FEBRUARY 11, 2024 – (Cont.) While most classmates I knew had signed up for the formal daily in-class review sessions for the bar exam, I bought only the materials and decamped for the cabin. The last place I wanted to spend June and July was inside a stuffy auditorium at the prison from which I’d just been released. I’d study entirely on my own—on my own time and terms.

Except for weekends, when my parents would drive up to join me, I had the place to myself. I went for long runs, rowed the old Alumacraft along our shore every day, sailed in the afternoon if the breeze was up, and wrote long letters. For a solid six hours a day I studied—hard. Linked to my horrible experience throughout law school, that summer felt like the end of a marathon in which I’d been crippled by blisters, dehydration, strained muscles, and the build-up of lactic acid. Those setbacks had ruined any chance for a PR (personal record) and had nearly forced me to abandon the race altogether. Somehow, though, I was still putting one foot ahead of the other.

As our legal ethics prof had said on the first day of class our second year, “Welcome to your second year. You’ll all now finish law school whether you like it or not.” Likewise, I’d now finish the marathon “whether I liked it or not.” I would dig down—way down—study my butt off and pass the damned bar exam. Then and only then would I be truly free of the trauma of law school and the mistaken notion that I’d “wanted to be a lawyer.”

I returned from the Northwoods to my parents’ home (just before graduation I’d moved out of my apartment) two days before the bar exam. In the late afternoon of the next day, Ray Peterson and Bruce Goldstein from my study group were planning a final study session with a third member, Dan Toohey, at the latter’s home near Lake Nokomis in Minneapolis. They invited me to join them. More to calm our nerves than to tighten our grasp of the law, we went over a few basic principles in each area that would appear on the exam. Eventually, however, our collective nervousness yielded to Ray’s wit and Bruce’s one-liners. According to part of the pre-announced plan, someone suggested it was time for a group run around the lake.

The idea was to go for a light jog to relax our minds and nerves. Bruce and Dan were in decent shape but not competitive runners. All of us—Ray and I included—wanted to conserve our energy for the morrow; none of us assumed a blistering pace.

Afterward, Dan grilled some burgers, accompanied by pop, chips, and condiments. We then agreed it was time to disperse for a good night’s rest ahead of the exam. Ray had invited me to stay at his house overnight instead of traipsing all the way back to my parents’ house in Anoka, then driving the next morning 40 minutes back down to the Civic Center on the edge of downtown St. Paul where the test was to be administered. Ray’s house was a three-minute drive from the Civic Center.

