FEBRUARY 9, 2024 – (Cont.) I remind the reader that embedded in my murder case is supreme irony. Except . . . to appreciate the full scope of the irony you have to understand the improbable background to the story, only a portion of which has yet been told. Moreover, by now telling the tale in full measure, I’ve stumbled upon a latent compression of ironies unbeknownst to me until just now, to-wit:

In researching that recording of Horowitz’s comeback recital, I made a most astonishing discovery: my good friend Greg Schatten had been flat out wrong. Greg the Wunderkind, the piano prodigy, whose genius was universally recognized by his peers, the school faculty, Juilliard—where he studied after Interlochen—and the audiences who’d heard him perform, had been wrong about Horowitz’s mistake, about the master’s “double-flub” before launching successfully into that sensational comeback recital in Carnegie Hall.

Thanks to YouTube, I found the live recording of the famous recital. The posted performance included a rolling score of each piece. I was thus able to read the music to the Bach Toccata in C that Horowitz played to open the concert. The “mistake” in the opening statement wasn’t a mishap at all. What Greg heard, what I heard—repeatedly—was an extra note intentionally inserted by the hand of J.S. Bach himself. It sounds like a grace note, an errant grace note[1], but it is very clearly notated and thus, correctly played by the performer—in the case at hand, by Horowitz. Thus, my “blue book story,” as it turns out, was based entirely on a misapprehension of fact. The “double-flub” was none but my own, instigated by a prodigy, no less, in my lame attempt to launch my alternate career as a writer.

What drives the irony of my story even deeper is the effect that the F inside my blue book would have on my GPA and class rank—and how that unwelcome result would one day become inverted at a critical moment.

As my law school days drew to a close, however, that F was the gaping hole below the waterline of my psychological ship. While my classmates—confident they’d pass the bar exam after graduation—were lining up interviews with an array of law firms and public sector offices, I was ready to abandon a listing vessel. I figured my prospects for a law job were irretrievably non-existent. Besides, how would I ever like practicing law?

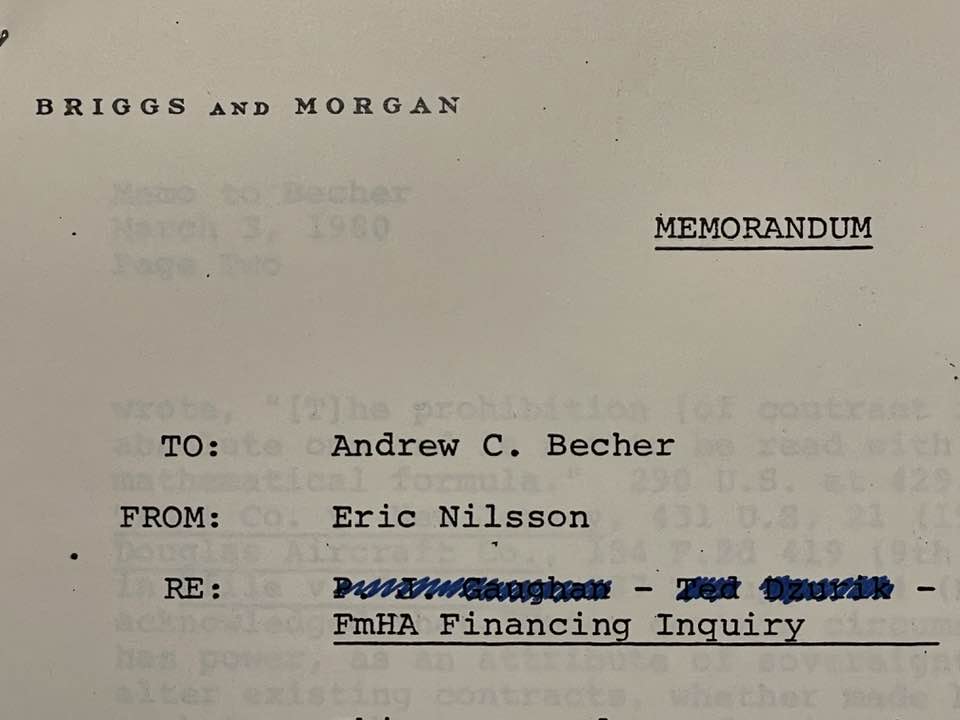

Yet, incongruously, during that last year of law school I went to work every day as a clerk at the prestigious St. Paul firm of Briggs & Morgan, where, thanks to a connection my dad had there, I’d previously worked as a messenger. The messenger job required no special academic aptitude; just the ability to drive in opposite directions simultaneously, as lawyers with competing demands called at once, demanding that their letters and documents be delivered immediately.

