FEBRUARY 18, 2024 – (Cont.) Each trustee bank “lawyered up.” One Texas bank, in an abundance of caution, brought two six-shooters instead of one to the fight: a primary law firm and a secondary firm to keep an eye on the primary one. Norwest retained Tom Kimer, head of the litigation department of Faegre & Benson, now Faegre Drinker Biddle & Reath. In the ultimate lawyer’s field day—make that years of field days—the group of lawyered-up trustees then hired Phillip Warden of the silk-stocking San Francisco firm of Pillsbury Madison & Sutro to represent the entire group against Executive Life Insurance Company—or more precisely, against John Garamendi, the Insurance Commissioner of California (now Democratic Congressman), given that the company had been placed in state receivership.[1]

The only sources of repayment of all those bonds were the GICs issued by a now insolvent insurance company. In a liquidating bankruptcy, the assets of the debtor are sold and the proceeds distributed among all the creditors—according to their respective legal priority. Not all creditors are treated the same. In the case of the ELIC receivership (the equivalent of bankruptcy), holders of GICs (i.e. we trustees for the benefit of our bondholders) were assigned higher priority than other creditors. If you were lucky enough to hold a GIC, you’d get a much bigger recovery than if you held some lower-form, higher-risk kind of insurance product. A central issue in the receivership thus became, “What is a GIC, exactly, and are our contracts (and payment sources for the bonds) truly GICs?”

Garamendi fought us tooth and nail, up and down on appeal. It was in the midst of this fight that I entered the scene.

For months that accumulated into years, marathon conference calls occurred at least weekly and often twice or more weekly. Participants included a trust officer from each bank—I being the one for Norwest—often an in-house lawyer from each bank, always at least one outside lawyer for each bank, plus Phillip Warden, the lead lawyer representing the whole group, along with one of his partners. It reminded me of my entire second grade class crowded at the line in the sand at the outset of a playground game of pom-pom-pull-away. Except for Messrs. Warden (a true and tried Californian) and Kimer, and I (a native Minnesotan), everyone on these calls spoke with a Southern drawl. Some, like the Hunton & Williams lawyer from Richmond, Virginia representing a Tennessee bank, spoke like Jeffersonian intellectuals, but most talked in down-home, down South metaphors, such as “That dog don’t hunt” and “He’s all hat and no cattle.”

For each of the calls I’d join Tom Kimer in his office in the Norwest Tower in the heart of downtown Minneapolis. For never less than an hour and often for an all-afternoon talkfest, we’d listen to lawyerly pontifications. It was a regular round robin affair. Everyone had to hear himself (all were men) speak—a lot, repeatedly; everyone except Tom.

Tom was the perfect combination of scholar, gentleman, and genuine down-to-earth guy who was comfortable talking with anyone about anything. And he was not the least bit full of himself. Wholly the opposite. There was a reason why he was revered among his partners and clients and respected by his adversaries. Over time we got to be good friends, and shared many common interests and outlooks. For Christmas one year I gave him a scale model of a John Deere combine for his office[2], and he gave me a collection of essays by David Sedaris. I gained tremendous respect for Tom’s intellectual integrity and emotional calm. He never showed anger or impatience toward anyone, though he exhibited greatly insightful humor in his observations about people—especially pompous lawyers.

For 99% of each conference call, Tom had the speakerphone on mute. After everyone else had worn out their voices and our ears, he’d unmute the phone, and in a tone completely devoid of affect or pretense, he’d say something such as, “Hi, everyone. This is Tom Kimer. I’m wondering if anyone’s given any thought to . . .” and proceed with an economy of words to spell out a simple tactic, strategy, or alternative way of approaching a given conundrum. He was my kind of lawyer, and if I could hardly measure up to his standard, at least it was a lofty example to which I could aspire.