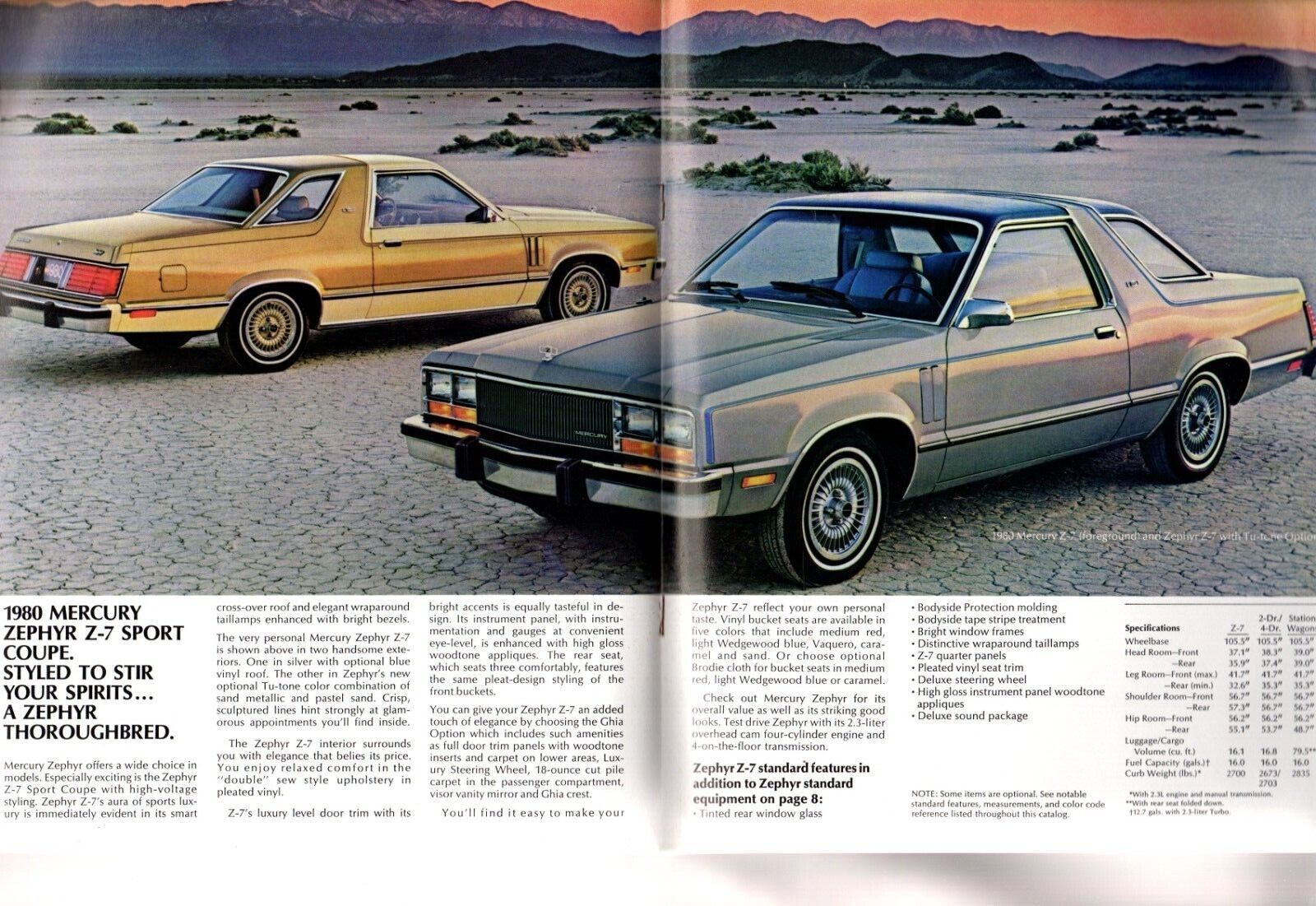

At around 7:00 on that fateful evening before the exam, Ray and I said good luck and farewell to our two compatriots and set out for the 20-minute drive to his house. Ray had just bought a brand new two-toned Ford Zephyr coupe. Throughout our time in law school Ray had given me numerous rides from school to my apartment a half mile away before reversing direction to his house less than a mile on the other side of school. I’d always observed him to be an attentive driver.

After backing out of Dan Toohey’s driveway, Ray shifted into drive. Within two blocks we achieved cruising speed. We didn’t need to slow for the first intersection, since stop signs controlled the perpendicular approaches to our route; same at the next intersection, except . . .

. . . A big sedan was approaching at a right angle on my side so fast that neither of us saw it coming. It entered my peripheral vision just as we reached the center of the intersection. Blowing the stop sign, the speeding vehicle was suddenly upon us.

“Look out!” I screamed. With a deafening crash the errant car smashed into ours right behind the back of my seat. We spun around violently as if we were aboard a wild midway ride gone insanely rogue. Ray’s glasses flew off his face, struck my left temple and rattled around the inside of the car. By the time everything came to a stop, we were facing the same direction as at the instant we’d been struck. The Zephyr had been walloped around a full 360 degrees.

I smelled gasoline and knew instinctively we had to get out of the wreck before we were consumed by a fireball.

“You okay?” asked Ray in panic.

“We’ve gotta get outta here now,” I said, not sure of my condition but not wanting to die of incineration. Once I’d freed myself of the seatbelt and climbed out, I realized I had a pounding headache. I saw Ray exit his side of the car and stumbled behind him toward the grass on a corner of the intersection. The lot was occupied by a church, and upon reaching the lawn, I collapsed on the ground—more from shock than injury. I closed my eyes expecting the car to blow up any second. When it didn’t, I raised my eyelids and looking straight up saw the church steeple against the clear blue sky. Someone’s watching out for me, I thought. Wait . . . Maybe it’s God himself.

Soon we heard the approach of sirens. A few minutes later I was in the back of an ambulance racing to Hennepin County Medical Center in downtown Minneapolis. Uninjured but seriously shaken, Ray rode shotgun.

An ER team rushed to receive me as the EMS crew wheeled in the gurney. After my vitals were checked, my head was examined—in a most literal sense—but not in a manner that would surely occur in the modern age; no MRI, no definitive testing for TBI, just questions—Was my vision blurred? (No) Did I have a headache? (Yes) Did I feel nauseous? (No).

Ultimately the doc in charge said I should stay overnight “for observation.” I was alert enough to recognize his statement as a major fork in my life’s journey: I could heed his advice, but if I did I’d surely miss the early start of the bar exam and be excluded from taking it this time around. Chances are I’d never again study for it or sit for the exam the next time it was offered, six months later—or ever. The medical advice was an ironic opening; a golden excuse for me to bail out of my troubled relationship with the study of law. In the moment, however, I managed for once to make what time would affirm as the better choice: go to bed with a headache and take the exam the next morning.

