DECEMBER 18, 2021 – Yesterday I got sidetracked by a PBS series about the War of 1812—the “Forgotten War,” more forgotten than the other “Forgotten War,” which, you’ll remember, was the “Korean War.”

Even as an undergraduate history major, I emerged from college without much memory of what’s also called the Second American Revolution, more than two generations before the other Second American Revolution, known as the Civil War.

What I learned from yesterday’s self-directed cram course is that the “fog of war” describes most accurately the War of 1812. For starters: disagreement among historians regarding the casus belli. Ask any “American patriot” about the cause of the Revolutionary War, and you’ll hear, “freedom” or “taxation without representation”; ask what triggered the Civil War, and you’ll be told “slavery” (the Northern answer) or “states’ rights” (the Southern version). Ask about the cause of the War of 1812 (ending in 1815), and you’ll likely witness complete puzzlement.

From there it’s downhill. The conflict—a sideshow of the British war against Napoleon—was a series of military debacles for the U.S. that led ultimately to America’s . . . survival, giving the lie to what my (Daughter of the Pilgrims) grandmother used to say, “Sometimes things go so bad, you can’t win for losing.” The war battered the American economy, and Southerners panicked when the British recruited 4,000 slaves living along Chesapeake Bay. In New England, meanwhile, otherwise respectable Federalists opposed the war so bitterly, they called for . . . secession. Their main concern was the “freedom” to make a buck, which they managed to do behind the scenes by selling stuff to the British—as an American POW in Canada discovered in the packaging of prison rations sourced in New England.

After three-plus years of blood-letting, the victor wasn’t readily evident, though Canada, perhaps, could claim limited victory—for not becoming part of the United States. The losers, however, stood out by disappearing: Indian nations caught in the middle.

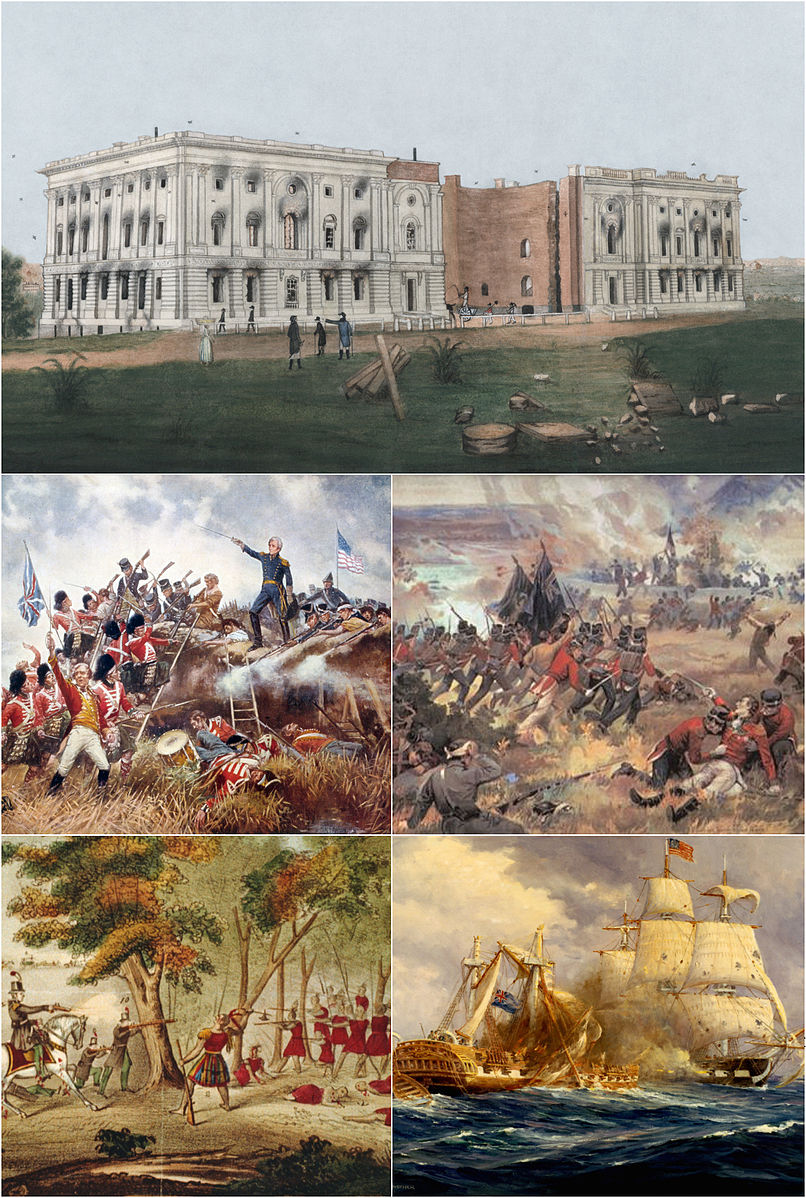

As with any war, savagery—all sides—triumphed. Americans plunged in first, when in York (now Toronto), they torched civilian homes and property and showed no mercy for women and children. The British, of course, returned the favor—on American soil.

From an American perspective, the most disturbing scene was in Washington, the infant capital designed by Frenchman L’Enfant. Dolly Madison had just arranged settings for 40 guests at the White House. The intended guests, however, weren’t the British troops who showed up for dinner a short while later. After busting out wine and feasting in fashion, the “visiting soldiers” torched the place. By comparison, the raucous scene at the Capitol on January 6 looks more like a silly outburst by middle-school brats.

But war was good for something. It gave us a national anthem (though not formally adopted until 1931) and a slogan: “Don’t Give up the Ship!” Except . . . soon after Commander Lawrence said, “Don’t give up the ship!” (and died) everyone aboard . . . gave up the ship.

History: what a wonderful world of myth and mist!

(Remember to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.)

© 2021 by Eric Nilsson