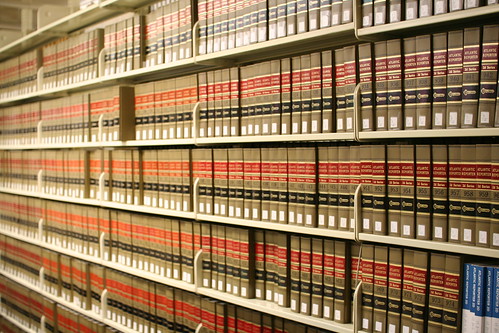

FEBRUARY 14, 2024 -(Cont.) Interpretation of the statutory language was a simple example of the role that case law—“judge-made” law—plays in Anglo-American jurisprudence. Filling the shelves of every law library back in 1983 were thousands of volumes of case law “reporters”; thick, handsomely bound volumes filled with case decisions by state appellate courts and federal district and appellate (including SCOTUS) courts. To avoid having to spend 10,000 years combing through numberless cases, I started with MSA (“Minnesota Statutes Annotated”) containing the entire body of “state legislated law” and synopses and citations of cases that in turn cited the statute pertinent to my case. I then jotted down those citations and tracked down the corresponding volumes from the rows upon rows of shelves bearing case reporters—all arranged chronologically by jurisdiction. Today the contents of all those law books are accessible online (for a handsome fee).

From the beginning of time the whole case reporting system was organized systematically to allow efficient research of cases from one end of the country to the other.[1] This vast ever-expanding body of case law divides between “mandatory” and “persuasive” authority. The former encompasses court decisions with holdings (precedent) that must be followed. Mandatory authority emanates from appellate courts that would have subject matter jurisdiction over the matter under consideration.

Persuasive authority, on the other hand, is case law from outside the jurisdiction. In the absence of or to supplement applicable mandatory authority, a court may look to case law in other jurisdictions but only for guidance.[2]

Often there exists no “mandatory” case that addresses the exact fact pattern of the dispute under analysis. You have to stitch together several—sometimes more—cases to render an argumentative glove that fits the unique facts of the hand you’ve been dealt. In the glove-making, you have to think not only conceptually, analytically, but by layered analogy.

The key concept in my lawsuit was causation. The extant Minnesota cases interpreting the pertinent statutory language were explicit: for no-fault coverage to apply, the maintenance or use of a motor vehicle had to be causally related to the injury but not necessarily the proximate cause. This sort of distinction is what keeps hair-splitting lawyers in business.

I culled through all the Minnesota cases that split hairs between circumstances where no-fault insurance coverage applied and where it didn’t. It was a grueling exercise. For example, in one seminal case, the Minnesota Supreme Court held in favor of a man who in the process of entering (not “alighting from”) the passenger side of a pickup truck stepped on a downed power line as he grabbed the outside door handle. In another case, however, the same court gave the thumbs down to a child who was severely burned when playing with matches while she was sitting inside a car.

After nailing down my analysis, argument, and confidence, I suggested to Brian that the case was worth a shot at “summary judgment.” The procedure works definitively only in instances where there is “no genuine dispute as to a material fact”; where the case comes down to the application of law, not a decision about “competing” facts. But Anglo-American jurisprudence is brilliantly nuanced in the same way the English language is: what’s a “genuine dispute” and what’s “a material fact”? The easiest and most frequent method of defending against summary judgment is to call the judge’s attention to “all the discovery that has been undertaken or yet to be developed” and that immersed throughout all the complicated (and therefore implicitly material) facts is “genuine dispute.” All too often judges—especially indecisive ones—use this “crutch on a silver platter” to deny a motion for summary judgment.

In my case, however, the facts were straight forward. They were embedded in the certified record of the Canadian criminal case in which the armed robber was convicted. That left the law, a perfect case for summary judgment.

I sued out the case. A week later an attorney surfaced representing the insurance company: one Eric Magnuson of the Rider – Bennett firm in Minneapolis. I knew nothing of Eric Magnuson, except that his full name reflected Swedish heritage. When I asked around in our department I soon learned that Herr Magnuson was an established and well-regarded insurance defense attorney and partner of the Twin Cities’ pre-eminent insurance defense firm. Surely my opponent was not someone who’d flunked a law school course on insurance. In fact, years later he would be appointed Chief Justice of the Minnesota Supreme Court.[3]

I began to second-guess myself—for the thousandth time since my first day on the job. (Cont.)

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2024 by Eric Nilsson

[1] It was called the “key system,” proprietary to the West Publishing Company, the main facility and headquarters of which were right down the street from Briggs & Morgan until West’s later move to suburban Eagan, Minnesota. With the notable exception of Lawyers Publishing, which would later play a role in this chapter of War Stories, West held all but a national monopoly of law book publishing, making its owners, the Cafesjian and Opperman families, billionaires. They cashed out by selling the private concern to Thompson-Reuters, a Canadian conglomerate. I would later meet at Dwight Opperman at a social function at his home. He was the company chairman and looked a lot like Colonel Saunders of Kentucky Fried Chicken. I’d also spend the better part of a morning visiting with—or rather, listening to the voluable pontifications—of his son Vance, who’d taken over the role of CEO just before the sale to Thompson-Reuters. The latter was by way of an entrée provided by a friend of mine, John Lindstrom, Opperman’s chief aide, formerly a litigator at Briggs & Morgan. An accomplished trumpet player and very much a Swedophile, John and I had regaled our Briggs colleagues with Swedish Christmas carols at a Monday morning breakfast meeting one December. (When John told me he was taking his family to Sweden on vacation, I asked if their itinerary included any surrounding countries. “No,” he answered firmly. “Why would we want to do that? Sweden is the only country worth seeing.” I gave him a pass on that one—he was a master wood-worker, and I much admired his furniture, especially. In a previous life he’d been a small town cop. He told me that for “kicks” he and his buddies from surrounding farm towns would often use their squad cars—lights blazing, sirens blaring—to hold noontime “drag races” out on country roads.

[2] Case law splits further between “holdings” (i.e. statements of law in direct support of a court’s decision that establish a binding precedent) and “dicta” (i.e. statements that are a court’s commentary, non-essential to the decision and therefore, not a binding precedent).

[3] Of course, I never asked Eric Magnuson about his law school GPA or class standing. When I was in law school, a joke circulated that the A-students became law professors, the B-students become judges, and the C-students became the best practicing attorneys. The joke originated with a C-student preparing for a job interview at a law firm, though as I recall it was based on the rumor that one of our most highly professors, who’d been a straight-A student in law school and was by our time a nationally recognized expert in his area, had flunked out of his job as a practicing attorney and turned to teaching, where he excelled.