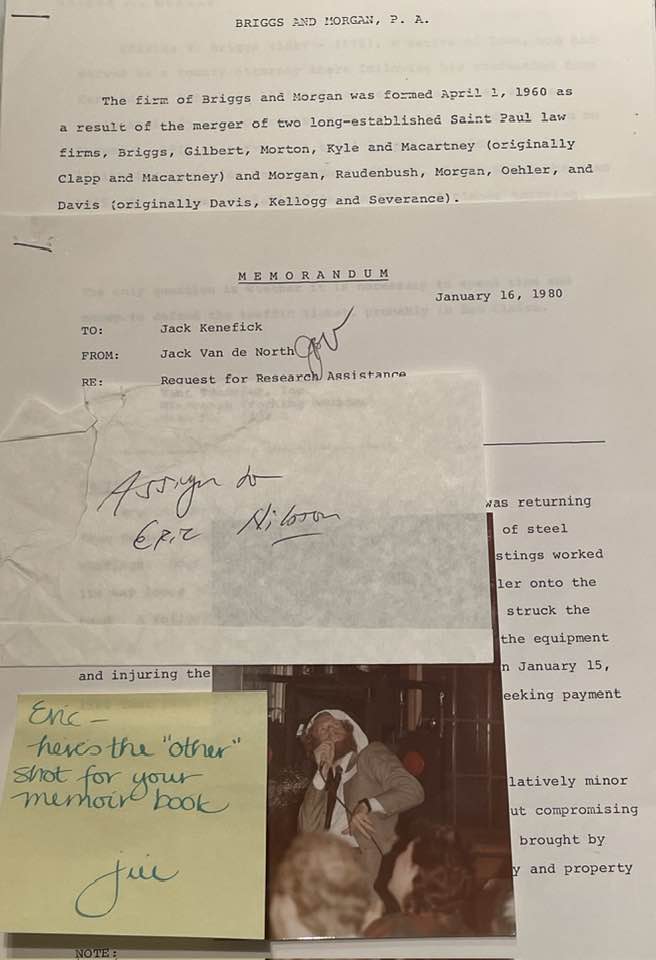

FEBRUARY 10, 2024 – Coincidentally, just before graduation, Briggs & Morgan held its annual firm-wide dinner party at the venerable Minnesota Club a few blocks away. I thoroughly enjoyed the occasion, as I hobnobbed with a wide circle of friends and acquaintances. On demand emanating from a table well-supplied with beer and wine, I took to the floor in front of the lectern and speakers walked back and forth, imitating various members of the firm. I then branched out with my repertoire of pantomimes. With the aid of the crowd’s consumption of alcohol, my ridiculous (in retrospect) show brought abundant applause.

Later, after things had simmered down—or rather the opposite, when the dance music was cranked up—a partner on the recruiting committee, Jack Van de North, a genuinely nice guy for whom I’d done some assignments and who was universally respected, approached me and suggested we repair to an adjacent hallway where we could hear ourselves think. We talked a while, and at a momentary break, Jack asked what my post-graduation plans were.

“Aside from taking the bar, I really don’t have any,” I said. “I’m not sure I want to go into law.”

“Really?” said Jack. “You should.”

In my head, his initial question and reaction to my response opened a wound. If he only knew, I thought. But then came an outright shock.

“You should think about joining Briggs & Morgan,” he said. “We’d really like to have you.”

I was dumbfounded at the same time I was shattered. If only . . . I thought. If only at the outset of law school I’d known this conversation was going to occur, I would’ve applied myself. I would’ve continued my dedication throughout college and achieved corresponding results. You short-sighted idiot! I shouted at myself bitterly.

It was my turn to say, “Really?” I then added, “I’m flattered. Really, I am, but . . .”

“But what?” Jack asked.

“I’m just not sure I want to practice law.” Yet, at the same time, I wanted to pretend that the flattery had more substance to it than my law school GPA could ever sanction. I didn’t want to kick the silver platter out of the partner’s hands, even though I knew it would prove to be illusory if put to the test. “Maybe someday . . . after I’ve pursued some other goals I have.”

Upon leaving the party I had the urge to call Ray Peterson, whose well-meaning humor over my abysmal academic performance had actually helped sustain me to the bitter end of law school. He’d be flabbergasted by my dumb luck. He would’ve drooled all over the chance to join Briggs & Morgan.[1] His reaction when I called the next day was exactly as I’d predicted.

A few days later my clerkship reached its pre-set term. I was given a hearty send-off by the firm, complete with cake and ice-cream. It was a joyous occasion tinged with sadness and shadowed by something darker. I had developed many wonderful friendships and basked in the kind and generous words—spoken and inside cards—of the many lawyers and staff members who attended the farewell gathering. On the flip side, I was sad to be moving on.

