MARCH 6, 2024 – (Cont.) As Dan found his stride, his minions fell into line behind him, and we all landed “in the dough” thanks in large part to the Clinton Era economy. My own group was ringing the bell consistently from quarter to quarter. In a public company, however, there’s no rest for the weary: today’s success becomes tomorrow’s floor. I soon felt like the cartoon dog chasing a bone tied to a front-end extender attached to his collar—no matter how fast my division ran, we never caught up with Dan’s ever-increasing expectations.

I remember the day when I was handed our latest pie-in-the-sky budgeted “numbers” for the next quarter. “Impossible!” I grumbled aloud inside my office. But before I got too out of sorts criticizing Dan, who understood little of our division’s business, I pondered the pressure that he, in turn was under to beat the department-wide number for the previous quarter. The source of his burden was his boss. And what about his boss? He took orders from the CEO, and the CEO was given directives (and incentives) by the Board of Directors—who were responding to mutual fund managers who’d bought the bank’s stock—and could just as easily sell it—with consequent up and down impacts on its value. But who was ultimately invested in those mutual funds? Oh yeah, I realized: working stiffs like me with a 401(k). “If the latest statement showed a less than stellar performance for one mutual fund or another,” so said millions of working stiffs across the economy, “sell the mutual fund shares!”

On the heels of that revelatory moment in which I was part of the problem, I sent a brief email to my managers telling them that for the next quarter, they needed to crank up revenue and keep the lid on expenses.

This never-ending routine never abated.

The constant pressure to grow led to pure hocus pocus, which gave me unsettling insight into the stated values in my 401(k). At a biweekly “direct reports” meeting with my peers and me, Dan described a prime case of glaring financial deception. He did so unabashedly, even enthusiastically.

The context one of the constants of his meeting agendae: an updated report on the department’s “Best Practices” performance. For all too long this was a corporate-wide campaign—a little like the never-ending “Get Milk!” ad campaign that ran parallel to “Best Practices.” The latter was a corporate fad; one more aspect of “corporate see, corporate do” behavior that afflicted most organizations in that era.

If the basic idea behind the initiative was valid, in practice it became a parody of itself. Instead of devising better ways of doing things simply because they were better, people were incentivized to submit “ideas” to a whole bureaucracy established to administer them. Ironically, much of the bureaucracy was devoted to handling the “incentives,” mostly in the form of congratulatory paperwork (letters of acknowledgment; certificates) and little pennants designed for display in a worker bee’s office cube. When the incentive approach wore thin, we were given mandates: each month, every division manager was evaluated by the number of “Best Practice” ideas submitted among division employees. To boost underperformance, an actual number was imposed, and over time, just as our financial numbers were under constant upward pressure, so advanced our “Best Practice” quotas.

Dan went all in, just as he did with every hare-brained corporate initiative. At each direct reports meeting he’d review the latest “metrics.” On the line designated, “Average No. Ideas/Person,” the figure was carried out four places to the right of the decimal point.

My group detested the program. Already a maverick, I quietly dropped the “Best Practice” requirement within my division. If individuals wanted to submit an idea so they could “fly a pennant,” I wasn’t going to stop them, but I wasn’t about to clutter up their time talking about—let alone compelling them to come up with—“Best Practices” ideas purely for the sake of filling a quota.

Predictably, my group was always in last place on Dan’s weekly report, for which I received regular reprimands. “This week your people are at zero point 3546 per person,” Dan would say. “I need to see improvement.” For a time, after promising I’d “see what I could do,” I’d submit a bunch of lamo ideas myself. This complete waste of time would increase the average by point one or two and temporarily relieve the pressure. “I’m seeing some improvement month-over-month,” Dan would say, “but you’re still short of goal.”

Ultimately, I gave up, but not before sending in one last “Best Practice” idea—anonymously. Next to the line, “MY BEST PRACTICE IDEA IS:” on the official “Best Practice” idea card (one card per idea), I wrote, “END THE BEST PRACTICE PROGRAM!”

