FEBRUARY 13, 2024 – (Cont.) Fast forward to a day several months later. The time was close to noon, and most of the other lawyers in the litigation department had vacated for lunch or the athletic club. I was finishing up on something before I myself would head for the club a block away to change and go for my mid-day power run down along the river.

A lawyer from the tax department way upstairs silently appeared in my doorway: Brian Belisle, several years ahead of me, was reserved but cordial and well-liked. He’d not been a recipient of any of my postcards from around the world, however. We’d barely met, but I knew his name.

“You’re the only one around,” he said.

“Yeah, just finishing up some stuff, then I’m outta here too to go run.”

“I don’t want to keep you, but how much do you know about insurance law?”

I gulped. “Just enough to be horribly dangerous,” I said, attempting a shoestring catch.

Brian laughed. “Well, that sounds like more than I know,” he said.

“Not sure about that . . . So what have you got?”

“It’s quite a story,” said Brian.

“I like stories—good ones anyway.” As a beginner lawyer deathly afraid of the shadow cast by my lack of experience, I’d adapted by pretending otherwise. “Have a chair,” I said.

Brian proceeded to explain . . . the murder.

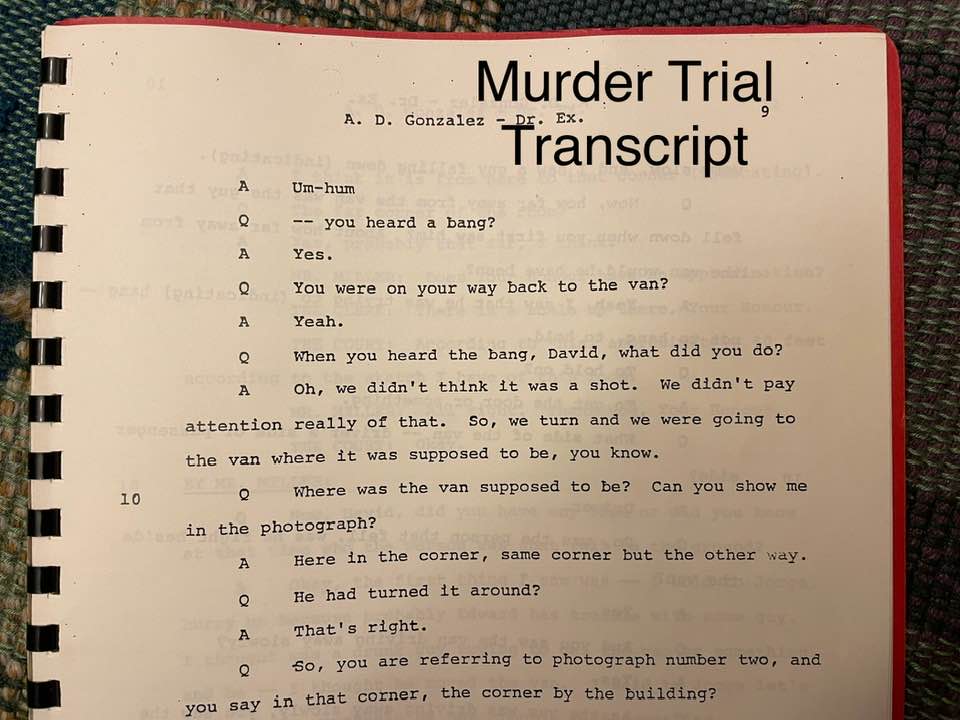

The 30-year-old daughter of a firm business owner client had been recently widowed. Her late husband was a member of a Mexican band from West St. Paul (home to a burgeoning Mexican immigrant community). The band had a gig scheduled for Winnipeg, Manitoba and had driven together in the decedent’s van. Along the Pembina Highway just outside Winnipeg, the group decided to stop at a liquor store adjacent to the Montcalm Hotel to pick up some beer. Everyone except the decedent, who was driving, hopped out to make the acquisition. “Our guy” told his band buddies that he’d reposition the van by the front door of the store so as to make their departure more efficient—they were running a bit late.

And so he did, making a simple circle, then with the van still in gear, rolling ever so slowly up to the front. Unbeknownst to him, however, his fellow band members had stumbled into an armed robbery in progress. The gunman was waving a large handgun in the air and shouting at customers and employees to stay on the ground—all except the cashier, whom the robber ordered to fill a bag with cash from the register. The bad guy then fled.

Not having much of a plan, however, the robber realized that his get-away vehicle was our guy’s van—engine running and transmission in gear. He ran around to the driver’s side, opened the door, and shot our guy point-blank. The murderer then pulled the mortally wounded man out of the van, dropped the bag of cash, retrieved it, hopped into the van and drove off. He went on to commit a string of armed robberies across western Canada before being apprehended two weeks later and subsequently charged, convicted, and sentenced to the slammer.

“The question all this raises,” said Brian, “is whether our client is entitled to death benefits under her husband’s no-fault auto insurance policy. So far the insurance company has denied our claim. The only choices now are drop it or sue.”

“I’ll have to look into it,” I said, utterly clueless.

“I’ll leave it in your good hands,” said Brian, “and let you go run. When you have time, let me know what you think. If you decide it’s worth a shot, I’ll let you handle it.”

