APRIL 17, 2023 – (Cont.) I hadn’t intended to watch the “making of” segment that automatically followed the final episode of Transatlantic, but after a couple of minutes’ worth, I was hooked. Having read a few books on filmmaking back when I naively thought (and did) write a screenplay, I had some inkling of a film’s myriad moving parts. Years had passed since my “filmmaking obsession,” however, and in the course of watching interviews with the actors, producers, directors, set organizers and cinematographers of the Netflix series, I recalled the many facets of cinema that are noticed but rarely fully appreciated by film-watchers. From concept to screening, a staggering amount of on-camera and off-camera work is required to make a film worth watching. What’s amazing is that we have thousands of films from which to choose. Scroll through the offerings of every streaming service, and you’re reminded of the endless inventory of film projects that involve a similar complex production process.

As I watched the “making of,” I thought of the triple wonder of any good film: the story, especially, as in Transatlantic, its basis is true; the means by which the story is told—that is, the screenplay, the actors, direction and all the things the viewer sees and hears; and the actual making of the film, which comprises countless details much in the nature of a 5,000 jigsaw puzzle, wherein the pieces have little to no cogency when scrambled across the table.

After pondering the film world I considered randomly other human endeavors, from medicine to engineering and architecture to commercial aviation to symphony orchestras to the acknowledgment of a million and one other arenas of complex systems. Two features are common to all of these: 1. A broad division of labor and input; and 2. Most of the complexity is unknown to consumers, and in most cases, unacknowledged and unappreciated even when—or to the extent—details are known.

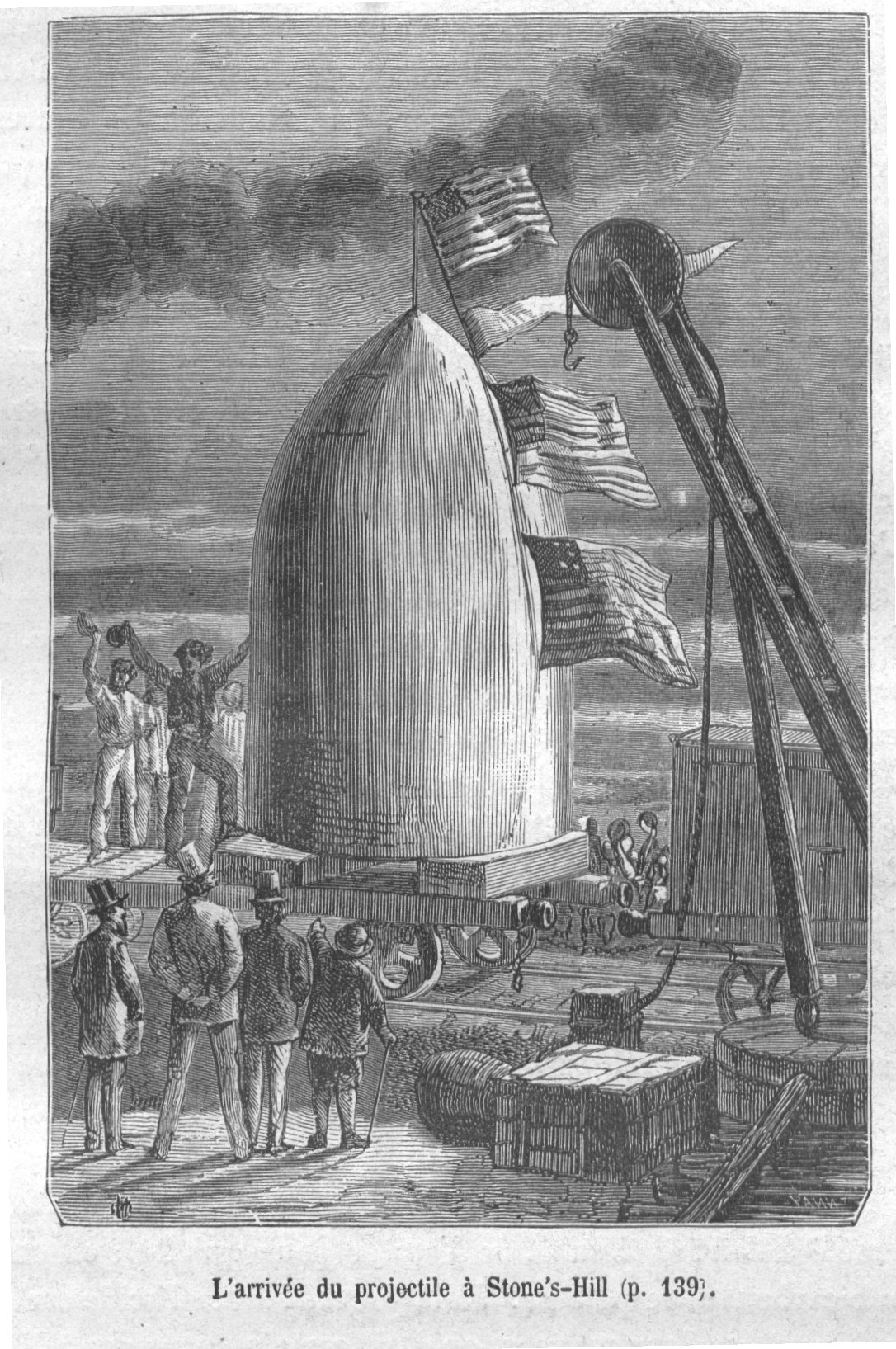

Advantages and disadvantages accompany this universe of complex (and ever amazing) systems. Travel, for example, is enhanced to a degree unimaginable by people before 1865 (the pub date of De la Terre à la Lune (From the Earth to the Moon) by Jules Verne), thanks to modern commercial aviation, but . . . you hope to hell your not on one of those amazing machines when one . . .crashes. Another example of the cost-benefit duality of amazing and amazingly complex endeavors is that countering the downside that none of us is self-reliant in much of anything, is the fact that we’re forced—often kicking and screaming—to work in concert with other human beings: If you’re wedded to the concept of complete self-reliance, good luck with performing open-heart surgery on yourself or playing Bruckner’s Symphony No. 7 as a solo on your piccolo.

Each of us plays some kind of critical role in the total network of “amazing stuff” in the world—even if that role is pure consumption, because in the absence of demand, whether it’s for a bridge, a museum, medical miracles, the produce section inside a grocery store or the New York Philharmonic performing . . . Anton Bruckner’s Seventh Symphony . . . or an evocative Netflix series called Transatlantic, without demand there’d be no supply. And of course, the “supply” of wonderful things requires legions of people dedicated to designing, funding, producing and distributing all that supply.

This perspective on “amazing stuff” was an unanticipated benefit of having watched Transatlantic . . . past the show itself.

(Remember to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.)

© 2023 by Eric Nilsson