NOVEMBER 6, 2023 –

THE LETTER – ANOKA, MINNESOTA – JUNE 17, 2010

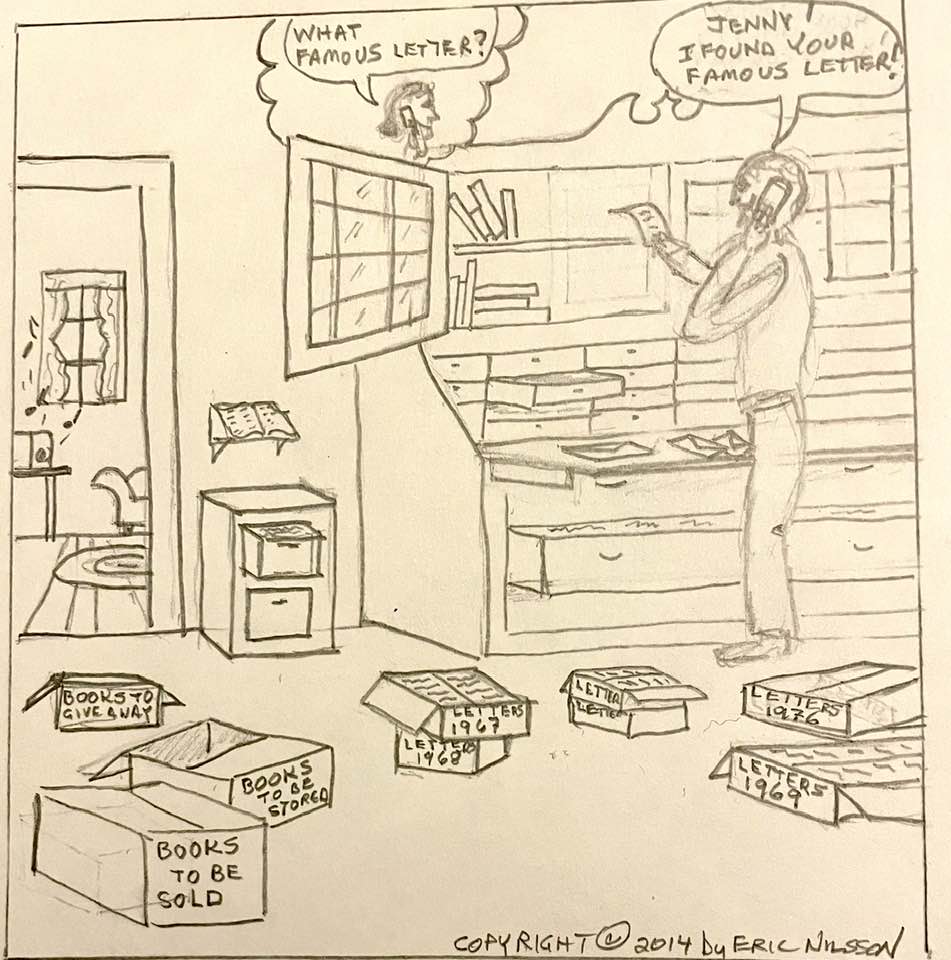

For nearly a month, I had followed the same routine. After work and a quick supper, I’d drive up to Anoka and spend a minimum of two hours going through the volumes of stuff that Mother and Dad had accumulated over the half century they’d inhabited their three-story colonial. On some evenings I’d hit a mother lode of interesting things, in which case I’d lose all sense of time and wind up staying until well past midnight. On weekends, I’d spend whole days sifting through papers, letters, notebooks, photographs, box-loads—even trunk-loads—of old mementoes, vast collections of one thing or another, and a lot of clippings, newspapers, magazines, empty containers, old videotapes of PBS programs, and hundreds of Easter Seal and Christmas Seal return address labels, much of which eventually filled the 30-yard dumpster I’d had dropped off in the driveway. Hoarding ran in the family—both sides—but Dad’s version was better organized than Mother’s. The entire project of sifting, sorting, saving and disposing would take me nearly 12 months of almost daily effort.

Anoka, the county seat, is an old river town that straddles the Rum River at its confluence with the Mississippi, about 20 miles upstream from Minneapolis. Settled in the 1840s, it began as a lumber town, centered on the harvests of logging operations farther north on the Rum.

Our family moved to Anoka soon after I was born. Exactly two days before I came into the world, Dad had been appointed Clerk of Court for Anoka County, and as was perfectly befitting, he and Mother purchased the old, two-story house that had belonged to a predecessor clerk of court. It was a cozy home with curb appeal and occupied a big, corner lot toward the end of Rice Street, which ran along the Mississippi River on the west side of the Rum River. But by the time Jenny came along three years after me, my parents felt cramped. Beckoning next door was a large, overgrown, vacant lot. In early 1960, Mother and Dad bought the lot.

In the evenings after supper, my parents would sit at a table out on the back porch of their corner lot house, pore over blueprints of their dream house and discuss desired changes. Colonial in style, its main feature was space—lots of it. The basement would extend under the garage and double as a bomb shelter in the event of nuclear war with the Russians. We’d have four spacious bedrooms instead of three cramped ones, and as the only boy—the “crown prince,” as Grandpa Nilsson would call me when just the three of us “men” were together—I would have my own. The “attic” would actually be a full, unfinished floor to serve as ample storage space for all the stuff Mother and Dad had already accumulated and for the volumes more that they anticipated.