Coincidentally, when my division’s performance numbers dropped on Dan’s next report, he used the occasion to lecture all of my peers and me on the “value” of “Best Practices.”

With an entirely straight face, his speech—nearly verbatim—went like this:

“Here’s why we all need to take Best Practices seriously. On a recent earnings call—you know, with institutional investors, financial analysts, and so on, [the CEO] pointed out the value of Best Practices. He dug down into the metrics to establish the average number of Best Practice ideas per employee per month times the number of corporate employees and the average cost savings or revenue improvement per Best Practice idea. Doing the math, he showed how the program works out to add a dollar and seven cents of value per share.”

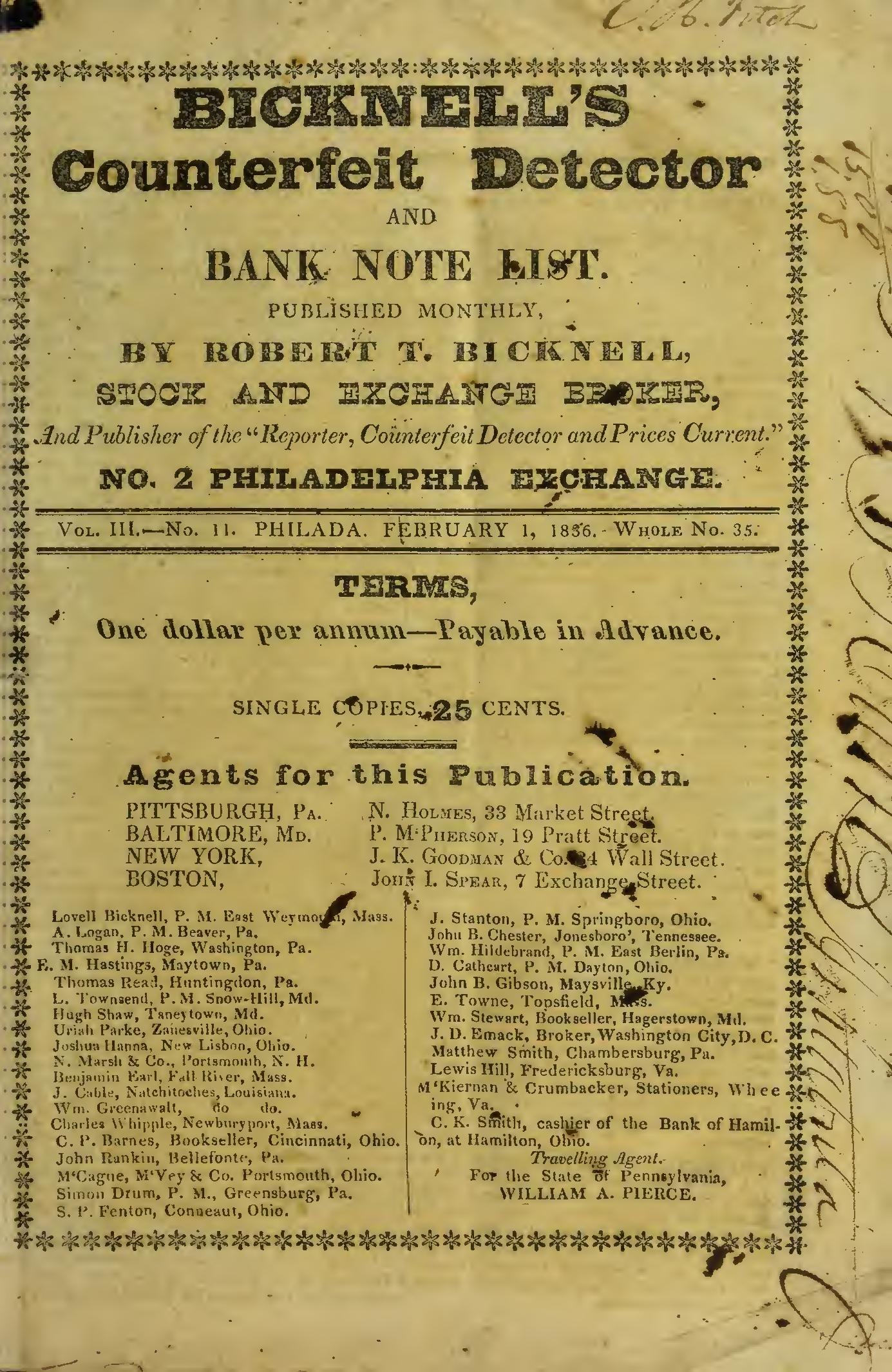

I suppressed my reaction. What Dan had just described with complete conviction was a virtual counterfeit machine.[1] Multiply that across corporate America, and how much of the stock market, I wondered, is based on pure fiction? Maybe my dad’s obsessional warnings (at the time) about the “phony financial system” were based on a grain of truth.[2]

As Dan fed us the corporate line, I found cynical amusement in my unstated proposition: bag the whole stupid “Best Practices” initiative, and the cost savings might well boost the price of bank stock by $2.14 per share—double what the flim-flam artists had apparently told Wall Street the program was worth. (Cont.)

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2024 by Eric Nilsson

[1]At the time I was studying in earnest the largely overlooked but lucrative industry of administering and disbursing settlements in class action securities fraud cases across the country. Much of the fraud (using the term loosely), ironically, was on the part of the very boutique plaintiff law firms that specialized in securities fraud cases. They’d employ someone to monitor the share prices of an array of public companies. Whenever the law firms observed a precipitous decline, they’d fire off a lawsuit claiming fraud on the part of management—why else, went the logic, would a stock price plummet other than because of some form of allegeable fraud? Their fellow specialty firms would do likewise. The four or five firms engaged in the racket would then descend on the court and fight each other for the plum assignment of “lead counsel,” which appointment, in turn, would be tied to the lion’s share of the lucrative fees—almost universally 33% of the eventual settlement (almost none of the suits went to trial). After the usual spate of formal discovery, the targeted