JANUARY 29, 2024 – (Cont.) My case-in-chief took a day. For the rest of the week, the defense fired a Gatling gun of spitballs into the courtroom. I had to bite my tongue on my principal objections to the lawyer’s unorganized evidence: lack of foundation and irrelevance.

In a trial, you always have to be thinking about the record on appeal—by either side. If critically prejudicial, inadmissible evidence (e.g. hearsay; testimony or exhibits lacking foundation; relevance) lands in the trial transcript, you can’t object to it on appeal. On the other hand, you also have to be cautious about objecting. The lawyer who objects to all inadmissible evidence risks the impression that there’s something “to hide”; that the objecting lawyer is trying desperately to prevent the jury from seeing, hearing “the other side to the story.” Over-kill on objections can annoy the jury.

In any event, I was amazed by the other lawyer’s bumbling. For a roadmap to his witness examinations he used scratchings on page after page of a legal pad, and he seemed never to have the pages flipped to the right one. His questioning was halting, replete with, “Uhs” and “Ums,” as if the Gatling gun had a bad case of irregular mechanical hiccups. I had all I could do to maintain what I thought was the optimal “countenance”—an attentive poker face; on the one hand, no smirking, but on the other, no furrowed brow signaling that I was at all concerned by the evidence he was putting in.

As the trial unfolded, I recalled my initial meeting with my client’s senior management team: Was I mean enough? Were my fangs sharp enough? Did I have the resources to fight to the mat? Here now playing out in the courtroom was what I believed was the definitive answer, and I was relieved that at least one, sometimes two senior bankers were in attendance for every minute of the trial. They could see and hear with their own eyes and ears how things were going. They could report back to the executive suite on my performance—and my opponent’s floundering—and I was confident that finally, finally, I had ”arrived” in my nearly 30 self-doubting years of practicing law. I was now a bona fide . . . lawyer.

But I misread, misjudged those two most important banker-witnesses—witnesses to my performance, not witnesses who ever took the stand. During the recess after closing arguments, I asked the two bankers confidently, “So, over all, what did you think?”

I was hoping for a vote of confidence. I was shocked when I heard the answer.

“I think the other lawyer was a genius,” said the bank’s chief credit officer, who’d been present for much of the trial.

“Huh?!” I said, unable to hide my disbelief.

“To gain sympathy with the jury,” he said, “the lawyer tried to look really, really bad compared to you, and he succeeded. I’m not optimistic about how the jury is gonna come out on this. They’re gonna feel way too sorry for that sly bastard.”

As things turned out, the jury returned a self-contradictory special verdict form that confused the judge and us lawyers. Since it was well past five on a Friday afternoon, the judge informed us that he wanted to arrange for a conference call first thing the following Monday . . . then struck his gavel.

The case went downhill from there in the weeks that followed and landed in a heap of mush of motions, orders, motions to reconsider, and . . . cross-appeals. Understandably frustrated, senior management team at the bank decided to retain a “high-powered” firm to take on the appeal work. Their choice? The very firm where I’d begun my career. The lead lawyer, a veritable junkyard dog, had been in first grade (no doubt raising Cain) when I was in high school. I welcomed him to the fray, and he graciously thanked me for my assistance in transitioning the matter to him. After reviewing the trial transcript, he had nothing but bare-fanged contempt for judge and jury. I’d experienced extreme relief in being relieved of my burden.

The last I heard of the case—well into the following year—it had become an interminable tar baby reminiscent of Bleak House by Charles Dickens,.

More than a decade passed. Then came a day in December 2023 when my wife said out of the blue, “Why don’t you take [our eight-year-old granddaughter who was on hand] and go down to the lot by the grocery store and buy a Christmas tree; not a big one but one we can put on top of the table-trunk in front of the window in the sitting room?” (See 12/__/23 post)

Minutes later I’d found the perfect tree. In handing my credit card to the guy in charge, I made small talk about my own “tree garden” up at the lake and the threat to white pine saplings posed by deer browsing in winter. The guy was ruff around the edges—and very opinionated.

