FEBRUARY 24, 2025 – (Cont.) The fourth letter from February 1981 in the packet that Russ sent me exactly 44 years later was from (now) Dr. Pavel Šebesta, the inimitable Czech, to whom I introduced the readers in “Stage IV” (2/19/25 post) of this series.

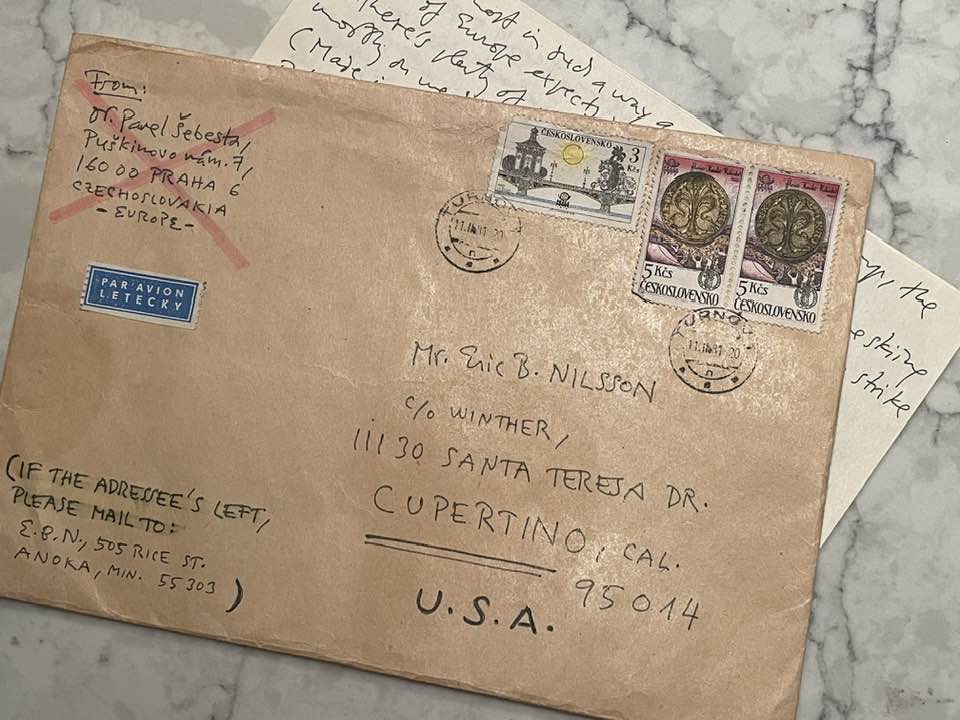

Pavel’s letter came in a large light brown envelope bearing his distinctive European handwriting, exotic “ČESKOSLOVENSKO” postage stamps, and “PAR AVION – LETECKY” sticker. Between our initial meeting in Delphi, Greece in June, 1979 and the arrival of his letter in Cupertino, California in February, 1981, we’d corresponded regularly, and I was always delighted when one of his letters arrived. I was always amazed, too, and never took for granted, that our letters were crossing both ways over the Iron Curtain. Moreover, our correspondence began more than a full decade before The Wall came down. The end of the Cold War and revision of the map of Europe seemed to be an impossibility—in our lifetime, anyway.

I remember Pavel commenting bitterly as late as the summer of 1987 about what he perceived to be the political reality to which his beloved country and culture were captive. He’d been allowed to travel to the United States to participate in a special post-doc cardiology-surgery study at the famous Ochsner Clinic in New Orleans. The Soviet regime, of course, had held his family hostage back behind “the Curtain.” That summer Pavel had managed to break away from New Orleans to visit us up in Minnesota. Among other places, we took him to Björnholm for several days. An avid outdoorsman (in addition to being highly urbane), Pavel was in his element. I remember distinctly canoeing with him way out on the lake. He enjoyed the voyage immensely, but inevitably, our animated conversation turned to politics. Pavel expressed his resentment of the regime back home and dictates of the Soviet overlords. He longed to be free but in despair acknowledged the realities of history and geography.

“What do you think of this guy Gorbachev?” I asked. “Doesn’t he signal a fundamental change in the direction of the Soviet Union?”

Pavel scoffed at the notion. “He’s still a Russian,” he said dismissively. “They’re all the same. We’ll never be free. Not in my lifetime, not in my children’s lifetime, not in my grandchildren’s lifetime. We’ll always be subject to Russian rule.”

I recalled my distress upon discovering after returning to my pension in Athens after that day in Delphi, that I’d lost Pavel’s address. He’d encouraged me to write despite the fact that our letters would be censored. Censored. The concept of censorship was starkly alien to me. When Pavel mentioned it, I realized what I took so for granted. Up to that point in our conversation back in Delphi, Pavel seemed so Western; so well informed about my world and what was going on in it. Apart from his Czech accent, Pavel could’ve said with perfect credibility that he had grown up in Madison, Wisconsin. The matter of censorship—of which he was keenly aware—is what revealed the huge gulf between our respective place of origin.

We had exchanged addresses, and in my despair over having lost his address was a glimmer of hope that Pavel would write to me. That hope rested on the assumption that his return address would appear on the outside of the envelope of his correspondence. The reader can imagine my mixed reactions of delight and disappointment when two or three weeks later, the mail would bring not a letter from “Čekoslovensko” but a post card—with no return address.

