FEBRUARY 23, 2024 – (Cont.) No one was the wiser to Ray’s little escapade with the 55-gallon drums. The guys in the haz-mat suits did their thing, oblivious to the fact that Ray and his buddies dressed in ordinary work clothes had loaded up the drums, ferried them all the way across town, unloaded them in Ray’s driveway, then re-loaded them and carted them back to the farm. Certainly no one at the bank besides Ray and me had a clue. For just over $20,000, I learned that the drums contained residual amounts of fuel oil and concrete sealer that I’m sure would’ve killed anyone who mistaking them for Mountain Dew. But no one drank the two or three gallons of leftover toxins, and the contaminants and drums that contained them found proper, legal disposal—the cost of such was included in the $20,000.

With that episode behind me, I was now in a position to get the property under contract. The shell buyer was represented by a reputable law firm, and after the usual back and forth between lawyers and between the buyer’s front man and me, the purchase agreement was finalized and executed.

If the deal closed, the purchase price would make me the hero for a day, or at least for the duration of the 60- to 90-minute meeting of the oversight committee when I’d get to report that the deal was done and proceeds booked.

The committee included the bank president, the chief credit officer, the head honcho of all real estate lending, the head of our department, and us four “Special Assets” portfolio managers, including Ray and me. We met every two weeks to go over our pending workout files, many of which were endlessly convoluted, especially the three or four files that had been assigned to the senior manager, Bill McRostie.

If Ray had been at the bank for a million years, Bill was a relative newcomer—to the bank, but not to a wide range of experience. He was an old buddy of Jerry, the brilliant chain-smoking, hard-drinking head of our group. I’d always thought there were plenty of very bright people at Briggs & Morgan, but I soon found that Bill and Jerry were the intellectual equals of any of the leading “scholars” at the law firm.

I would never learn much about Jerry’s background—he never talked about himself—but he was a major talent. In analyzing the most complicated situations and plotting exit strategies, he was an almost frighteningly quick, incisive, and thorough thinker, and he was invariably correct in his predictions. He was always accessible to talk things through, and at the bi-weekly oversight committee meetings, the higher-ups listened carefully to what Jerry had to say and without exception followed his recommendations. Early on I could see the value of his endorsements, and I made sure they were secure before I presented my own status reports to the committee.

Bill McRostie was another unusual character. Little by little I learned the impressive details of his curriculum vitae before signing on at the bank. In WW II he’d been a fighter pilot in the Pacific. He then pursued a career as a freelance trombone player at some of the more renowned jazz clubs in New York City. Somewhere along the line he went to law school, practiced a while and eventually worked a stint as the New York-based states-side general counsel of Olivetti, the Italian typewriter manufacturer. Later he returned to his native Minnesota to become a real estate developer, of all things, before his first retirement. He re-emerged as in-house counsel for the Chanhassen Dinner Theater until Jerry “drafted” him to come work in “Special Assets.”

In addition to being a truly nice guy and a couple of years older than my dad, Bill was remarkably well-read, and an experienced carpenter and home remodeler. He was conversant in just about any topic you brought up.

I’ll never forget my first day on the job—specifically lunch with Bill and Jerry. I’d brought my running gear to the office and had planned to continue my usual noontime routine while at Briggs & Morgan: change at the Athletic Club, now just one block farther down the street than I’d been at the firm and go for a 45-minute, all-out run. When Bill and Jerry stopped by my office to see if I wanted to join them for lunch, I listened to my better judgment and accepted the invitation of these two law and banking veterans.

It was not a lunch that would happen in today’s world. We went to a nice, quiet sit-down place a block away. Bill competed with Jerry for number of cigs-per-hour, and each of the gentlemen ordered martinis. I stuck with water, and being a runner, politely declined Bill’s offer of a cigarette.

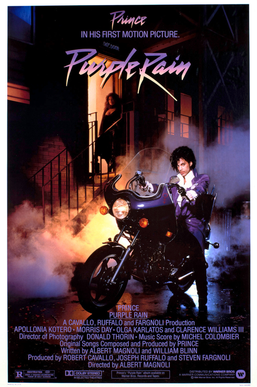

The conversation that ensued was mind-blowing. After talking for a bit about biz, Jerry asked Bill what he’d done for excitement over the weekend just past. The craggy-faced Bill, dressed in his signature gray, three-piece suit, let out a puff of smoke and said, “Doris and I saw Purple Rain.”

