NOVEMBER 5, 2023 –

“A FAREWELL TO A GENTLE SWEDE” – ST. PAUL, MINNESOTA – MAY 12 – 14, 2010

The big, white, stately house graces the east end of Summit Avenue, not far from the St. Paul Cathedral and the James J. Hill Mansion. Inside, the house is spacious, well-crafted and well-appointed but by no means ostentatious. Books abound. Garrison’s study is near the side entrance—the only entrance that anyone uses, except during the periodic Democratic fund-raising events held at the house.

The study looks cluttered, but it is not so much cluttered as it is transitory, like a traveler’s suitcase after a week away from home. A discarded printer sits in the shipping box of its replacement. A letter from E. B. White to Garrison, preserved in a nice frame hangs on one wall and a large, old photograph of Garrison’s country grade school hangs on another. For years a number of other framed pictures lying around the room have been ready for hanging but never hung. A modest size desk is laden with stuff—a tea cup, a spare set of reading glasses, a box of pens, a pair of scissors, a couple of old magazines, a small pile of books, a couple of reams of paper for the printer—none of which looks as if it would be missed if it went missing.

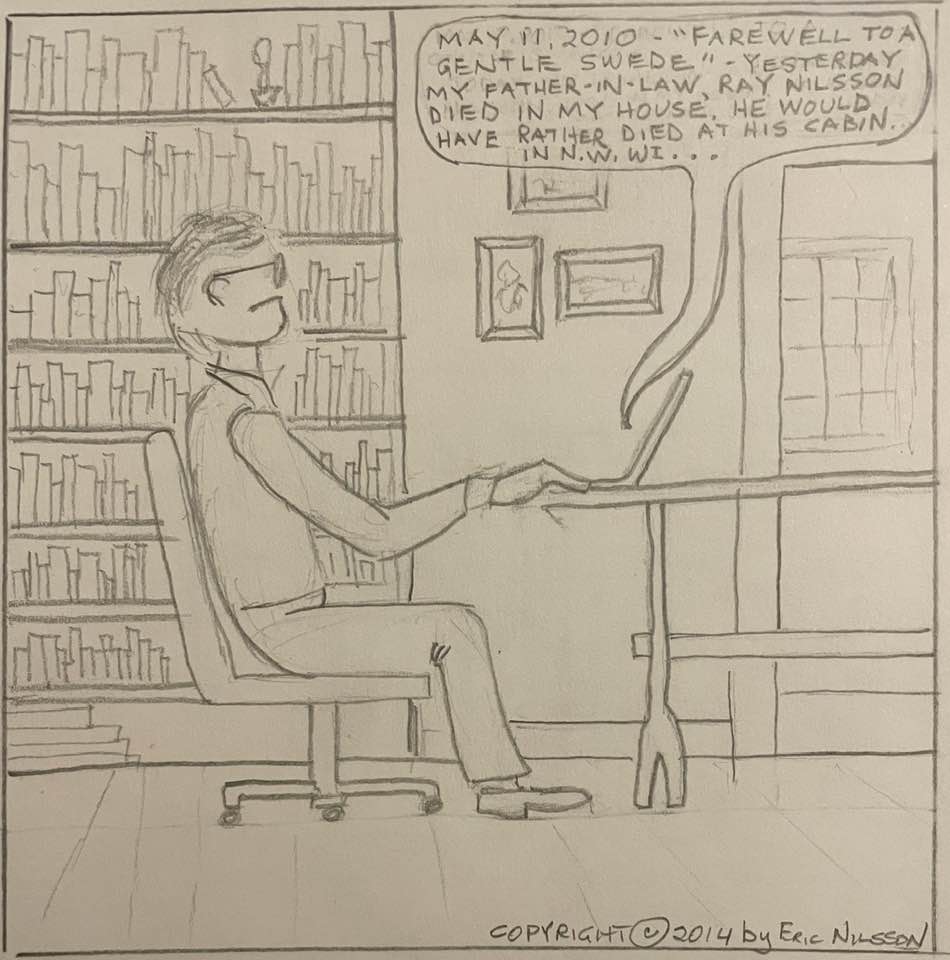

For all his fame as the decades-long host of A Prairie Home Companion on public radio, Garrison, I know, considers himself first and foremost a writer. By education, disposition, and raw volume of output, he is a writer above all else. While the rest of us openly mourned Dad’s death, Garrison wrote about it quietly. I imagine him sitting in his dimly lit study, the glow of his laptop screen reflecting off his eyeglasses as he tapped away. Garrison’s tribute to Dad was syndicated in newspapers around the world, including America’s newspaper of record, The New York Times. The piece was entitled, “A Farewell to a Gentle Swede.”

Mr. Ray Nilsson died in an upstairs bedroom in my house early Monday morning around 2:35 a.m., which was nothing he or I contemplated back when I married his daughter, but life takes us down some mighty interesting roads. If he’d had his choice, he probably would’ve died in the woods around his log cabin in Wisconsin, axe in hand, splitting wood — a big whump in the chest and the sky spins and you fall off the planet — or in his library, reading American history and listening to Schubert, or maybe in Sweden, walking around and listening to the beautiful language of his mother and whump get run over by a Volvo.

