MAY 30, 2023 – (Cont.) Second: the plight of women. This is one of history’s great challenges. With some notable exceptions, women have shouldered burdens and abuse disproportionate to their 50% representation of humanity. (In the case of extremist Ukrainian atrocities against the Poles of Volhynia, women and children were a sizable majority of the victims.) Why is this so? It’s certainly not a function of lesser strength or fortitude than men. If it were otherwise, the species would’ve gone extinct soon after it evolved to full homo sapiens status. Clearly, however, biological differences shaped the cultural forces that developed in nearly every society, except in rare instances of isolation from outside influences. Some people of retrograde beliefs—the Taliban, Iranian theocracy and puritanical extremists within other faiths—still advocate suppression of women, but recently civilization has begun to realize the benefits of full female emancipation. The film, though, is a reminder that the stone age in this regard was long-standing and not long ago.

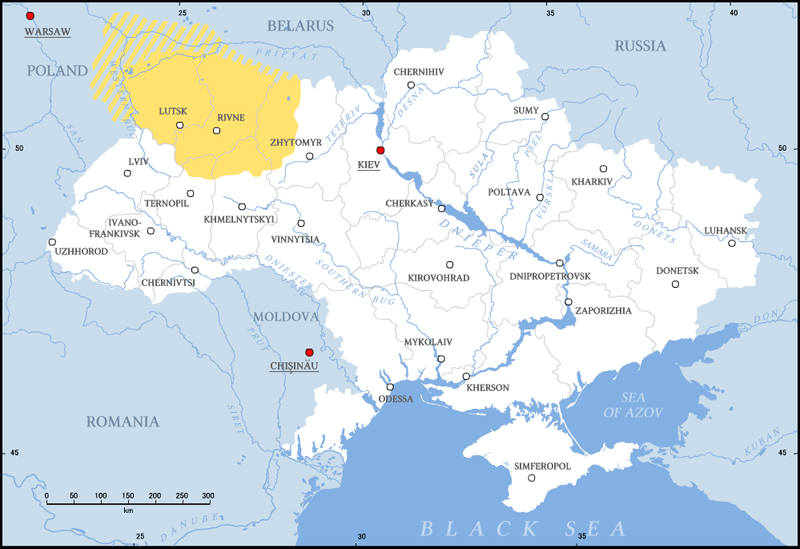

The third element of Wołyń that strikes home is the role of religion in conflict. Wołyń / Volhynia marks the transition zone between Western Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy. Centuries of strife in the region produced antipathies among the inhabitants of what is now eastern Poland, southwestern Belorussia, and northwestern Ukraine. (Welcome once again to the broader human condition.)

Though all of Christianity emanates from the same origin, the devil—as always—is in the particulars of Christianity’s evolution: Whose king, whose army prevailed over your ancestral lands a thousand years ago? Which brand of which branch of which schismatic offshoot of liturgical ritual did your great-great-great grandparents’ village adopt—or were they forced to join?

In Wołyń, by the time German panzers rolled in after the launch of Operation Barbarossa in June 1941, Orthodox priests stood loud and tall, commanding their congregants to destroy their Polish oppressors, while Polish priests, meanwhile, did the same in reverse. There were exceptions, of course—priests of the Eastern faith and those of the Catholic persuasion preaching brotherly love. But agents of the anti-Christ on both sides of the historical divide had the greater influence.

At the close of the film, casualty statistics are projected for the national-religious conflict between Poles and Ukrainians; Catholics and Orthodox Christian. The Nazi – Soviet atrocities, which dominate most modern depictions of that horrific epoch in history, are not central to the film. They are only contextual and catalytic.

Last year a couple of months after Putin invaded Ukraine, I spoke with Jurek, a good Polish-born-educated lawyer friend of mine who was preparing to visit his elderly mother in Rzeszòw, near Przemyśl on the modern Polish-Ukrainian border. He’d spoken with her by phone shortly before our conversation, and on the subject of helping Ukrainian refugees pouring into Poland, Jurek’s mother had said, “We have to help them, but we cannot forget what they did to our people.” When I asked about this, Jurek gave me a short history lesson, highlighting Stepan Bandera, the far-right leader of the radical, militant wing of the OUN-B (“Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists-Bandera”), who, as the son of an Orthodox priest, was hellbent on massacring Poles. I left it at that. I was much too focused on the current clash between Russians and Ukrainians—and Russian Orthodox and Ukrainian Orthodox churches.

From a broader perspective, Wołyń is a reminder that Putin’s motives, wholly out of synch with contemporary values and the accepted order, did not emanate from a vacuum. He is a full-fledged heir to unspeakable regional barbarity, which, in his mind, excuses more.

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2023 by Eric Nilsson