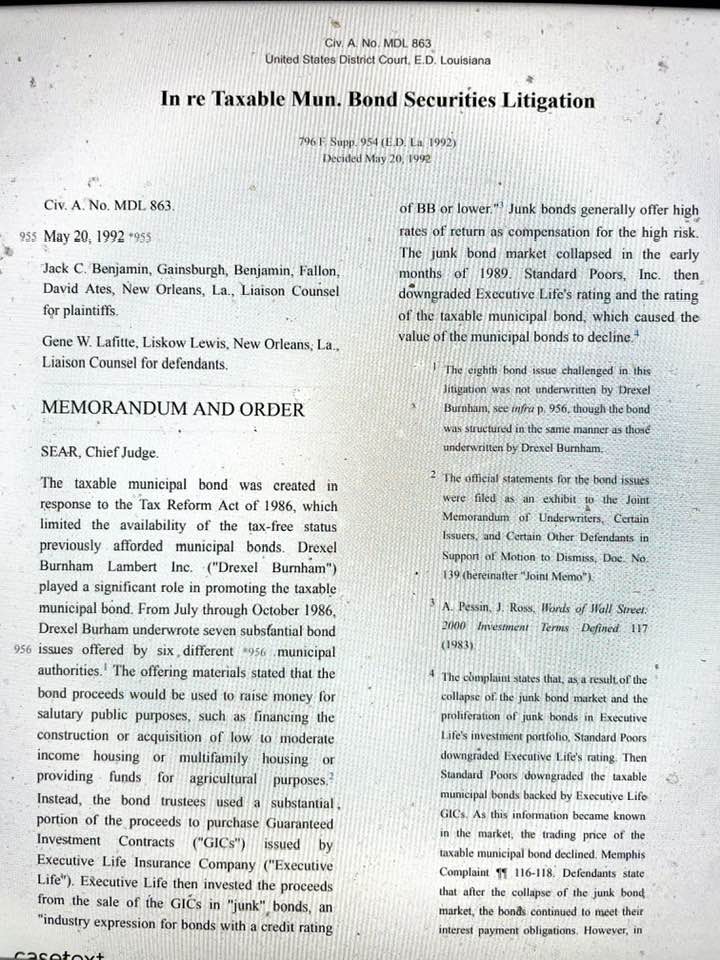

On occasion it was necessary for us to traipse down to New Orleans to attend court proceedings in the MDL (“multi-district class action case”), the massive litigation that ran parallel to our joint action against the receiver of ELIC. In the latter we were on the offensive; in the former, we were on defense. Between the two raging cases I found myself in a royal legal slugfest of a size and intensity I’d never experienced before (and never since). Our trustee-bank group, however, was only one corner of an even larger legal feeding trough. On a conference call toward the conclusion of it all, I remember Phillip Warden, our group counsel, informing us that the total legal fees paid out of the ELIC receivership exceeded $100 million.

Over the course of all the offensive and defensive wrangling, we reached a point where our group decided it would help the collective cause to meet with our bondholders. The very concept was fraught with danger and was anathema to trustees, who by training, experience, and the legal framework governing their actions, the most conservative personnel within a bank—outside of auditors, risk managers, and in-house lawyers advising the trustees. The evolution of the ELIC case, however, had led to extraordinary circumstances, and eventually a consensus among us that the risk we faced by hiding from bondholders outweighed the risk of meeting with them. We’d already been dragged into a class action over the ELIC meltdown, and even outside of that litigation many bondholders had become overly obstreperous. I say “overly,” but who could blame them? Their investments had turned to mush, and after years of hearing, “We’re working on it” from us trustees, not a cent of recovery had yet been distributed.

We trustees and our lawyers all agreed that any such meeting would have to be very carefully orchestrated and conducted with extreme care and effective controls. For example, after deciding that we’d have to allow for a Q and A session—surely the most dangerous part of the agenda, but not something we could avoid—we decided that one of us would have to be positioned to pull the cord on the microphone if any bondholder started shouting obscenities (a real possibility) or threats beyond the pale.

After a number of conference calls to discuss the bondholder meeting—our objective, the agenda, the location, and logistics—the question arose, “Which of us should lead the meeting?” Or more bluntly stated, “Who was going to be the prime target of rotten tomatoes, scalding water balloons, and potentially worse?” One of the lawyers said—perhaps out of self-interest spawned by fear—that it would be a mistake to have any of the outside lawyers (acting in the capacity of a lawyer) to chair the meeting. “One of the actual trustees,” he intoned, “should be in charge of the meeting.”

Thus far in our long string of marathon phone calls, I’d been the only corporate trust officer among the half-dozen trustee-banks involved who’d ever spoken. I’m not sure that whatever I’d said was particularly enlightened or memorable, but the fact that I’d said something now and again was definitely remembered. Before I had a chance to refuse or hesitate, someone else on the call moved to nominate me to lead the meeting. Several other lawyers seconded the motion immediately, and before I knew it—and before I could answer Tom Kimer’s question (with the mute button still activated), “You okay with this?”—by acclamation I found myself appointed to a most unenviable position.

The next step was to identify and secure a meeting site—make that two, the second being connected by the latest satellite-feed video conferencing technology, which was still in its infancy—and establish a time and provide for dissemination of a meeting notice.

After these basic steps had been taken, we agreed that our whole group of trustees and lawyers would all fly to Manhattan two days before the bondholder meeting. Our task would be to “get our act together” before showtime.

Tom Kimer shared my worries that agreement within our group on a unified “opening statement” to the bondholders we were attempting to assuage would a huge challenge. In Tom’s view we were officially either a herd of cats or free-range cattle—given the Texas contingency involved—he couldn’t decide which. Yet it would be I who would have to stand behind a lectern, call the meeting to order, then proceed to maintain order over the planned duration of 90 minutes.

Every job has its stress points. I’d certainly had my share, but I was now feeling pressure of a magnitude that for me was on a whole new scale. (Cont.)

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2024 by Eric Nilsson

[1] Executive Life had been rendered insolvent when its sizable portfolio of junk bonds—again, thanks to the salesmanship of the Junk Bond King—had tanked.

[2] During pheasant hunting—and wheat harvesting—season, Tom had joined some friends on a farm in South Dakota. After tiring of the hunt, Tom asked if he could ride shotgun on a combine. He was even allowed a stint at the controls. Over lunch the following week, Tom told me all about the latter adventure and said it beat hunting by country mile.