As I ran along the noontime runners’ route on the south side of the Mississippi just below downtown St. Paul, I pondered the layers of irony embedded in the matter Brian had referred to me. Amidst the multiple ironies was one newly exposed: in the insurance law course I’d flunked, The Walrus hadn’t spent a minute on Minnesota’s relatively new no-fault insurance statute. My only exposure to it had been in Professor Steenson’s first-year torts class. Lost in time and space was anything of substance from his lectures (I can’t remember that he posed a single question to a single student the entire semester). I do remember Steenson handing out photo-copies of the statute, which served as a “read-along” script for a lecture. Beyond that horrifically boring exercise, nothing else registered. I hadn’t flunked torts. In fact, I’d done fairly well on the exam, actually, which hadn’t included anything about no-fault auto insurance.[1]

* * *

The basic question that I had to grapple with in evaluating our client’s claim under the policy covering her deceased husband’s van was whether his death had arisen from “the maintenance or use of a motor vehicle.” That was the pertinent statutory language on which the case would turn. But what constituted “maintenance or use of a motor vehicle”? The only guidance provided by the statute was largely circular:

“Maintenance or use of a motor vehicle” means maintenance or use of a motor vehicle as a vehicle, including, incident to its maintenance or use as a vehicle, occupying, entering into and alighting from it.[2]

That wasn’t much of a map or compass. (Cont.)

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2024 by Eric Nilsson

[1] Apart from my having stayed awake most of the time, the hallmark of Professor Steenson’s class was Ray Peterson’s having “volunteered” me to oppose our notorious classmate, Dave Moskal, in a mock closing argument. The landmark case on which the exercise was based involved a personal injury arising out of the allegedly negligent maintenance of a power line. I remember well Ray’s “jokester antic” and my resultant 15-minutes of fame.

Late in class on a Friday in early October, Professor Steenson’s lecture touched on the aforementioned case. He then asked for volunteers to present the following Monday, a re-enactment of closing arguments. The instant Steenson said, “Anyone for the plaintiff?” Moskal’s hand shot straight up. No one was surprised. In fact, a couple of students groaned. Moskal was the champion brown-noser of our class. There was never a session in which he didn’t ask multiple questions to show-off his superior knowledge; never a class after which he failed to make a bee-line for the professor to engage in more show-off talk as if Moskal were a peer of the prof, not a first-year student. If you got him talking—which I made the mistake of doing once during a break—you learned that he had his sights on politics, first the state legislature, then Congress, then . . . the White House itself. (Tragically, he blew himself up before he could fulfill such ambitions. In the years following law school he became a highly successful personal injury plaintiff’s lawyer and made tons of money. He then went rogue and was caught stealing funds from a client’s trust account. For that he went to prison and met an early and ignoble death.)

Professor Steenson proceeded to ask for a volunteer to assume the role of defense attorney for the power company in the case. No one volunteered—until Ray, sitting beside me, reached furtively, grabbed my arm and raised it into the rarified air above the “L through R” row of the staggered-height classroom seating. “Eric wants to volunteer,” said Ray. In mirthful reaction—class was winding down on a Friday, after all—I half-heartedly went along with the joke. Professor Steenson, however, took it seriously. “Mr. Nilsson? Good. You’ll represent Northern States Power. Thank you, Mr. Moskal and Mr. Nilsson. We’ll reserve time Monday for arguments. Okay, class dismissed. Have a nice weekend, everyone.”

My predicament then hit me. I’d planned some long workouts for the beautiful fall-weather weekend. Now I’d have to bother myself with preparation for a volunteer assignment instigated by my rapscallion friend, Ray Peterson. When this reality set in I was not pleased. Nevertheless, I rose to the occasion—especially after Ray himself goaded me with the imperative, “You can’t let Moskal win!”

The following Monday I donned my three-piece suit and prepared for battle. Moskal went first. In the course of his monologue, he wrote some words on the large portable chalkboard facing the class. One of the words was “maintenance,” except he misspelled it, maintainance. On my legal pad I wrote, “He can’t spell!” and shifted it to Ray, who winked at me and jotted in response, “Better than mentenance.” When my turn came, I strode down to the front of the class, and before speaking, looked conspicuously at the chalkboard and feigned a double-take. With bold strokes I erased “maintainence” and wrote “maintenance.” The class burst out laughing. If my opponent had been anyone else in class, I wouldn’t have made such an obnoxiously snarky move, but Moskal had it coming, and the class knew it. Even the usually serious Professor Steenson allowed himself a publicly displayed chuckle.

I then delivered my well-rehearsed retort to Moskal’s argument. In the vote that followed, I won a decisive victory. I couldn’t be sure if it was on the strength of my performance or the universal dislike of Mr. Moskal.

(In a post-script . . . 20 years later I ran into Professor Steenson at a Taekwondo tournament in which he, as an elder stateman, and our younger son, Byron, a gunner, were competing. We chatted for a minute during a break in the action. The topic was Taekwondo, not torts.)

[2] Minn. Stat. § 65B.43, subd. 3.

1 Comment

Remind us to tell you our Moskal stories.

Comments are closed.