FEBRUARY 12, 2024 – (Cont.) More than a year and tens of thousands of miles later, I was back in Minnesota. The earth being a sphere, my “runaway route” brought me back to my point of beginning. I had flirted with far-flung risks, interests, opportunities, and possibilities that stretched my imagination and more critically, my self-knowledge. Contentment was not something on the other side of the world waiting to be discovered. It was entirely internal; an outlook, a state of mind, an attitude.

Along my circuitous route to the farthest terra firma from home (Rottnest Island in the Indian Ocean off the coast of Perth, Australia) and across the remotest regions (the Australian Outback; the entire length of Siberia—both ways) from anywhere, I pondered increasingly the possible life paths beyond the one over which I was then traveling. As part of a possible “Plan D or E,” I sent postcards to my friends and supporters back at Briggs & Morgan.

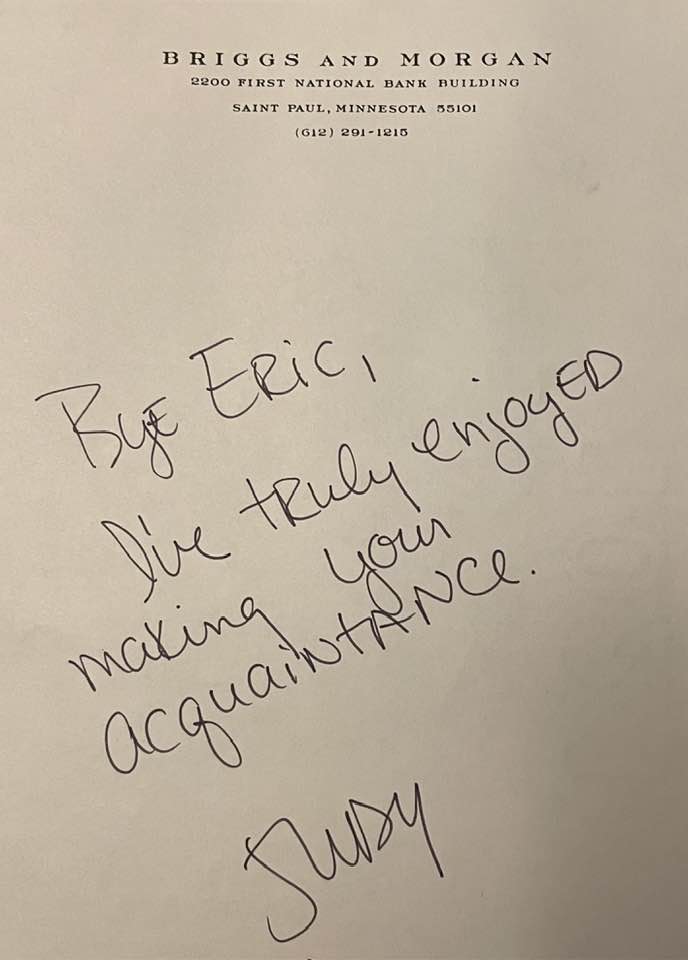

Upon my return to “reality” in early 1981, I put on my best of two suits and made a very deliberate but unannounced visit to the firm. Judy, the forever receptionist, welcomed me warmly and graciously. This was a good sign. She was a fixture long pre-dating my association with the firm; a person who’d assumed an astonishing level of universally recognized self-importance and who back in my early messenger days had treated me as the smallest claw of the bottom bird on the totem pole but who, over time, had warmed to me considerably and in the process revealed the better angel of her nature. At the end of my clerkship, she’d even penned me a kind note.

“May I roam a little and visit with people?” I said with deliberate deference.

“Of course, Eric! Go right ahead,” she said. “I’m sure people will be glad to see you.”

With that generous license, I spent the next hour strolling about, casually dropping in on people who weren’t in the midst of a crisis or deep in concentration. My first stops were in the litigation department, which was closest to Judy’s gate-keeping operation. Nearly everyone was in and readily accessible, including the department head, Dave Forsberg, one of the firm’s most highly regarded attorneys.