“Oh yeah?” said Jerry, as the smoke he exhaled mingled with Bill’s. “What did you think of it?”

“Absolutely loved it,” said Bill. “Prince is a genius. There’s no doubt about that.” I tried to imagine that assembly of words coming out of my dad’s mouth. I couldn’t. I doubted that my dad had even heard of Prince.

After Bill’s impressive discourse on Prince’s music, style, and lyrics, the conversation shifted to the presidential campaign—Reagan vs. Mondale. I’d assumed that these two guys were dyed-in-the-wool Republicans, though after Bill’s review of Purple Rain, I was now left to wonder. My altered assessment was validated as Bill launched into an articulate and well-informed critique of Reagan and Mondale, coming down decidedly on the side of the Democrat Mondale. Jerry nodded in agreement.

As the senior statesman, Bill walked on water at the oversight meetings. By his elucidations, I felt I was learning at the feet of the undisputed master of real estate workouts. In the course of my career since, I’ve encountered few lawyers or turn-around experts as brilliant as Bill. And as I said at the outset, he was a truly nice guy, low-keyed without any need to impress others, and during the year I spent in “Special Assets” before returning to Briggs, we became good friends.

After I resumed my law practice back at the firm, Bill sent me several files, including a particularly complicated one with a relatively high profile, and learned even more in the course of working through gnarly issues. One of the pinnacle moments of my entire career was during a phone call after he’d reviewed my draft brief in support of a motion for summary judgment in the particularly nasty case he was managing from the inside and I was handling as outside counsel. “Excellent job on the brief,” he said in his gravely voice. When Bill handed out a compliment, he meant it, and no compliment would have greater currency than his.

But I digress in time and space.

Because the “55-gallon-drum-farmland” in my portfolio back at the bank was carried on the books at a vastly reduced value (the appraised value hadn’t caught up to a precipitous increase in that particular market area), the purchase price that my buyer was willing to pay would produce a hefty profit. Once I could happily report closing on the sale, the oversight committee would have something to cheer about—namely, over a million bucks dropping straight to the bottom line. Depending on what else was on the agenda for that meeting, the senior execs might even clap, and until adjournment, at least, they’d be pleased with the performance of the youngest kid on the block.

What none of us knew at the time I informed the committee that the property was now under contract, is that I was about to get the bank and myself mixed up with . . . the ancient science of soul travel.

On the surface everything looked felicitous and above-board: the front man from California, the buyer’s local lawyers, the terms and conditions of the purchase agreement were all patently normal and businesslike. The deal was for cash, so no worries about passing umpteen hurdles on the part of a lender financing the buyer’s acquisition. The condition of title presented no challenges, and the environmental contingency was straight forward—now that we’d disposed of the 55-gallon drums (twice if you count Ray’s clandestine operation). The only other significant condition was city approval of the buyer’s application for a conditional use permit for development of the property, but for that challenge the buyer had astutely hired one of the most prominent local land use law firms in the Twin Cities.

The plan, we were informed, was to construct a “headquarters campus” for the entity behind the buyer. We were provided a set of preliminary drawings for the low level buildings to be constructed on the sprawling farmland recently annexed by the city of Chanhassen, which coincidentally is where Bill McRostie lived. Surely no one would object. They would be architecturally attractive and well-suited for the surrounding land. There were no immediate neighbors to worry about, and for the most part, much of the contemplated complex would be hidden from view of the highway that ran from Chanhassen westward toward the rural sunsets.

I figured the skids were greased for approval of the site plan. The city’s planning commission had given the project a preliminary “thumbs up,” and I anticipated formal approval by the full council. Lawyers Bob Hoffman and Peter Beck of the Larkin, Hoffman, Daly & Lindgren firm were top drawer, and in the run-up to expected approval, I’d established a close rapport with them and was confident they could carry the day.

But then all hell broke loose. (Cont.)

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2024 by Eric Nilsson