At the outset of my last year of school, my dad had started hounding me to “get some applicable experience.” To placate him but also to procure my own source of funds, I responded to a posting on the school job board for an open law clerk position at Briggs & Morgan. Since I’d gotten to know a number of lawyers there during my messenger days, I figured I’d apply.

Curiously, the hiring lawyer—Jack Kenefick of the litigation department—didn’t ask about my grades. At the time, the big F in insurance law lay ahead of me, but my performance thus far had been a long way from stellar. Jack knew me—not well, but we’d gotten somewhat acquainted during my year as a messenger—and on the basis of that familiarity, a casual “interview,” and a couple of writing samples, I got the job.

My office, as it were, was a glorified shelf in front of a window squeezed between two floor-to-ceiling bookcases in the firm library on the 25th floor of the art deco First National Bank Building. For my architectural edification, I had a grand view of the state capitol, Cass Gilbert’s masterpiece standing proudly just north of downtown.

My job was to respond to research requests by firm attorneys. They’d dictate background and issues into a memo, which would be forwarded up to the library. Sometimes the requesting lawyer would want to chat about the context of the assignment. I’d then put my research skills—such as they were—to work, combing through annotated statutes, digests, and other entry sources and scour volumes upon volumes of reported appellate cases and updates. Once I’d cobbled together an analysis, I’d write out—in cursive on a legal pad—a memorandum, which I’d give to the requesting lawyer’s secretary to type up. Once I’d revised and proofed it, the memo would be submitted.

The clerkship had everything to do with research and writing but absolutely nothing to do with the actual practice of law. I enjoyed the puzzle aspect—searching statutes and case law and engaging in often tortuous analyses—and loved the writing side. I went out of my way to engage with attorneys and staff, and found much to talk about. Many lawyers had recently jumped onto the long-distance running wagon, which was accelerating at breakneck speed. This phenomenon sparked frequent conversation, and my competitive success in road races and marathons elevated my stock among the running crowd at the firm.

I’d also developed a somewhat dubious reputation for pantomime and gait-imitation. I’d discovered this quirky ability at Interlochen and quite by chance—mimicking fellow students one evening, one kid after another as they entered the dorm just ahead of curfew. Within minutes I found myself in the spotlight of an impromptu theater (the dorm lobby), surrounded by growing laughter, as each subject of imitation joined the crowd of onlookers. At Briggs & Morgan, I gradually established a repertoire, much to the amusement of attorneys and staff up and down the floors of the firm.

My stint as a law clerk was designed to conclude with the end of the academic year. By that juncture I had barely managed to keep my nostrils above the waterline. I’d be allowed to graduate, and I knew that I’d have to stay afloat thereafter just long enough to study for the bar exam and take the damn thing later that summer. If I didn’t sit for it then, the odds of my ever taking the bar exam would plunge to zero. But after the test? I had no idea what I would be doing, but I was certain it wouldn’t be practicing law. (By default it would be working for my grandfather’s fading business out in New Jersey. (See my Inheritance series (6/23 – 8/23) on this blog site)). (Cont.)

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2024 by Eric Nilsson

[1] Bach inserted these quirks passim throughout his enormous collection of works. You’ll be playing along and out of the blue a strange note will pop out—reminding performer and attentive listener that Bach was way ahead of the rest of the Baroque pack. Greg should’ve known this; he’d certainly studied his share of Bach, but apparently not that particular toccata. My good friend was attracted more to the works of Beethoven and later composers of the Romantic era. We’d played some chamber music at Interlochen, and he agreed to accompany me on my senior recital—the Franck Sonata, which is a royal bear for the piano. Greg not only played it flawlessly, but in our marathon practice sessions, he gave me musical insights and instruction that went far beyond what my own violin teacher could ever provide. As a high school freshman (the year before I transferred to Interlochen), Greg performed Chopin’s Concerto No. 1 in e minor with the Interlochen Arts Academy Orchestra in front of a sell-out crowd in the great hall of the Atlanta Symphony. Sadly, I lost touch with him after Interlochen. What everyone thought would be a glorious concertizing career for Greg never panned out. Rumor had it that early on at Juilliard he suffered a debilitating repetitive injury to his hands. An online search 20 years ago revealed nothing of his whereabouts or even his existence. All that I learned was that his older brother, “Sammy,” who was apparently the family’s “golden child” (Greg used to joke fairly regularly and rather bitterly that in his parents’ eyes, “Sammy could do no wrong”), and like their father, had become a surgeon, had died rather young.

1 Comment

Can’t wait for next few episodes!

Comments are closed.