APRIL 4, 2024 – (Cont.) The crazy thing was that at around this same time, Dad bought another 120 acres of similar land near the scruffy town of Zimmerman deep into the next county. To get there we had to drive through Elk River, the county of seat of Sherburne County, and past the first rural nuclear power plant in America. Dad always pointed out both the power plant and Elk River’s special standing.

At what he called the “Zimmerman tree farm” he’d hired another local tree farmer to plant 20,000 white pine. Dad took me on periodic trips there to check on progress. He’d obviously had a similarly contradictory plan for that crop of “Christmas” trees. What drove him silly, however, and fed his nascent anti-government slant was the federal government’s condemnation of the land. The Department of the Interior had hatched the “hare-brained” (according to Dad) idea of establishing a “natural prairie” preserve wherein the land would be returned to its original state before German and Scandinavian farmer-immigrants had invaded. The trees that Dad had planted—and that the government had subsidized—were now to be cut down by the same “big, bad wolf,” namely, the federal government.

When the deed arrived for Dad to execute, he wrote back and demanded the extra “one dollar ($1.00)” of stated consideration that as far as Dad was concerned, had not been included in the condemnation award. He thought he was being clever in expressing his displeasure with “big government.” When he explained it all to me, I too thought he was being clever. In retrospect, I wonder about the origins of his strange ideas about government always being “the problem”—given that his + 30-year career had been as a government official.

Invariably, Dad worked hard on our tree farm trips. In the trunk he ferried saws, pruning shears, an axe, gopher traps, gopher poison, and heavy work gloves. While I wandered about, he went on gopher patrol, trimmed and thinned the trees, and after he purchased the additional land north of town from Ray Chase, he pruned the scraggly red oaks.

He envisioned a kind of tree park, though for what particular purpose I don’t know. Given the nature of his day job, heavy on paper and people, I think Dad simply needed an outlet among . . . the trees. Dad was an artist in the fullest sense of the word, and he viewed trees much as a sculptor might regard a block of marble. He could envision how a tree could be shaped and enhanced, and he’d studied much and experimented lots, the art and science of arbor pruning and cultivation. It didn’t much matter that his “sculpture garden” would be hidden in the back corner of a strip of rural land that no one except he—and I, and maybe one of my sisters—would ever lay eyes on. I don’t remember that Mother ever accompanied us to Dad’s “church”—but then again, until Mother finally converted Dad (after I’d been sent away to school), Dad never attended Mother’s house of worship.

Occasionally a trip to the tree farm would involve added excitement beyond Dad’s routine. Setting fire to a brush pile was one such example. Why he thought it was necessary to do this wasn’t entirely clear to me. Or why he thought it was a worthy subject of a home 8 mm movie, except that it happened to coincide with a rare visit by Grandpa, who, with a lit cigar in his mouth, would help drag dead oak branches over to the crackling arbor pyre.

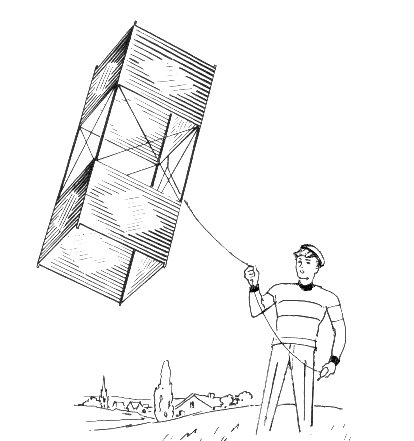

When the Norways were still in the seedling stage, the land was ideal for kite-flying. For a time, Dad embraced the fun, and kites became high-flyers when he was at the controls. I remember when we upgraded to a box kite, and Dad replaced the cheap plastic string holder that came in the kite package with a foot-long section that he sawed off an old broom handle. He then wrapped what seemed like half a mile of nylon string around it and tied the loose end to the kite. Dad flew it so high above the Norways, we could barely see it.

Then there was the Sunday when we took visitors out to the tree farm—our neighbors down the block, Lyle Roeckers and his son John, a grade ahead of me. Lyle was a pheasant hunter and owned guns. For fun, Lyle talked Dad into shooting clay pigeons, and what better place to do that than at the tree farm?

While the men took turns slinging the clay disks skyward and shooting them down, John and I were given a .410 shotgun to play with[1]. Well, not exactly play with. The shotgun, we were told, was never, ever to be pointed anywhere close to any of us or any other human being that might emerge from the woods or plop down out of the sky. For target practice, Dad had brought the Sunday paper, pages of which he stuck onto a brush pile. I remember taking aim at the colorful funnies section, and according to Lyle’s careful instruction, putting the shotgun butt up to my shoulder, taking aim and pulling the trigger. Upon inspecting the target, I was impressed by the million and one holes that I’d shot into the worlds of Dondi, Dennis the Menace, and Winnie Winkle. (Cont.)

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2024 by Eric Nilsson

[1] For being a non-hunter and non-owner of guns, Dad proved himself to be an excellent shot. After just a few tries, he got the hang of it and blasted to bits one clay pigeon after another. Perhaps that was why Lyle felt comfortable loaning Dad the .410 so Dad could “take out” the woodchuck that lived in our next-door neighbors’ backyard and dined on Mother’s flower garden near the boundary. After work one day, Dad in fact did “take out” the flower thief.