The most notable exception to accessibility was Jack Kenefick. No surprise there. During my year as a messenger and my eight months as a law clerk there had never been a time when he wasn’t on the phone when I happened to walk past his office or arrived at his doorway to pick up the latest research/writing assignment (he was the appointed coordinator). I used to joke to myself that the soft-spoken Mr. Kenefick was so reserved he simply pretended to be on the phone so he wouldn’t have to talk to anyone in person. On the occasion of my “return tour” he was (still) on the phone, but he acknowledged me with a wink and a wave. During my clerkship I’d had a good rapport him—when he wasn’t on the phone.

In the course of my conversations during that firm visit, the inevitable question came up (“What now for Eric?”) and my ready reply (“Well, it sure would be great to go to work with the finest people I’ve met anywhere in the world, the people right here in this office”), and the cross-my-fingers response: “Really? You want to join Briggs? That would be great!”

Wheels were set in motion, and several days later Jack Kenefick was on the phone, this time with me. “The recruiting committee is meeting late this afternoon,” he said. “It’s really a formality, and we should be able to get an offer letter out in the next day or two.”

I was ecstatic in my disbelief of my impending full redemption. In the moment I recalled silently my essay about the “double flub” and recovery of Vladimir Horowitz at Carnegie Hall.

But I had not yet broken the tape at the finish line of the race. The next morning I was awakened by my mother’s voice calling up to my bedroom at the top of the staircase. “E-e-ric! Telephone. It’s Briggs & Morgan.”

I bolted from under the covers, caught sight of the bedside clock—just past 8:30—and dashed down the hallway to the upstairs extension phone.

“Hello?” I said with a voice barely 10 seconds new to the day.

“Hi, Eric. Jack Kenefick here. Good morning.”

“Good morning.”

“We’re all set to go, but at yesterday’s meeting we realized we didn’t have your law school transcript. Not a big deal, just a formality. We don’t need it, but just for the record we should know what your class rank was. Do you know?”

The blood rushed from my brain. At the very finish line victory was to be denied. As I imagined myself going airborne off the track, involuntary synapses assembled a response.

“Gosh, Jack,” I said. “It’s been a while—going on two years now. I can’t tell you exactly [the truth], but I know that I was in the top 97 . . .”

I remember the very next instant and the bizarre sensation of my tongue disconnecting from my brain. Untethered, the tongue said, “percent” with a full stop after the second syllable—also the truth from a hyper-technical standpoint.

“That’s what we all thought,” said Jack. “We’ll get the letter out today.” He then told me what my starting salary would be, and after recovering from the shock I’d just sustained, I felt faint all over again. Having avoided a cataclysmic end, I broke the tape and won Olympic gold.

Giddy and ever so grateful, I proceeded to do the ridiculously outrageous: after receiving the offer letter, I phoned Jack to ask if I could push the start date out from April 1 to August 1. I’d been training for the Stockholm Marathon scheduled for early June. In addition I’d planned to drop down to Poland, where the Solidarność revolution had been crushed the previous December. Having explored the country in depth back in August and September, I wanted desperately to return to observe the changes (and take precious food to friends)—one last fling before I really settled down “once and for all.”

The firm was more than accommodating, and in fact, soon after I did start, I was given the lectern at one of the firm-wide weekly breakfast meetings at the Minnesota Club to tell about my wanderings. It was an attentive crowd, and no one left early. People were eager to ask me questions afterward.[1] This was important to me. I wanted to be known for more than my running, pantomimes, imitations, and research memoranda. I wanted to be taken seriously, despite my constant sinking feeling that I was not qualified to be a lawyer, least of all at the venerable firm that had so graciously welcomed me into its fold. (Cont.)

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2024 by Eric Nilsson

[1] This “side gig” acquired a life of its own. A few weeks later one of the shareholders, a former FBI agent, asked me to give the same presentation at a monthly lunch meeting of retired agents. They were a serious bunch. Later, after a chance encounter at the athletic club with the amiable Justice Donald Lay, Chief Judge of the U.S. Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals, he invited me to a lunchtime court staff meeting to give a talk about my travels. The judge was himself quite curious and asked many questions. Somewhere I have his kind letter of appreciation. Soon thereafter I began to receive other invitations to address various groups, each of which had some “legal” connection.