JUNE 30, 2024 – Old age. It’s on the table, and we need to talk about it. Efforts to convince Joe Biden that he should retire from the ticket remind me of a family’s decision to take the car keys away from “dad,” when he thinks he’s still perfectly fit to drive. “I might not drive as fast as I used to,” says dad, “and I might not be able to turn my head as far as I used to, but I know one thing: I know that a green light means GO, and I’m still rarin’ to go.”

And that’s a problem. But how to convince someone that the speed of their synapses falls short of their desire and confidence, at least when it comes to making split second decisions behind the wheel?

I’m trying to put myself in the position of “dad” so that I can better understand “him” (i.e. an elderly presidential candidate or any of my aging friends and family members), but also to ensure that I hand over my own keys before someone asks or tells me to do so. “Keys,” of course, stands for various rights, privileges, and potentially dangerous activities besides driving a motor vehicle.

Up at the cabin I’m already more cautious than I used to be. I’m no longer as quick or strong as I once was and not even that many years ago. Moreover, I’m more cognizant of the million ways to hurt yourself in the course of DYI cabin projects, in some cases rather severely, if you don’t think things through.

Today, as part of our cabin grounds improvement program, I identified among the trees along the side of the yard, a 30-foot-high, six-inch-wide trunk (at the base) white pine that had recently died. Most trees in the wild that die should be left standing, since they fill several critical post mortem roles, but the tree in question is also close to the fire pit, and drained of life, the trunk and branches are ready tinder for errant sparks. Plus, from an aesthetic perspective, the dead tree detracts from the “scene.” I surveyed tree and site and was confident I could fell the tree without doing any damage—to myself or the grounds, though one garden was close to where the top of the tree would land.

I then pulled out my . . . chain saw. Chain saws have always made me nervous. The most dangerous element, of course, is the chain itself. If it’s too tight or too loose, bad things can happen. But other aspects are what produce a plethora of added risks: a poor grip, bad footing, poor bar placement, flying chips, the tree landing on your head. Thus, you take precautions—you wear gloves, boots, chaps, helmet, safety glasses, keep both feet squarely on the ground, give yourself an escape route, and so on. I have added rules for my electric chain saw: Except when I’m getting ready to make a cut, I keep the safety bar on, and when I’m not on site, I disengage the battery.

In the end, however, I didn’t use the chain saw. The limiting factor was having no measurable margin of error as to where the top of the tree would land. There was the potential for it to land on two of the most glorious flowers of the garden—hollyhocks. Sure, I could notch/cut higher up on the trunk, thus creating a higher bottom and shorter hypotenuse of the triangle consisting of the ground, the portion of the tree above the cut and the stump below the cut, but I did not want to take the risk of having to explain why I destroyed those flowers.

After putting the chain saw away, I pulled out the pole saw to remove as many of the branches of the dead tree as possible. It sounds like a simple operation, and in large part it was, but limb cutting requires alertness and quick reflexes. Once your cut reaches the “hinge point” and the remaining fibers can no longer hold up the weight of the branch, the branch swings down—rather swiftly—and either drops straight to the ground or hangs, dangling “by a thread” like the sword of Damocles, and then drops without precise warning. In either case, you must have an escape route and be quick enough to step out of the way before the falling branch knocks you for a loop.

So far, so good. I’d put the chain saw back without using it—a bit like “dad” putting the keys in his pocket but for reasons unrelated to his compromised driving skills. I’d then sawed off four tiers of branches without having to bob or weave to safety—like “dad” walking, instead of driving, to the grocery store, pressing the “WALK” buttons and using the crosswalks along the way.

Confident in my skills and caution, I looked around for other tree trimming challenges. Ah yes! The large dead oak branch among the many live ones of the wondrous arboreal parasol that reaches out over three-quarters of our new dock! I adjusted the pole saw, took stock of my position on the dock, then put the saw in position and began the cut.

Halfway through the cut, the limb swung down, as I’d expected. Now it was truly a sword of Damocles, twisting in the slight breeze. I then realized I’d created a problem. My escape route was restricted to the width of the dock, unless I was prepared to leap off the narrow platform and into the water, slide on the submerged rocks, fall and knock myself out. Under no circumstance could I leave the limb hanging, but there it hung while I backed away to assess my predicament.