“Where’s your trees?” he asked. He reeked of cigarettes.

“Up near Hayward,” I said.

“The deer population is way down there,” he said authoritatively.

“Not in our immediate area,” I said, based on firsthand knowledge.

“Yes they are,” he said, defiantly. “They’re down—way down—all over. Bad winter last year wiped them out.”

“It was a pretty tough winter, I’ll grant you that,” I said, as he handed back my credit card. As I picked up my tree I asked, “Do you have any loose boughs I could have?”

“Yeah, over their in the tub,” he said, “10 bucks a bunch.”

“I think I’ll pass,” I said. On the short drive home I pondered the likelihood that the Christmas tree guy had scoffed at the Biden/Harris sticker on the back window of my wife’s Rav4.

A week later I found myself searching our latest Visa card charges to track down a recent telecom charge. In scrolling through the list I happened to see the name of the defendant in my “Last Trial.” Sure enough, he and the guy from whom I’d purchased our Fraser fir at the grocery store lot were one and the same. Amazingly, he was still in business. If I’d failed to recognize him, surely he hadn’t recognized me. Good thing, too.

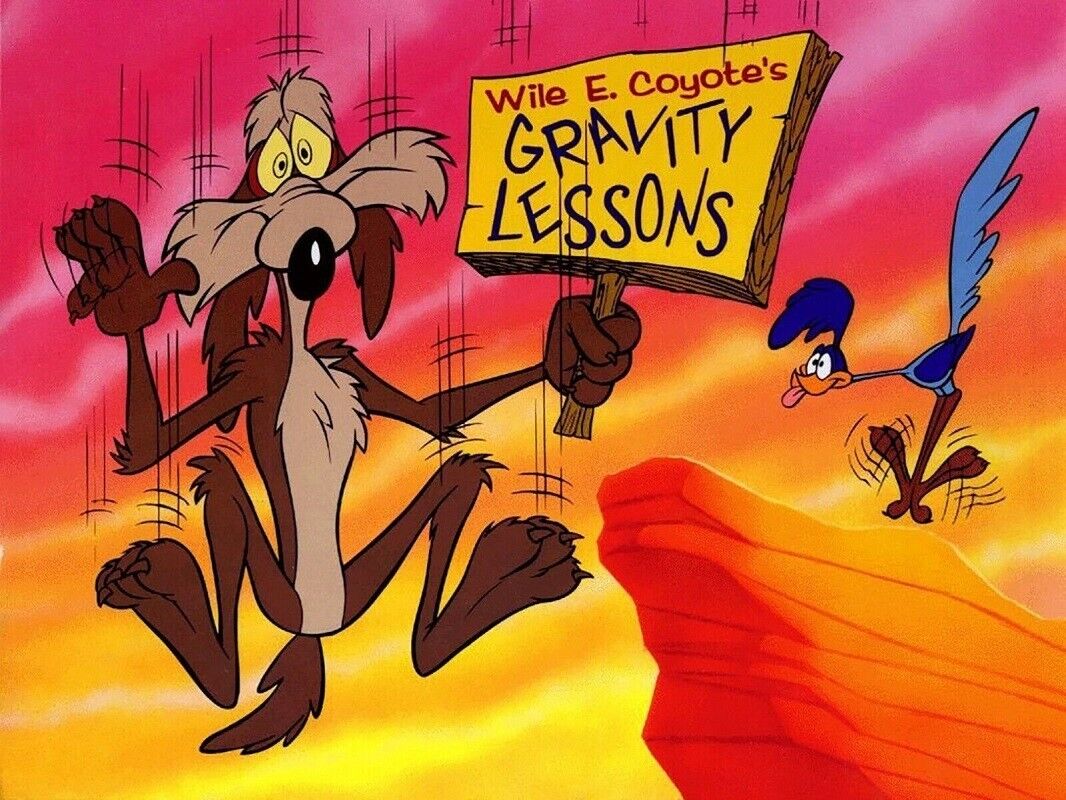

I now saw my Last Trial in perspective: I’d definitely played the role of Wile E. Coyote.

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2024 by Eric Nilsson