JULY 5, 2022 – (Cont.) “Against global standards of the day, our Constitution, adopted by all 13 Colonies in 1791 C.E., was an enlightened piece of political and governmental engineering. Few other countries back then had devised such a progressive framework of self-rule.

“As is the case when more than one human occupies a room, however, disagreements arose soon after the United States of America was formed. Former allies in the fight against Britain—leading Colonists such as Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson—became bitter political . . .”

“I’ve been meaning to ask where the name ‘America’ came from.”

The alien’s elementary question disrupted my thought cadence. I was about to describe the diatribes between Federalists and Jeffersonians when the alien was curious about . . . our name? Whatever. I’d been throwing a lot of information at the poor alien, and as smart as the creature was, every word and thought spilling off my tongue was completely foreign to this visitor from Goldilocks. I cut the alien some slack—I couldn’t imagine being on the receiving end of an explanation of life on its planet.

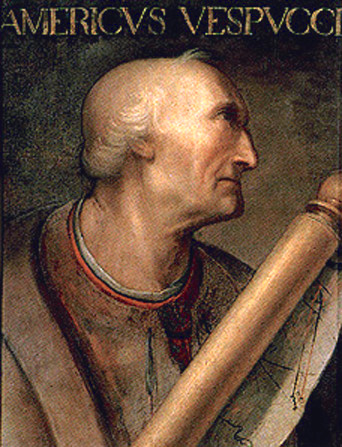

“’America’,” I said, “is an improbable label. It was derived from the first name of Amerigo Vespucci, a Florentine in the service of Lorenzo di Medici, who, in turn, was a leading member of the prominent banking and merchant family of Renaissance Florence. Signore Vespucci himself came from a well-established family, and without getting too far afield, between 1497 and 1507 C.E. he made several voyages with Spanish (including Columbus, Vespucci claimed) and Portuguese explorers to what Vespucci called, the New World. A contemporary German cartographer, Martin Waldseemüller, wanted to give Vespucci proper credit for the label, ‘New World,’ and did so by applying Latinized ‘Amerigo’—‘America’—to a new map of the New World. Other cartographers followed suit, and the name stuck for good—especially to the biggest country of this half of our planet, the United States of . . . America.”

“I see,” said the alien, as green and blue illumination coursed through its filaments.

“Now that I’ve satisfied your curiosity about the name . . . where was I?”

“Hamilton vs. Jefferson,” said the alien without missing a beat.

“Oh yes.

“This rivalry turned on opposing visions for the new country—the idea of a central bank, for example, commerce, manufacturing, and a strong central government, which was the Hamiltonian view, versus the ideal of a country dominated by bucolic agricultural life and planter-farmer-gentlemen left mostly to their own devices by small national government.

“As decades passed, however, two related developments occurred. First: the inexorable expansion of the nation westward. A whole, vast continent beckoned with limitless resources to be discovered, mined, hunted, and harvested, all for the insatiable acquisitiveness of the ‘rugged individual.’ Second was the contest for political power between ‘free states’ and ‘slave states.’ With territorial acquisition and newly formed states, this competition became more acute as the 1800s progressed.

“By 1860 C.E. free vs. slave became so divisive, the friction threatened to blow up the country. In the spring of 1861 C.E., Southern states seceded from the United States of America. This act of defiance sparked the bloodiest period of our history. No one living at the outset of the conflict could imagine the toll of the violence. The war didn’t end until four years later.”

“Who won?”

“That’s still being worked out,” I said. (Cont.)

(Remember to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.)

© 2022 by Eric Nilsson