APRIL 13, 2022 – During my days in the capital, which included mass, pro-Solidarity demonstrations that I joined to get a closer look, I learned three things about Poland that would’ve escaped me without on-the-ground exposure.

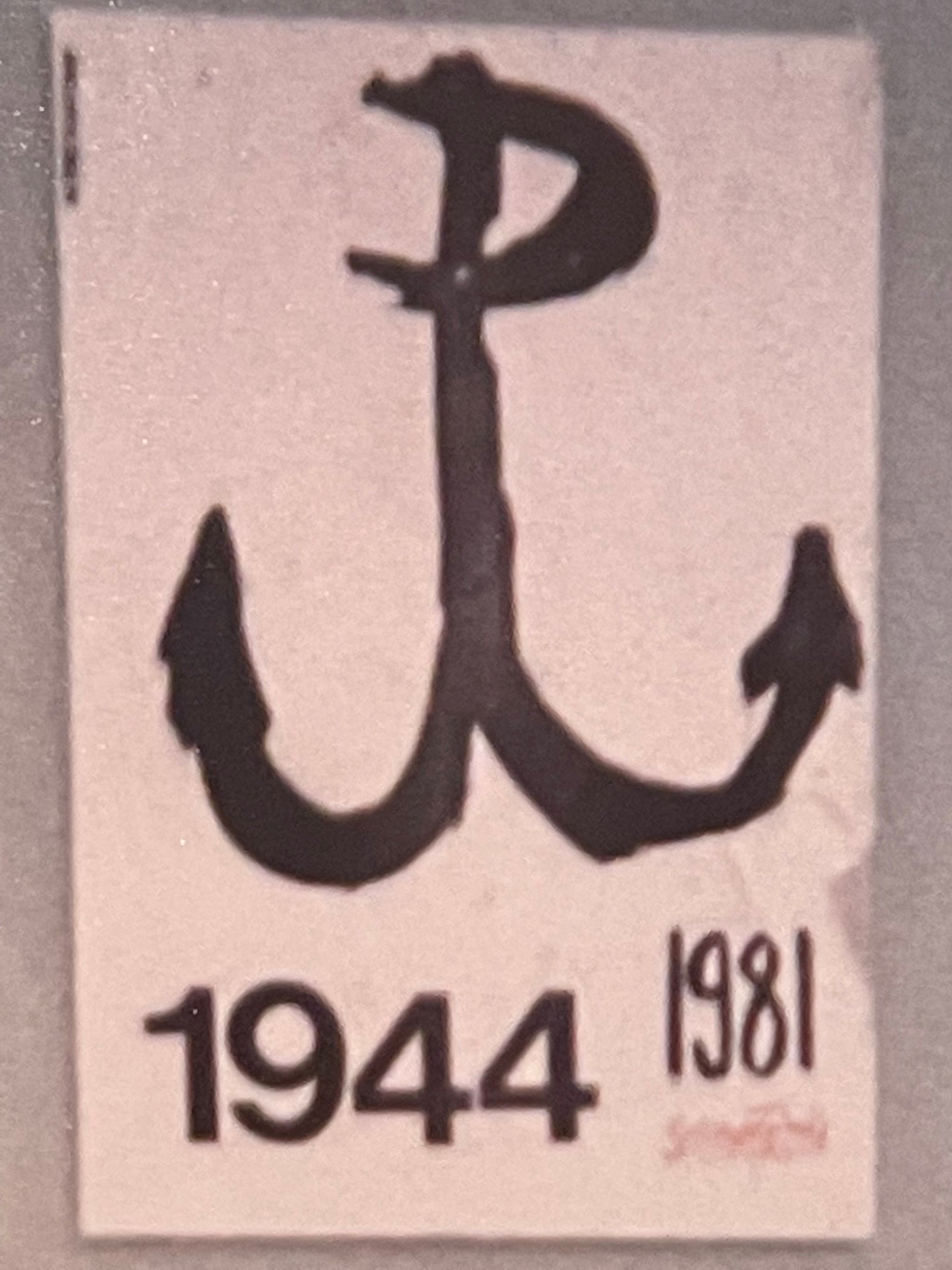

First was the psychological proximity of WW II. For many Americans, that conflict was epitomized by Pearl Harbor, D-Day, the Battle of the Bulge, and the battles for Pacific atolls—all thousands of miles from the American mainland. For Poles, however, the war started with the German Blitzkrieg more than two years before Pearl Harbor—decimating their country long before we broke free of our isolationism. In 1945 the United States celebrated victory, but in the wake of untold death and destruction across Poland, its people continued to suffer, this time by Stalin’s power grab from the east. If Americans of my generation viewed WW II through the distant lens of high school textbooks and Patton-like films, our Polish counterparts saw the uprising of 1981 as vindication for their losses from 1939 forward, first under the Germans, then the Russians. To the Poles, WW II wasn’t a remote conflict. It connected directly to the present, as reflected by the four elements of a poster widely displayed in Warsaw: 1. “1944” (the year of the Warsaw Uprising against the Nazis); 2. A stylized anchor which doubled as the letter “P” (symbol of the Polish Home Army, directed by the non-Communist Polish Government in exile in London during WW II); 3. “1981” (the current year); and 4. The Solidarity logo.

Second was the power of the Catholic church. Based on the ubiquity of the “Polish Pope’s” portrait—inside church grounds and throughout the country—and the Poles’ reverence for him, I concluded that John Paul II, not Premier Brezhnev or General Jaruzelski, was the moral authority of Poland. And unlike Hungary or Czechoslovakia, Poland remained an almost universally observant Catholic society. Irrespective of time of day or day of the week, whenever I poked my head inside a Catholic church in Poland, I found a full house representing a cross-section of society. This powerful institution, which commanded the allegiance of everyone other than elite Communists, formed an invincible bulwark against the regime.

Third, despite staggering personal and property losses in WW II and from the Communist domination that followed, Poles exuded resilience, much of which was grounded in the richness of Polish cultural heritage. On a Sunday I attended an outdoor concert in Łazienki Park—the Central Park of Warsaw. A large crowd—again, a broad spectrum of ages—was gathered in a nicely landscaped section graced by a statue of Chopin composing under a tree of Majorca (the Mediterranean island he frequented). A performer sat at a concert-grade grand piano and played Chopin’s music—of course. Everyone was silently attentive. The crowd was Polish . . . and so was their beloved Chopin. His music—and his admirers’ resilience—proved more enduring than Hitler’s rage and Stalin’s horrors.

(Remember to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.)

© 2022 by Eric Nilsson