APRIL 12, 2022 – Most of my time in Warsaw was spent in Stare Miasto (“Old Town”). This appellation, however, was misleading. In WW II, German bombing had obliterated it. In an inspirational demonstration of resilience after the war, Poland had assigned top priority to the painstaking reconstruction of Stare Miasto—so masterfully executed that until I toured the museum dedicated to the story of reconstruction, I was convinced the buildings were centuries old.

“Old Town” is where I began to learn how tightly Poles integrated their history—and art, theater, music, and literature—with their current political perspective. Chopin, of course, was a national hero, as was Ignace Paderewski, the world-renowned pianist and composer, who became Poland’s first prime minister when in 1919, the country reappeared on the map. But Poles also impressed on me the hero status of their premiere 19th century bards, Adam Mickiewicz (mitz-KAY-vitch)(1798 – 1855) and Julusz Słowacki (swo-VATSKI)(1809 – 1849; almost Chopin’s exact contemporary).

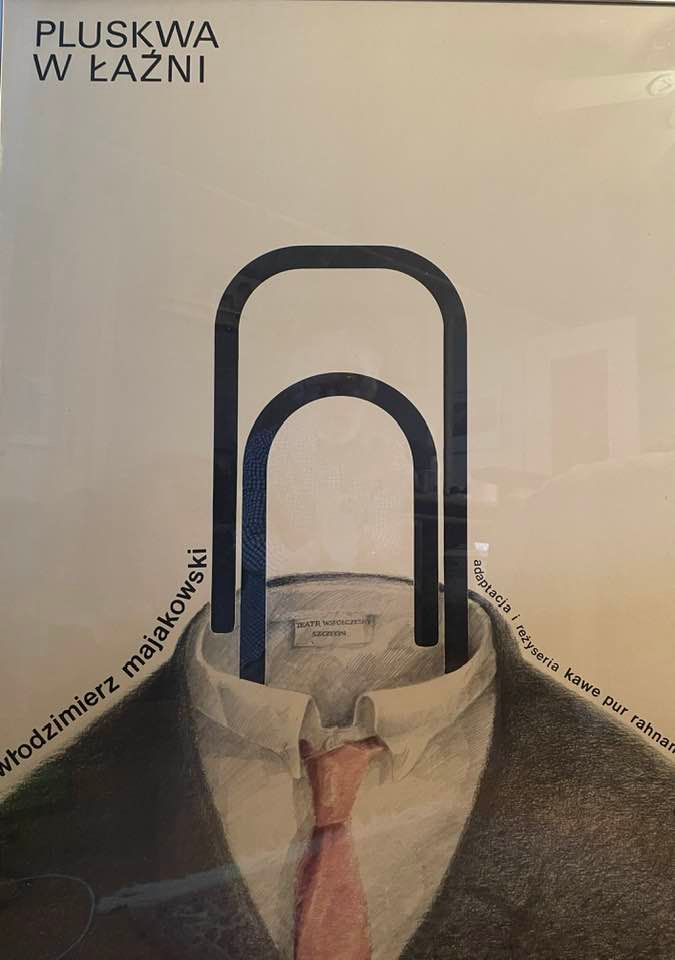

In my Western ignorance, I’d barely heard of Mickiewicz and Słowacki until I entered a poster shop facing Rynek Starego Miasta—the old public marketplace at the center of “Old Town.” I’d been drawn to the shop by the unusual graphic design of several display posters in the window. Inside the small shop was a counter in front of a wall covered with theater posters. To the sole clerk, a patron was selecting—in English—various quantities of the wall-mounted art.

“I’ll take 10 of that one, five of the one below it, six of the one next to that one [and so on],” the English speaker directed. He was a graphic designer from Ireland, and he gave me a quick lesson in the extraordinary art of Polish theater poster design. “In the West,” he told me, “I can get a fortune for these, and here I can buy them for just 10 to 15 złotys [30 to 50 cents] a piece.”

Upon this information, I acquired my own collection. I walked out with 50 posters, some of which—matted and framed—would adorn my bank and law firm offices over the decades that followed. I never “made a fortune” on them, primarily because I couldn’t bear to part with any. Soon after my return to America, an issue of Smithsonian gave cover treatment to the art of Polish theater posters, confirming that I’d stumbled across collector items of the first order.

Apart from their collector value, however, my Polish posters gave me insights into the depth of historical and cultural awareness of the Polish people. Wherever I traveled within the country, people were curious about my selections, and since many of the posters featured familiar plays by playwrights famous to Poles, the posters served as visual aids for many history and cultural lessons. At the head of the class were the works of Mickiewicz and Słowacki, who 140 years before, had captured anti-Russian sentiments of the day. In 1981, the same feelings prevailed—as did the popularity of Mickiewicz and Słowacki—and a contemporary playwright, Karol Józef Wojtyła, better known to the world as Pope John Paul II.

In 1981, the best Polish graphic designers applied their talents to political posters featuring Solidarity. Their work was on public display everywhere I traveled.

(Remember to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.)

© 2022 by Eric Nilsson