company would come to Jesus and see that right or wrong, their own legal fees would burgeon out of control absent settlement. Surrender at a cost of a few million bucks was the only sensible resolution for the defendant company, its directors, and officers (who for additional leverage often got named in the lawsuit). After taking its lion’s share of the loot (settlement funds paid by the defendants), lead counsel would then hire one of about three small accounting firms across the country that specialized in the whole pirate operation. That lucky firm would then send notices to all the record shareholders and administer disbursement of the settlement proceeds (net of the 33% legal fees). It was a regular racket, and I gathered enough data to determine it was about a $30 billion/year industry.[1] Since we were a bank, after all, I figured we could make tons of money purely on the float—interest earned on the settlement funds during the time from when settlement checks issued to the class members were cut/mailed and when they were actually deposited and routed through the Fed back to our bank for payment. Back then, the average float time was 14 days and the annualized interest on the float was running at about 5%. Thus, if we were handling a $10 million settlement fund, my division would earn ($10 million x 5%)/365 x 14. Multiply that by say an initial market share of just 10% of the $30 billion/year “industry,” and the formula would give us ($3 billion x 5%)/365 x 14. I called the prospect “funny money.” A cynical observer could’ve called it a “counterfeit operation.” Given the enormous processing capacity of our corporate trust department, I figured we could develop a sub-capacity for class action settlement administration that would be far more efficient (and far less costly) than the current crop of small accounting firm-administrators. In fact, we could provide the administration services for free provided we could hold the funds and “earn the float.” We had just launched the business when I got fired—but I’m getting ahead of myself.

[2]Two decades earlier my dad had found himself on an arch-conservative mailing list, which led to subscriptions to several economic doomsday newsletters. Generally skeptical of hawkers and salesmen, he fell prey to the time-honored fear-mongering used by charlatans. “The sky is falling!” their newsletters proclaimed, “which is why you need to (a) renew your prescription to our newsletter, which will give you continued updates on the falling sky, and (b) buy gold, guns, and garlic from our advertisers to protect yourself and your family when the sky does, in fact, fall.”