FEBRUARY 5, 2024 – (Cont.) Two o’clock came and went without any word from the other lawyer. I didn’t need the stress. Since my phone call with him mid-morning, I’d been besieged with calls and emails on unrelated matters—matters of consequence for regular clients. The last thing I needed right then was the worry that I’d actually have to prepare for a trial the next day; mostly to avoid complete professional and reputational embarrassment. Why, oh why had I signed up for this pressure?

At around 2:30, Sue dropped by my office to ask if I’d heard a response yet.

“Nope,” I said. “I think they’re playing a game of unilateral chicken; making us think they’re going to trial; making us actually prepare for it but planning to meet us just outside the courtroom tomorrow with a counter offer. They know the thirty-five hundred will still be good, despite our deadline of 2:00 today. They’ll offer to settle for six, we’ll hold firm at $3,500, and after going through the motions, they’ll drop to five and eventually accept the thirty-five hundred.”

“Don’t you want to call or email him this afternoon to see if he’s talked to his client about our offer?” asked Sue.

“Oh, I’d love to, but can’t; just can’t—unless you’re willing to settle for more than thirty-five hundred bucks,” I said—reluctantly. I wanted in the worst way to be done with the matter, but I resisted. By imposing the 2:00 deadline for a response to our settlement offer, I’d essentially precluded follow-up initiative on our part without ceding advantage. And from the other lawyer’s perspective, even if he’d been unable to reach his client by 2:00, he’d be signaling weakness by asking for more time—especially if he assumed that no such deadline was truly a drop-dead deadline.

When 4:00 rolled around with no call or email from the lawyer, my “game of chicken” assessment gained further traction. I called John to make sure he and his two buddies could meet me at my office at 7:30 the next morning . . . to prepare their testimony for trial. I also gave instructions for how to dress. After clearing my desk—and the desktop of my computer—of other matters, at 5:00 I pulled out the Rules of Evidence, which I hadn’t reviewed since my previous trial nearly a year before.

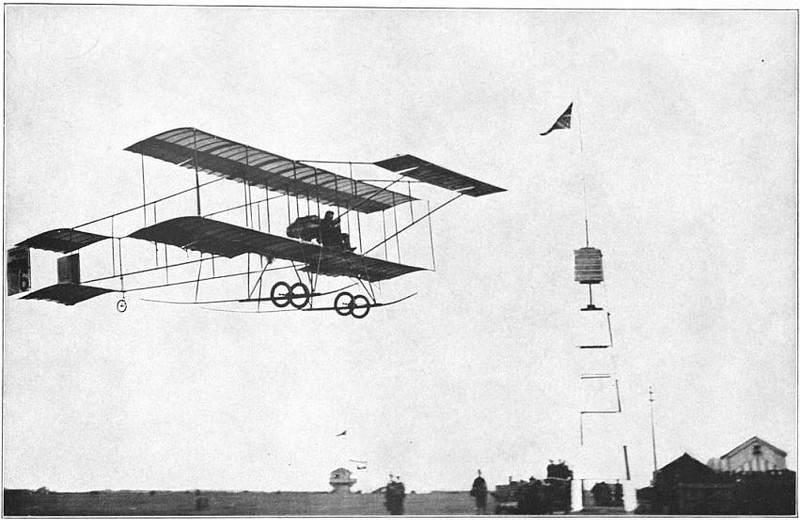

That evening, I scratched out an outline—opening statement, order of witnesses (four), exhibits (three), direct questions, potential cross-examination questions, closing argument. There would be no voir dire—the “show,” as it were, would be a bench trial. No big complicated one, either. It would be a classic “He said, she said,” case. I’d be flying by the seat of my pants. That was the bad news. The good news was it wouldn’t be a long flight. My main objective would be to avoid being the equivalent of the slow-flying plane pulling an advertising banner over the Minnesota State Fair every year—except in my case, instead of “BUY RED BARON PIZZA,” a banner with the words, “WATCH ME CRASH!”

The better news, I told myself, was that the damn case would settle outside the courtroom before my figurative bi-plane would even have to take off.

John, Skip and Jeff were in my office suite already when I arrived just past 7:30 the next morning. They looked like three honest working guys; schoolboys in their early 50s, ready for show and tell. Their handshakes and the earnestness in their eyes gave me confidence. For the next hour I compressed a day’s worth of preparation—personal backgrounds and their story down to every detail I could extract from them; a description of how the trial would likely come down; how to handle themselves on the witness stand. The preparation-on-the-fly continued on our walk to the courthouse. Apart from the facts of the case, what struck me most was Jeff’s background as a long-time auto mechanic: he certainly knew his vehicles by make and model.

“Even in the dimly lit parking lot that night,” he said, as we waited for the pedestrian light to turn, “that the sedan John bumped was not a Pontiac.”

“Shit!” I said. “What’s the car in the photographs?” On the other side of the street, I pulled one of the pictures from my skinny folder. The four of us huddled as I held it out.

“That’s a friggin’ Buick,” said Jeff.

“So she is lying through her teeth,” I said.

“And so is the bouncer,” said Skip. “They’re in cahoots!”

Minutes later we were in the hub-bub of the hallway outside the courtroom. As I pondered the revelations just outside the courthouse, John pointed out the woman—and her lawyer.

“Stay here,” I told my people. I made my way toward our adversaries and introduced myself.

“Never heard back from you,” I said, trying hard to sound nonchalant.

“That’s because we’re not interested in anything less than $7,000,” he said.

I wanted to loosen my collar. They really were playing hardball. I couldn’t believe it. Why would a $500/hr. hot-shot litigator at one of the city’s top law firms go to trial over $7,000? Sure, from an ethical standpoint the fact that for him the case was pro bono shouldn’t matter, but I knew he lived in the real world too. I knew the performance and financial pressures under which every lawyer—especially big firm lawyer—works. Above all was the risk faced by his client—the risk of the dice turning up “zero.”

“Do you want me to communicate a settlement number to my client?” I asked.

“Seven thousand,” said the lawyer, his deadpan look signaling no hint of compromise—and for that matter, no hint of personality. He was cold and inscrutable. A poker player.

“Okay,” I said. “I guess we’ll duke it out in front of the judge.”

“Guess so,” he said.

I squeezed through the crowd back to the Three Musketeers. “We’re goin’ to trial,” I said, trying to mask my consternation.

At 9:00 sharp, the “cattle call” got under way—the procedure by which multiple cases on the docket are sorted out between “settled” and “going to trial,” and of the latter, their sequence. About a half hour later, the courtroom was mostly cleared, and the judge was asking for appearances in our case. Poker Face, Esq., introduced himself and his equally humorless client. Trying my best to look human, I gave my name and John’s.

The show got underway. Mr. Big Time Litigator was underwhelming. I hoped to hell I wouldn’t be under-underwhelming. (Cont.)

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2024 by Eric Nilsson