I could readily see what could go wrong: once I cut through the thin fibrous hinge at the point of the saw cut, the branch would drop straight down. The end would strike the dock and most likely break off, but I had no way to predict which way the “hilt” of the sword would fall—away from me or toward me. I felt a bit like “dad” anticipating his entrance onto the high-traffic freeway. Would oncoming cars and trucks have room to change lanes and if they could make room, would they? Would “dad” have the reflexes to calibrate his acceleration and if necessary, deceleration, then rapid acceleration again to make his way safely into traffic and not into serious trouble?

In the end, I took precautions, extending the pole as far as I could to maximize my distance from the dangling sword. I then took another look at my only escape route—the dock—and reminded myself that no matter where the branch fell, I shouldn’t wait but dash off the dock the split nano-second that the limb separated from the trunk.

I survived without a scratch, but as I cleaned up the fallen branch and debris, I asked myself, When are you going to know that you shouldn’t be doing this sort of thing? And apart from knowing when you should stop, when should you just plain stop before someone—namely you—gets hurt? Tomorrow? Next month? Next year? Three after that? A decade from now? What about driving? What about . . . practicing law?

There is no right answer until there’s a wrong result. Until then, there’s only good judgment.

* * *

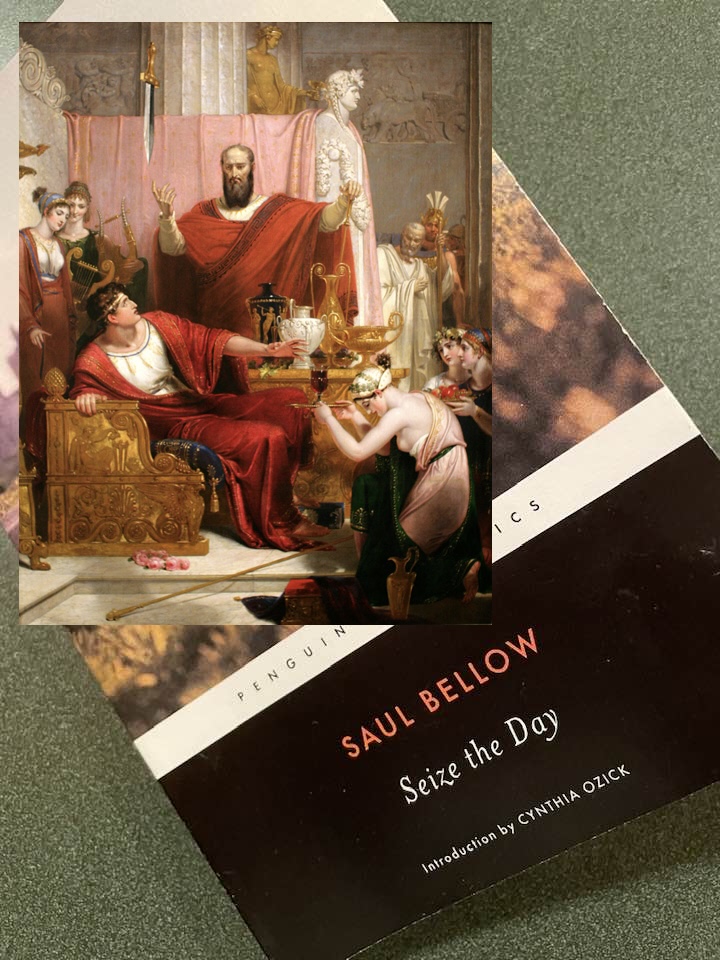

Later I put work aside in favor of some leisure time. The plan was to plant a chair at the end of the dock, lay a cushion on it, grab a snack, some water and my book club book, Seize the Day by Saul Bellow. After having plowed through an 800-page tome for our previous book, we went with Bellow’s lightweight 114-page novella. As matters turned out, the book could’ve used more heft. While I was arranging my stuff on the dock, a gust blew in from the west. It lifted all 114 pages plus the cover and the 23-page introduction of Seize the Day straight off the chair and . . .

With no time for thought, only reflex, I lunged forward and caught the book underfoot just as it slid in the gust to the very edge of the dock. If I’m too old to seize the day, at least I’m still quick enough to seize the book. Darn good book too; worth seizing if you have the chance—and the reflexes.

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2024 by Eric Nilsson