The nurse gave me some aspirin, and Ray and I waited for his wife Terri to pick us up.

While I lay sprawled on Ray and Terri’s living room sofa, Ray was on the phone—first with Bruce Goldstein to tell him what had happened, then with the mother of the kid who’d rammed us. Ray seethed when he learned the kid had lied to the mom and the police, claiming we had blown the stop sign. Ray’s anger increased when he was unable to get through to his insurance company on their 24-hour claims number. It was after midnight before we even tried to go to sleep.[1]

Early the next morning, Terri dropped us off at the Civic Center. Bruce and Dan, with whom we’d plotted our final preparations so carefully, had arrived ahead of us and informed common acquaintances of the car accident. Word spread like wildfire. In a crowded corridor where I sought access to a drinking fountain before exam time, I heard a total stranger tell two others I’d never seen before, “Did you hear about the two guys who got in a terrible car wreck last night? Apparently, they’re here and taking the exam! They must really be gunners.”

At the appointed time we hordes of recent law school graduates were allowed into the main hall of the center where folding tables and chairs filled the space. Six or eight chairs surrounded each table. We found our assigned seats and waited for the tests to be distributed. When the main proctor gave the signal, everyone—a “gunner” or otherwise—went to work on the final make-or-break major hurdle to becoming a lawyer.

My headache had diminished, thanks in part to Terri—who, after all, was a pharmacy graduate student—having supplemented my Wheaties breakfast with extra-strength Tylenol. I opened the test and began reading the first question of the first section—civil procedure. The question involved personal and subject matter jurisdiction: “A, a resident of Iowa, is injured in a car accident in Minnesota involving B, a resident of Wisconsin . . .”

A car accident! I nearly laughed aloud.

For the two-day exam, I maintained my concentration. By the end I was confident I’d passed (it was graded on a simple pass-fail basis), but it would take several weeks before the results were mailed out. I was in New Jersey, ensconced in my grandfather’s business, such as it was, when the letter arrived at my parents’ home back in Minnesota. Mother called that evening and asked what I wanted her to do with the envelope—open it or forward it. By this time, I’d moved on psychologically. The result was more a matter of curiosity than it was a checkpoint to my future. I told her to go ahead and rip it open.

“It says here . . .” she said, “. . . uh, let me see . . . oh yeah, here. It says you passed.”

In January I quit New Jersey to return home to Minnesota and make final preparations for my Grand Odyssey around the world. (See blog posts 1/22 – 4/22.) One goal I had for the journey was to scour the globe for my vocational destiny. My undeclared motivation, however, was to run away from myself and start life over. In any case, at that juncture I was certain the prospects of a career in law were all but dead and buried.

Nevertheless, having endured so much and still smarting from that F in insurance law, I decided to take one last step before throwing dirt on the coffin of my brief and painful law career. I would submit my formal application for admission to the Minnesota State Bar and get sworn in. This involved a trip to the state capitol building, and out of convenience and to coordinate other errands I needed to run, I spent the night at my sister and brother-in-law’s apartment on Ramsey Hill, a mile or so from the capitol. The swearing in ceremony was scheduled for 9:00 the next morning in the Supreme Court chambers.

Not having a car at that point and my hosts having to use theirs at that hour, I decided to walk. The outside temperature was aggressively cold—well into subzero Fahrenheit territory—and besides, being accustomed to running tangents on every marathon training course, I chose the most direct route, not necessarily the easiest one. Soon I was climbing over chain link fences and other barriers, including a row of shrubs that snagged my overcoat. By the time I reached the capitol steps I looked like a gulag escapee, overcoat torn, eyelids frozen half shut and stalactites hanging from my nostrils. When I caught my frightening reflection in the window of the big front door of the elegant capitol, I looked more like a guy who’d flunked insurance law than a soon-to-be sworn-in lawyer destined for the actual practice of law. (Cont.)

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2024 by Eric Nilsson

[1] In a most amazing sequel to the story, Ray had his totaled brand new car towed to a collision repair garage that sawed the vehicle in half to salvage the front half, which was unscathed. The repair experts then located an identical brand new Zehpyr whose back half had survived a bad crash. The two halves were then spliced together, and by way of such collision repair artistry, Ray got his car restored. But three months later he called to inform me of the post-script to the sequel: a few doors before while driving home on I94 from Madison, WI, he and Terri had struck the broad side of a large deer. The collision had completely destroyed the front half of his car—the half that had been recovered from the crash on the eve of the bar exam. “This time I’m not going to bother with a transplant,” he said. “That car—both halves—was jinxed.”