But amidst the good cheer of the event, that familiar demon—my lousy law school academic record, dragging the F in insurance law like a ball and chain—darkened my thoughts. As much as I liked the firm and the firm liked me, I knew that notwithstanding the extraordinary conversation I’d experienced with Jack Van de North, I could never be hired as a full-fledged lawyer. Despite appearances, I was a giant loser, and none of my well-wishers had a clue. After the celebration ended, I left with a heavy heart. I caught a bus to my apartment on Grand Avenue, 15 minutes up from downtown. On the ride I composed a letter of appreciation to the firm and typed it out as soon as I got home.[2]

* * *

I treated graduation as if I’d been released from prison after serving time for the gross misdemeanor of academic malfeasance. My mother was out of town—helping UB plug holes in the dike of my elderly grandfather’s business concerns. Dad, who’d always wanted to be a lawyer and could’ve been an excellent one, attended proudly, living vicariously by way of my ostensible achievement of graduation (I’d managed to hide from him my god-awful record and class standing.)

Commencement exercises were held inside the crowded cavernous sanctuary of the historic House of Hope Presbyterian Church across the street from the law school. In a moment of pre-meditated immaturity, as soon as the dean handed me my diploma, I pulled a bright red Mickey Mouse cap out from under my robe and switched it out for my mortarboard and tassel. I’d pulled this stunt on a dare from Ray Peterson and Bruce Goldstein, our mutual friend, jokester and member of our study group. A ripple of chuckles, contained mostly to a few rows in front, accompanied Ray’s out-loud “Ha!” and Bruce’s “Go Eric!” in the otherwise stately proceedings. Dad was mortified. The instant he caught up with me after the ceremony, I realized I’d committed a crime far worse than having flunked insurance law. Dad refused to speak to me.[3] (Cont.)

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2024 by Eric Nilsson

[1] That being said, Ray did just fine for himself, building a lucrative practice specializing in workers comp claims. Prior to that, he’d landed a plum job in the U.S. District Attorney’s office. As part of his application he’d put me down as a reference and told me, “You might get a call from the FBI conducting a background check.” Time passed but no call. One Saturday morning weeks later I heard a knock on my basement studio apartment door. I’d been up late the night before carousing with friends and as a result was sleeping in—on my Murphy bed, which extended to the door. The knocking startled me. “Just a minute!” I said. I leapt out of bed, jumped into a pair of jeans, and so that I’d be able to open the door, I folded up the bed—unmade—back into the recess in the wall. I then peered through the peephole of the apartment door—a small opening without glass but with a metal frame and little crossbars that reminded me of something out of a Medieval dungeon. Outside the door stood two gentlemen in dark suits. Who the hell . . .? I thought. But in that instant I thought of Ray’s having put me down as a reference. Maybe they were a couple of FBI agents wanting to meet the “reference” in person. Without giving it further thought—nor considering the possibility that I looked like a fugitive or otherwise a big-time loser—I opened the door and said, “You must be from the FBI.” The first thing I noticed about them was the shock on their faces. They turned out to be Jehovah Witnesses. I’m sure they thought I was a fugitive or a big-time loser, and in any event, a soul to be saved. They accepted my invitation to step into my humble apartment while I scrounged up a crate and folding chair from which they could proselytize from a seated position. I told them up front that I wasn’t “buying,” but that I was nonetheless curious about their backgrounds and what motivated them to take a chance on people like me. The free-ranging conversation was worth the price of admission.

[3] Nearly 25 years later I seized a chance for redemption. My wife and I and our two teenage sons were visiting my parents one Saturday. Over lunch we got to sharing anecdotes about various snafus and mishaps in our lives. With dessert came the inspiration to tell the story of my Mickey Mouse hat at graduation from law school. At the outset of the tale I decided to turn it into an object lesson for our sons. “Guys,” I said, “I’m going to tell a story that I want you to listen to very carefully. It’s something I’m not at all proud of; something for which I owe your grandpa a huge apology; something that’s gone unmentioned all these years and now needs to be said.” I then told the humiliating “Mickey Mouse” story and apologized profusely to Dad. In a happy mood to begin with, thanks to the generous serving of frozen yoghurt and chocolate syrup before him, he threw back his head with a big laugh. “You didn’t have to apologize,” he said, wrecking the point I was trying to establish for the young ears at the table. “You’ve more than redeemed yourself.” Cory and Byron joined their grandfather’s mirthful reaction. To salvage what I could of the intended lesson, I maintained a straight face and said, “No, Dad—and Cory and Byron—I really mean it. I’m sorry. deeply sorry for the disrespect I showed.” He reached out and patted the back of my hand.