MARCH 1, 2024 – (Cont.) One of the most bizarre experiences I had during my corporate life was the ignoble departure of the guy who’d hired me. Hmmm . . . one sentence into the story and I’m getting way ahead of myself.

When I first met Keith [a made-up name to protect him and me], he impressed me, mostly because he wasn’t nearly as conservative as my lawyer colleagues. By “conservative” I don’t mean politically speaking; I mean being risk averse. Most business lawyers are trained, and for the most part, paid to identify, then mitigate risk. The better they are at this combination in both expertise and volume of work, the more they get paid. Corporate P&L (profit and loss) managers and executives, on the other hand, are incentivized to maximize profit—revenues minus expenses—wherein risk plays a very different role: the greater the risk, the greater the reward, provided the risk-taker doesn’t blow things up in the process.

Keith was very much a risk-taker, and by having done so during the couple of years that he was at the helm of his corporate fiefdom, he’d grown the business (corporate trust) considerably. In sheer dollar if not percentage terms, profitability followed. He was impressively entrepreneurial, and true entrepreneurs are inherently geared for risk-taking.

In addition to being a risk-taker in business, Keith exuded the trait on a personal level. His education and vocational background prior to being placed in charge of corporate trust was all about industrial psychology and human resources. He had no finance background whatsoever and no previous exposure to the arcane world of corporate trust.[1] Yet he talked as if he were very much in his element. This impressed me—that he would plunge into largely unknown waters and figure out quickly not only how to stay afloat but how to swim competitively.

Consistent with his risk-taking were his gregarious personality and sense of humor, and these traits too I admired. We hit it off well from the very outset of my interview lunch in the bank’s private dining room, and the comp package he offered was a step up from the law firm. I was ready for a new venture in a new setting, and I didn’t need long to accept the offer—and forget all about not making partner at Oppenheim Wolff & Donnelly.[2]

For me the transition from law firm to bank was a change far greater than their geographic proximity to each other (just two blocks in downtown Minneapolis). Everything from lingo to personnel to various corporate protocols to the very work itself was new. For the first time in my career I was directly responsible for a “P&L” group, for a “bottom line.” Keith was patient enough, but I was nonetheless eager to provide evidence that he hadn’t made a mistake in hiring me. Within a couple of weeks, I had my chance.

The kick-off for the bank’s annual United Way campaign was in the final planning stages. For the big event, the people in charge had secured the main auditorium of Orchestra Hall a few blocks down Nicollet Mall from the bank. The C-suite executives had “volunteered” to stage a comedic skit, which would involve the bank’s CFO scratching away on his violin, followed by an actual violinist not scratching away on a violin. But where would the execs find “an actual violinist”?

Somehow word had circulated that I played violin, and one day I received a call from [Thomas Stanley] the bank’s general counsel seeking confirmation of the rumor When I affirmed, he said he needed “to discuss something of vital importance” and asked if I had time to come up to his office.

“Sure,” I said, having no clue what I would be signing up for.

While I waited for the “up” elevator, Keith appeared and hit the “down” button. “Where ya headed?” he asked cheerfully.

“General counsel’s office,” I said.

“Really? What’s going on?” Keith’s tone signaled curiosity tinged with concern. “Something I should know about?”

“I have no idea,” I said, as the “up” elevator dinged. When the doors opened and I stepped aboard, I managed to add, “I was simply told it’s of vital importance . . . I’ll let you know, Keith.” I left him behind with furrowed brow.

I’d never met the general counsel before. He was an older gentleman, adequately cordial and with the countenance of someone who took things seriously. He offered me a chair inside his office and closed the door. I then learned in excruciating detail every aspect of the “skit.”

Conveniently, the sketch was intended to be comedic. I say “conveniently,” because I couldn’t suppress my laughter—not at the slapstick play but at the very scene in which I was in the moment playing a role. There before me was the top dog lawyer of the bank describing in the most serious manner possible a ridiculously amateurish skit devised for production in front of a large crowd of bank employees—in Orchestra Hall, no less. Mr. Stanley looked pleased not offended by my laughter, not realizing that I was amused by him, not the skit.

The meeting lasted at least a half hour as he considered numerous alternatives to every detail of the plan—including what I as the “actual violinist” would play.