It was cruel, the last hand that life dealt him, multiple myeloma, months of veering wildly between excruciating pain and drugged stupor, and so it was a blessing when at 2:35, he simply drew a long breath and then not another one. He was 10 days shy of his 88th birthday. His caregiver, a beautiful man from Tanzania, an African prince named Al, called us and we ran into the bedroom and Ray lay on his side, eyes closed. There was loud weeping, distraught phone calls, more weeping, embracing, and my wife put on a CD and the room was filled with a Schubert mass, and around 5:30 the men from the mortuary arrived and took Ray’s body away, and at 7:10 I drove my 12-year-old daughter to school.

She liked to go visit her grandpa in the bedroom, and she was informed of his death, but she loves to get to school early so she can tear around in the gym and shoot baskets with other kids, and that was more important than death. I believe Ray shared that view. All of the rest of us felt the enormity of death, but the dead man and the little girl shared a disregard for the business of mourning and went off to other things.

He was a gentle Swede, an orderly man, a man of powerful memory who could recall exactly how he had gone about laying the concrete steps at his cabin 30 years before and recall this in such excruciating detail that you wanted to jump out the window. He wrote a wonderful memoir of all the cars he had owned (which, of course, he called his Auto-Biography). He could remember the day when, as an infant, he took his first steps — he really could — and he could remember every moment of that afternoon when a beautiful young woman from New Jersey had come knocking at the door of his parents’ rooming house in Minneapolis, looking for a room for her brother, and something electric passed between them, which led to a long loving marriage.

He made his living as the clerk of district court, and left it with no regret to embark on a long and happy retirement, walking two miles a day, reading history hour after hour, listening to Beethoven and Schubert and Bach, cutting wood, writing the history of his family. I came into his family late and was too busy to get to know him well, but I saw him clearly one fall day at his cabin when my wife begged me to please tell him not to go up on the roof. He was 80 and he had put a ladder up to go sweep leaves out of the gutters. I didn’t know how to tell Ray what not to do, so I simply climbed up on the roof with him and helped clean the gutters, which made me queasy, the sight of the ground far below, the fearful faces of women looking up, and the old man striding along the edge of the precipice. He was a tall taciturn man who, had you passed him on the street, you wouldn’t have noticed, but what an excellent life he lived until the killer came tiptoeing into the room.

I suppose there is no good way to die, but Ray made the best of his. He resisted painkillers to the best of his ability, wanting to keep his mind clear. He expressed satisfaction with his life. He showed his vast love of his four children and his wife. And throughout his misery, he said “Thank you” over and over and over. Those were the last words he said, two days before he expired

If Dad had read that tribute, he would have allowed himself a small modicum of amusement—a soft laugh much as he would have expressed reaction to a mildly funny birthday card. He would not have beamed with pride nor would he have broadcast Garrison’s column, except, perhaps to one of his cousins in Sweden with whom he communicated regularly. Dad was not into self-aggrandizement nor did he ever seek a hint of adulation or commendation. What he cared about was quality, whether it was in his own work or in the work of someone else. As amused as Dad might have been by the world-wide circulation of Garrison’s tribute, Dad would have focused mainly on the quality of the writing.

The funeral was held the day after the piece was published. Heavy rain fell most of that bleak day. On the drive to the church, I confided in my sons that I wasn’t sure I’d be able to deliver the eulogy without breaking down. I asked them for advice. Byron told me to take five deep breaths just beforehand. It was good, pragmatic advice—exactly the kind Dad would give. Cory then said I was asking the wrong question. “Why are you worried about breaking down?” he said. “It just shows you’re human.” That too is exactly the kind of thing Dad would have said, at least in his later years.

The day after the funeral, the skies cleared and the sun burst forth. In the late morning, the family, including Long and Thuan, gathered out at Acacia Cemetery right across the Minnesota River from the Twin Cities International Airport. Though just a short drive from the center of Minneapolis and the middle of St. Paul, Acacia is in a country setting. Sprawling down long sloping terrain, it is a beautiful site, with well-maintained grass, a nice variety of trees and commanding views of the surroundings. Devoid of ponderous gravestones—each burial site is marked by a bronze plate at ground level—Acacia looks more like a landscaped park than a burial ground.

We had Dad’s body cremated, and a portion of his ashes were to be buried next to his parents’ graves. Once we were all gathered around the pre-dug hole, the funeral home director handed me the simple wooden box containing the ashes. My job then was to place the box into the hole. I knelt down on the grass to do so, but when I began lowering the box, I was overcome with emotion. If the day before I’d managed to take five breaths, get up in front of several hundred people and deliver the eulogy without breaking down, as I committed Dad’s ashes to a shallow hole in the earth, no amount of breaths could prevent my tears. They washed over the box just as yesterday’s rain had washed over the landscape. I realized how much I loved Dad and how much I would miss him.

But that had not always been the case.

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2023 by Eric Nilsson

1 Comment

A very nice tribute. Thx.

Comments are closed.