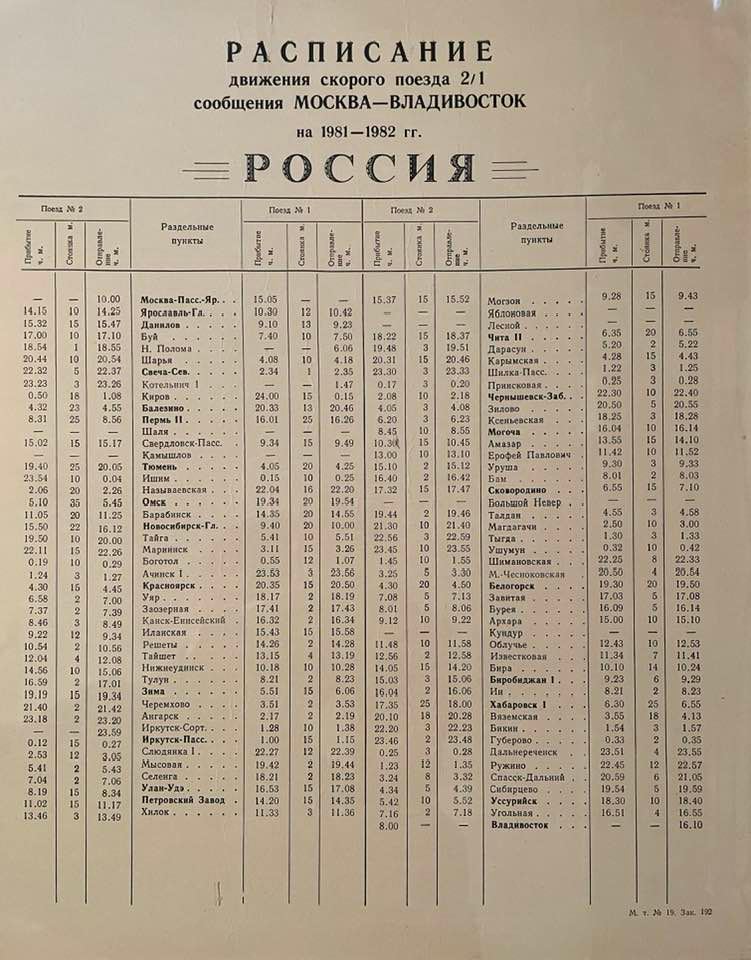

“First, a few facts,” my letter read. “The Trans-Siberian Railway was completed in 1904, linking Moscow with the far flung Russian East. Prior to the existence of the railroad, it [could take] up to two-and-a-half years for correspondence (travelers) to cross the Russian Empire. The rail route goes from Moscow north to Danislav (after crossing the Volga River) and then cuts due east to Perm on the European side of the Urals. The first Asian stop is Sverdlovsk, southeast of Perm. Now the line is in Siberia, and it continues east through Omsk and Novosibirsk. After Krasnojarsk, it swings south to Irkutsk and along the south shore of Lake Baikal to Ulan-Ude. Next comes Cita, Mogoca, and Magdagalici near the Chinese frontier. Finally the train heads southeast to Khabarovsk and another 700 km due south to Vladivostok. Visas for Vladivostok are not granted to foreign tourists, so travelers going to Japan must take a special train from Khabarovsk to Nahodka, the port for boats going to Yokohama. The total distance from Moscow to Vladivostok is 9,289 km [5,772 miles].

“The train itself, the Россия (pronounced ro-SEE-a) [“Russia”] consists of 16 to 18 carriages, including two restaurant cars. Locomotives are changed numerous times, and both electric and diesel engines are used. The carriages are made in the DDR [East Germany], and like most European trains, they are compartmentalized. Each of the seven compartments per carriage has four sleeping berths, and for a nominal fee, linen, including a towel, is provided.

“The attendants live at one end of the car, and their duties include assisting passengers on and off the train, house-cleaning, stoking the car furnace, and serving delicious Russian tea. The tea is served from a 25-liter hot-water tank at one end of the carriage.

“Each car is heated by a coal-burning furnace and each day, at one stop or another, coal supplies are replenished. This fuel is dirt cheap (Siberia is loaded with coal), and I want to stress the word ‘dirt.’ My clothes are terribly sooty, and my lungs probably aren’t too pink either. (By the way, smoking in compartments and corridors is prohibited.) Between Moscow and Khabarovsk, the train stops 69 times; 79 times between Moscow and Vladivostok. Stops are between one and 25 minutes long. On the seven-day trip, the train is rarely more than five minutes off schedule. The train timetable and station clocks are on Moscow time—seven hours behind Khabarovsk/Vladivostok time. The restaurant cars and most passengers, however, adhere to local time. Food aboard the train is ridiculously cheap—for a three-course meal (and satisfying one at that), I never paid more than one rouble, 50 kopeks (about $2.00 officially; [much less] black market]). Service in the restaurants was unfailingly quick and cheerful (unlike most city and hotel restaurants).” (Cont.)

(Remember to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.)

© 2022 by Eric Nilsson