JANUARY 3, 2025 – This morning I sent a New Year’s greeting to a close Czech friend of ours and life-long resident of Prague. He’s a heart surgeon by profession, but he could achieve worldwide fame if he converted his principal avocation, photography, into his primary vocation. In my applause responding to his latest round of photos—the full panel that comprised his family’s 2024 Xmas card assortment—I remarked that “By each of your well-crafted photos I see and learn something new about life on our paradoxical planet: infinitesimally tiny at the same time it’s infinitely enormous.” (emphasis added).

After hitting the send button, I closed my laptop and picked up the book previously mentioned on this blog—a volume through which progress has been exceedingly slow but exceptionally rewarding. Paradise Bronx, it’s called, with the subtitle, The Life and Times of New Yorks Greatest Borough by Ian Frazier. The 508-page work (plus 38 pages of notes) is packed with the fascinating history and contemporary life of the only part of New York City that isn’t an island or part of an island. Frazier is a superb writer and observer who loves taking his reader down innumerable intriguing rabbit holes.

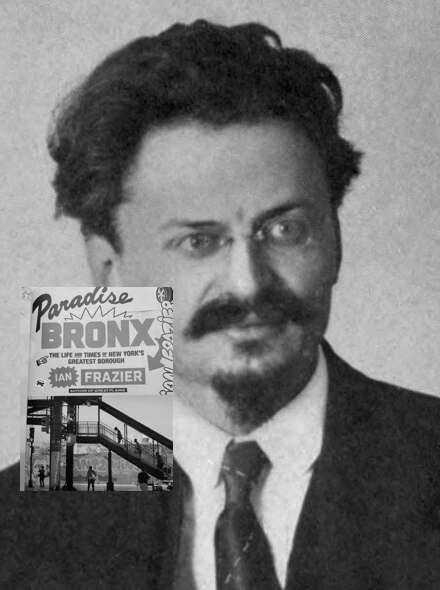

These side trips are so numerous and riveting that they are one reason my progress through the book is so slow. Among today’s “stops” was a series of anecdotes about Leon Trotsky’s life in the Bronx. Yes, that would be Leon Trotsky of the Bolshevik Revolution. As always, there’s a story behind the story behind the story. The details of Trotsky’s American sojourn reminded me of what I’d observed earlier this morning about our life aboard our “paradoxical planet”: At once insignificant and ginormous.

In the aftermath of the assassination of Tsar Alexander II in 1881 at the hands of revolutionaries, all hell broke loose against Jews in Russia. Several of the accused co-conspirators involved in the assassination plot were “rumored to be Jewish,” and thus, age-old anti-Semitism conspired with the equally old principle of guilt by association to unleash yet another major pogrom. This was all tragically ironic, for in a land as anti-Semitic as any other place on earth, the assassinated Tsar had initiated reforms that favored his Jewish subjects: he eliminated special taxes on Jews and graduates of secondary school were allowed to move outside the Pale of Settlement imposed by Catherine the Great. By imperial decree, Jews also became eligible for state employment. As a result, huge numbers of educated Jews moved from the Pale to Moscow, Saint Petersburg, and other big cities.

When Alexander III succeeded his father, the new Tsar slammed the brakes on accommodation of Russian Jews. Taking their cue from this reactionary policy, Russians went on a rampage against Jewish communities everywhere, killing, burning and pillaging thousands of people. The violence was stoked in part by a widely distributed hoax publication called, The Protocols of the Elders of Zion—purportedly created by the Tsar’s secret police—a precursor of the disinformation campaigns instigated by Tsar Putin and wrought by Russian internet bots. Many of the now impoverished survivors of the post-assassination pogroms decided to get the hell out of Dodge . . . er, hell. Between 1880 and 1910, nearly a million and a half of them landed in New York City; over a million stayed, while the others, in similar fashion to other ethnic groups, fanned out across America.

By 1917, of course, Tsar Nicholas II, son of Alexander III, was in the hot seat, fueled by rising revolutionary fervor in the capital, Petrograd (formerly the Germanic “Saint Petersburg,” until the outbreak of the Great War triggered anti-German sentiment). Before things boiled over, however, many of the leaders of various competing factions had been living (and fomenting revolution) in exile. Trotsky—born Lev Davidovich Bronstein of a wealthy Jewish family in Ukraine—and a repeat revolutionary offender had been exiled to Siberia in 1907. He managed to escape and find his way to Western Europe, where he lived and worked for the socialist upheaval of Russia. He eventually landed in France, where his anti-war activities led to his deportation to Spain, where he likewise became persona politicus non gratis and with his wife and their two sons, was deported via an outgoing ship headed for . . .

. . . New York City. Arriving on January 13, 1917, they were met at the pier by none other than a member of the Hebrew Sheltering and Immigrant Aid Society, which had helped so many other Jewish refugees from the Pale. Right off the bat, they rented an apartment in . . . the Bronx. (Cont.)

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2025 by Eric Nilsson