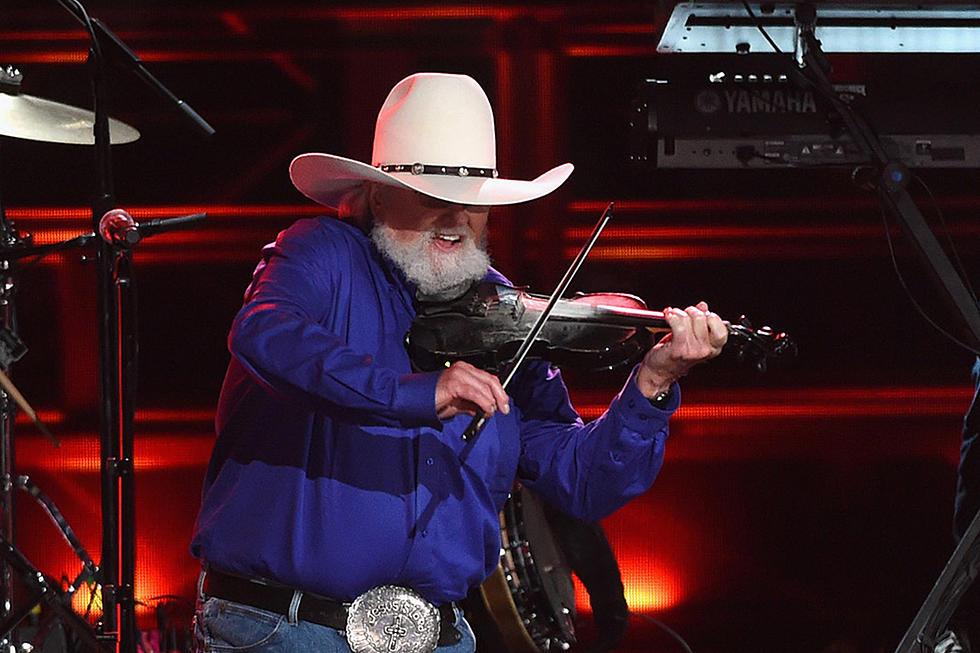

“I was thinking ‘The Devil Goes down to Georgia,’” he said. “Can you play that?”

“Uh, I’d rather not,” I said. I didn’t want to reveal that I had no idea how to play the song that made Charlie Daniels famous—and I wasn’t about to try. “I’m more of a classical violinist.”

“Maybe something by . . . Vivaldi then?”

I was heartened by his invocation of an actual composer. “That would be better,” I said.

He returned to staging issues. After exhausting the possibilities, he allowed me to take my leave—with the understanding that I’d be open and available to discuss further refinements. As he accompanied me to the elevator, he leaned into me and said in a low voice, “By the way it would be good to keep all this under wraps for the time being. We want it to be a surprise for everyone. So top secret, okay?”

“You got it,” I said.

Within 10 minutes after I returned to my office, Keith was at my desk. “What did [Tom] have to say?”

“Sorry, Keith,” I said, “I’ve been sworn to secrecy.” I wanted to ask Keith if he had a reason to worry. Was he keeping something from me? Was he worried that something in my division had gone awry that wouldn’t eventually work to Keith’s detriment?

* * *

About a week later, after several intervening phone calls, Thomas Stanley came down to my office to discuss his latest ideas. Keith happened to walk by. After the chief lawyer had departed, Keith returned to my office. His curiosity had gotten the best of him—to the point of his being miffed at having been left out of the loop.

“So what on earth is going on?” Keith asked.

“He wants to consult with me on something he’s working on,” is all that I allowed.

“Really? He’s got all those lawyers up there, and he’s consulting with you?”

“That’s right, Keith. I wish I could tell you more, but I can’t. It has nothing to do with corporate trust—just something about which I’ve got some special expertise.”[3]

“Wow. I’m impressed. Makes me look good—hiring a lawyer who’s smarter than any of the lawyers in the law department.” He wasn’t kidding.

Nor was he kidding the first—or umpteenth—time I heard him pontificate about one thing or another in the privacy of his office as he paced back and forth, then look out the window as he tugged on waist of his trousers up and said, “You know, Eric, sometimes I just can’t believe how smart I am.”

The more he repeated that self-assessment the more I doubted he was even half as smart as he thought he was. (Cont.)

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2024 by Eric Nilsson

[1] As I recall in his previous position he’d worked in HR and was the point-person for personnel matters associated with the corporate trust department. He was familiar with the people but his understanding of the finer points of the business was relatively limited.

[2] The firm gave me a royal send-off—a full department party (at which by popular demand I performed one last show of impressions of everyone’s gait) garnished with hors d’oeuvres and desserts crowding a large conference room table and lubricated with a full complement of beverages. In reflection of even greater good will, the firm paid me my full year-end bonus. (Granted, people understood that I was moving into a role that could generate lucrative fees for the firm, so there was certainly an incentive to “be nice.”)

[3] On cue I wound up playing a few phrases from the movement of an accompanied Bach partita. The “gig” as it were allowed me to say I’d performed “on stage at Orchestra Hall.”