It was one of my great fortunes that Pavel would soon thereafter follow up with a letter—in an envelope containing his address. I was not, however, quite out of the woods: when it came to the name of his street, his European-style handwriting was not entirely legible. Using his penmanship in the letter itself—which provided sufficient context for deciphering (it worked as an analog to lip-reading when straining to hear someone in a loud venue)—I tried to decode the street name, but I remained unsure. Ultimately, I reasoned that it would be Czech postal workers on the receiving end, not their American counterparts at the sending point, who would need to read the street name. Accordingly, instead of risking an erroneous transliteration, I would simply mimic the best I could, Pavel’s hand-written street name.

The other day, with Pavel’s 44-year old letter and envelope in hand, I recalled that relief. I examined closely the return address: “Puškinovo Nám. [abbreviation for “Square”] 7.” It was to become eminently familiar to me over the next two years—and long thereafter, of course—as our correspondence flourished. What surprises me—to the point of embarrassment, really—is that until just now, the “inovo” in “Puškinovo” obscured the obvious, “Puškin,” as in “Pushkin,” as in “Alexander Pushkin,” perhaps the greatest poet Russia has ever produced and ever will. I now need to ask Pavel, whose education and family tradition are steeped in language and literature but whose visceral dislike of the Russians is often and openly expressed, how he felt about his street’s name—labeled after a great Russian poet.

One of the highlights of my Grand Odyssey would be my extended stay with Pavel and his first wife, Magda, in Prague, sharing meals with their extended families, and meeting their circle of friends. Even the most casual observer could see that these people were among the elite of the country’s artists and intelligentsia—and, it went without saying, critics of the Communist regime.

Pavel’s letter anticipated my visit—still four months away.

February 10th

Dear Eric,

I only hope this letter will catch you in time before your romantic escape to beaches, mountains, and icebergs of New Zealand [. . .]

Eric, you picked the finest time to visit Prague. Just let me know ahead about your definite time of arrival so I can look after necessary affairs. By the way, our good family friend (a woman about 55), who normally offers her Prague flat to our common friends arriving from abroad, looks forward to her prospective lodger almost in such a way as we do. So hurry up. The Heart of Europe expects you!

[. . . ]

Good luck & best wishes,

Pavel

The letter and envelope appeared as fresh as they had the day I’d received them the first time in late February 44 years ago. Pursuant to a letter I’d sent to Pavel in late January telling him of my upcoming whereabouts before leaving on my travels abroad, he’d addressed the envelope to me “c/o Winther” at their Cupertino address. In the lower lefthand corner, however, parenthetically, he’d neatly printed (for my (American) hosts and American postal workers),

(IF THE ADDRESSEE’S LEFT,

PLEASE MAIL TO:

E.B.N., 505 Rice St.

Anoka, Min. 55303)

As it turned out, I hadn’t yet left the country. But 44 years later, Russ—grandson/nephew of my hosts—would, in fact, mail the letter back to Minnesota.

I smiled at the symbolism of the “Grand Odyssey” of Pavel’s letter. To complete the circle, however, without further ado, I sent an email to Pavel. After explaining the recent background to reappearance of his letter, I reflected on what would become the theme of this series . . .

This morning when I re-opened that well-preserved envelope from Praha and the past, I felt as if I were the Time Traveler in the classic story by H.G. Wells. The pages bearing your script (and that of your “editor”) [Pavel’s first wife, Magda, a Czech screen actress, spoke and wrote impeccable English; for a while she’d served as President Vaclav Havel’s personal English tutor] were as fresh as they had been exactly 44 years ago yesterday.

What an image—actual and figurative—this scene conjured! A letter from one inveterate traveler to another, re-crossing the bridge of time, stirring to life so much that has accumulated aboard our respective caravans along the main routes and innumerable side trips of a period longer than what had separated us in 1981 from the close of World War II!

One of my many reactions to your remarkable letter was an ostensibly off-handed but in fact, very intentional and significant (for the times) mention that you were writing from “the heart of Europe.” Though I was a largely ignorant American of that day . . . thanks to my family, who were generally quite well informed of world geography, and consequently, my own interest in it from a very young age, I knew of the basic location of Czechoslovakia; that it had been born out of the Treaty of Versailles; that after two decades of prosperity, it was cut loose by the West, conquered by the Nazis, then the Communists. What I didn’t know or begin to appreciate, however, was the central place and role of Praha in the annals of European history; the deep, deep cultural richness of the Czechs. It was you, my friend, who threw open the doors and windows–not for the purpose of defenestration, so favored by the villains, but for my personal edification and enrichment. It was you who put Praha’s place on the map—at the very center, the very heart of Europe.

The world, my friend, and life, are things of miraculous beauty, accentuated by all the horrific pain, evil and suffering that accompany the good.

The Time Machine was now resting firmly back in the present. The datometer was still. Yet no matter where the machine might be parked—past, present or future—time itself never stops. As a friend recently described time, “It’s like a stream of water passing between your fingers but never stopping.” Thus doth time evade our grasp and control, which is why memories are held so dear.

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2025 by Eric Nilsson