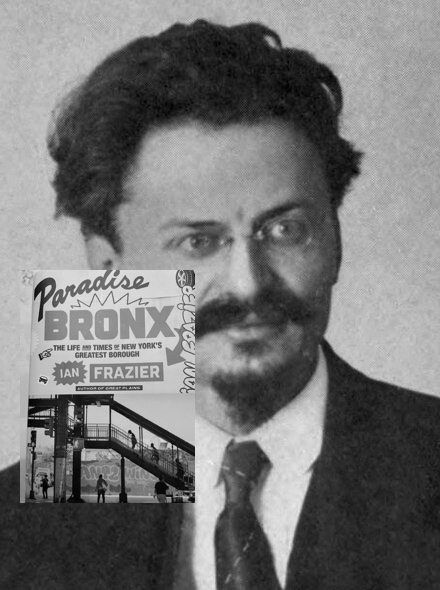

JANUARY 4, 2025 – (Cont.) Trotsky and his family arrived in the Bronx just as real estate development—mostly in the form of eminently affordable apartment buildings—was taking off. Thanks to extensions of cheap and easy public transportation from Manhattan, many residents of the crowded tenements of the Lower East Side who were employed in the Garment District, were relocating to the Bronx. (They knew how to find the Bronx on weekend excursions to the zoo, park and gardens.) For just 18 bucks a month, Trotsky was able to rent what he considered to be luxury accommodations. In his autobiography he wrote,

[The] apartment was equipped with all sorts of conveniences that we Europeans were quite unused to: electric lights, gas cooking-range, telephone automatic service-elevator, and even a chute for the garbage. These things completely won the boys [his sons Lev, 11 and Sergei, 9] over to New York. For a time the telephone was their main interest; we had not had this mysterious instrument either in Vienna or Paris.

For the next three months Trotsky gave lectures, wrote leftie polemics and made enemies of his fellow (American) extreme, radical, socialists—quite far to the left of today’s extreme, radical, socialist Democrats. In February (1917) meanwhile, Tsar Nicholas II abdicated and Trotsky and other rabble rousers, including Lenin, were allowed to return from exile. In March Trotsky and his family made arrangements for passage back to Mother Russia—and the mother of all repression, left, right and center.

Just before they were set to leave their apartment at 172nd Street, however, nine-year-old Sergei decided to satisfy his long-standing but unspoken curiosity: where was First Street? The kid made his way from the Bronx south into Manhattan and down a number of blocks but then inexplicably (given the grid layout of streets and avenues) lost his way. He inquired of the police, who—thanks to the telephone—contacted Sergei’s parents back at the apartment[1].

Ian Frazier—author of Paradise Bronx—laments the fact that despite Sergei’s temporary but untimely wanderlust, the family made their way to the ship in time to board it. “Would they had missed it!” writes Frazier. “Better by far if they had stayed in the new paradise Bronx, in their nice apartment with its affordable rent and modern conveniences.” He goes on to underscore the critical role Trotsky played in the run-up to the October Revolution. A few months after Trotsky’s return to Petrograd, Lenin got sideways with the Provisional Government (which had replaced the Tsarist regime), which pushed him back into exile (in Finland). Trotsky held down the fort, as it were, during Lenin’s absence. As Frazier notes, the Bolshevik Revolution would not have happened without Lenin, but Lenin would have had nothing to work with when he returned to Petrograd in October if Trotsky had not kept the party afloat since his own return early the previous spring.

In one of history’s greatest “what ifs,” Frazier ponders,

A million and a half Russian Jews came to New York; one Russian Jew going in the other direction helped immiserate half the world. What if Trotsky had stayed, and his kids had grown up happily in the paradise Bronx? The family could have become Babe Ruth fans and Russia [could have] avoided seventy-odd years of bloody despotism.

Frazier is no fan of Marxism-Leninism-Trotskyism. He closes out the chapter featuring Trotsky by recounting a classic anecdote about the doctrinaire revolutionary as told by Frazier’s friend, Roger Cohen, editor of Yale Environment 360, an online magazine.

As a young married couple, Cohen’s grandparents were among the Jewish migrants from the lower East Side of Manhattan to the Bronx. His grandfather got a job as a waiter at a Bronx restaurant frequented by Trotsky. Trotsky didn’t believe in tipping, however, because he thought the workers should be granted a fair wage without having to rely on tips. From a practical standpoint, that’s not how the wait staff saw it. The restaurant owner trying to make ends meet by paying market-rate hourly wages wasn’t about to increase wages because a dogmatic leftie expressed his politics by not leaving a tip. Accordingly, Trotsky got bad service. He retaliated by hogging his booth for an undue length of time (for a light lunch or lousy cup of coffee) to prevent revenue-generating customer turnover. The wait staff, in turn, gave him even worse service, leading to longer stays by Trotsky in a kind of “no-tip-for-tat” arms race.

Roger Cohen’s grandfather, however, bucked the tide “because,” reported Roger, “he thought everyone should be treated decently”—an attitude that transcended politics and adherence to any given economic theory. The grandfather gave Trotsky the same excellent service that was given any other customer. Trotsky responded by leaving the booth promptly after finishing his coffee, lunch, whatever. But he still left no tip (the Commie, pinko, leftie!).

With notable chuckle value, Frazier describes the result of some online research he conducted about Trotsky’s time in the Bronx. Apparently, Trotsky’s great “takeaway” (besides his impression of the luxurious apartment) was the whole tipping business. He was so dogmatic about it, he tried to persuade other diners not to tip. Then came the zinger from Frazier: “[O]ld Mr. Trotsky, just another New York City nut.”

Paradise lost in paradise Bronx.

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2025 by Eric Nilsson

[1] In a sad postscript, Sergei lived out his life in Russia. He trained as an engineer and worked at the Moscow Aviation Institute. He stayed as far away from politics as he could—even changing his last name to his mother’s maiden name (Sedov) to achieve a lower profile. But his efforts to distance himself from his father’s legacy (Stalin kicked Trotsky out of the Politburo in 1926, exiled him to Siberia in 1927, had him deported in 1929—and assassinated in 1940) came to naught. Sergei was eventually—inevitably, when he refused to betray his father—ensnared by Stalin’s Great Purge and killed in 1938, possibly earlier. Decades later Sergei’s daughter petitioned Gorbachev to rehabilitate her father, and in 1988, the request was granted. Too bad nine-year-old Sergei hadn’t kept walking all the way to lower Manhattan (with no need to contact the police) or hadn’t contacted the police when he did get lost or . . . too bad the Trotsky family apartment in the Bronx was equipped with a telephone to receive the call from the police. Under any of the foregoing alternatives, maybe Trotskys would have missed their scheduled passage back to Russia, and Trotsky would not have been able to return by other means in time to save the Bolsheviks for Lenin’s October putsch; in which case neither Trotsky nor Sergei would have died at the direction of Stalin!