Construction began in the fall of 1960. Since the courthouse where Dad worked was only a mile from our end of Rice Street, he often came home at noon to inspect construction, and, after work he spent more time going over things with his sense of perfection. Often his inspections would lead to conversations with—and corrections by—the contractor. Dad was a saver and never a debtor. He paid cash for the entire cost of the house. We moved in during August 1961.

Dad’s last day in his dream house was on March 23, 2010, the day he fell and couldn’t get up. By that time the yet-to-be-diagnosed disease had taken its toll. We moved Mother, who had her own issues, to an assisted living facility soon thereafter.

* * *

Beginning in May 2010, soon after Dad died, my routine varied little. I’d pull into the driveway and let myself in through the front entrance. I’d then step into the living room on my left and turn on the CD player. Dad’s collection of classical music was exhaustive, and for each of my sessions I’d explore deeper into his library. I turned up the volume commensurate with the distance my intended work area would be from the living room. More than once a piece brought back such strong memories of Dad, I could feel his presence in the room. The recordings that seemed to channel his spirit right smack dab to my side were the Atlanta Symphony and the Robert Shaw Chorale performing the Credo from Schubert’s Mass in G, one of Dad’s favorite works; Rubinstein playing Chopin Etudes or Beethoven’s Pathetique, one of the pieces that Dad himself played magnificently on the piano in the house or up at Björnholm, and . . . Jussi Björling, the legendary Swedish tenor, singing anything. And more than once I’d sit down and cry my eyes out over the reality that Dad was dead, gone, finished. Then I’d resume the task of sifting, sorting, saving and disposing.

I started in the attic. It was so wide, long and high that over the years anything and everything that needed to be moved to make space for new stuff got carried up to the attic. In the late 1960s, a couple of years after my grandmother had died, Dad moved Grandpa Nilsson from his big house near the Minneapolis campus of the U of M and moved most of my grandparents’ stuff to our attic. As I waded into things, I soon realized that I was taking inventory of not only a half-century but a full century of accumulation.

Overwhelmed at first, I resorted to an approach inspired by an old college friend with whom I’d long been out of touch. As an undergraduate, he was a star hockey player on our school’s championship team. He went on to become a PhD archeologist and oversaw an Etruscan dig outside of Sienna, Italy. One summer while traveling around Europe, I paid him a visit. The former athlete cut the perfect image of an Indiana Jones. For a day I watched him instruct his Italian work crew on how to mark off the part of a site that he expected to yield some worthy finds. The site did produce a significant discovery, and I was impressed by my friend’s use of a matrix and meticulous recording and drawing of bits and pieces that trowel and brushwork revealed.

I adapted some of those methods to the attic of my parents’ house. If, as it was turning out, disposition of the house and its contents had become my responsibility, I knew that apart from my basic duty to account to my sisters, they would be just plain curious about what I uncovered. Though Jenny and Elsa lived near me, they found it hard to plunge into such an overwhelming archeological dig. Our oldest sister, Kristina, lived in Boston and couldn’t participate even if she’d wanted to. I took lots of photos as I progressed and shared them with my sisters.

Our parents were not only big hoarders. They were also big-time writers, and in Dad’s case, a big-time archivist. As Clerk of Court, he had found a perfect vocational calling, for apart from all the day-to-day challenges of dealing with often fickle and quirky judges (according to Dad’s detailed accounts over the family dinner table), ignorant county commissioners (more stories over dinner), demanding public (still more anecdotes) and employee issues (we learned who the stars were—and which employees weren’t), Dad’s job boiled down to record-keeping—vital statistics and court filings.

In that big house on Rice Street I discovered what an archivist Dad had been inside and outside of his job. His organizational proclivity was sprinkled with humor. One evening while going through a shelf-load of boxes stuffed with personal files he’d saved after retirement, I found a slug of folders arranged in alphabetical order. Each contained articles, memos or sample forms dealing with one subject or another, starting with “A”—“Assignments,” “Affidavits,” “Application Forms” (with alphabetically arranged sub-folders). The first folder among the “Bs” was “Bad Examples.” I laughed out loud, pulled out the folder and examined the contents. Dad was a stickler for both accurate form and proper substance. In the “Bad Examples” folder was a collection of court orders on which he had circled errors of form and substance.

I also found large caches of letters and copies of letters that our parents had written and received over the decades. They covered a broad range of civic and vocational activities and reflected lives that had contributed much to the community—the Red Cross, the Minneapolis Institute of Art, Junior Great Books, the Guthrie Theater, church governance, and a host of other enterprises, in which Mother or Dad or both were not just active participants but leaders who knew how to wield a pen and typewriter. The biggest treasure trove of writing, however, took the form of personal letters among members of our family—not “Hi, how are you doing; well, I hope, I’m doing fine” correspondence but deep discourse about a broad range of personal matters and artistic, religious, political, literary topics.

The richest find appeared in a bulky, colorful Boston Coffee Cake box. Late one evening I was hard at work in a corner of the basement, where Dad had been organizing various papers pulled from the attic. When I glanced at the time—11:30—I stepped back, surprised and a little disturbed by how immersed I had become. I had a full plate on my desk at work the next day and needed to get moving. But as I donned my jacket, I ran my eyes over the stack of boxes that I planned to tackle during my next session at the house. That’s when the red, blue and yellow Boston Coffee Cake box caught my attention.

I pulled it off the stack, placed it on a table and lifted off the cover. Inside were two rows of tightly packed, large, brown envelopes, each bearing a date, in chronological order. I pulled one out randomly and removed its contents—another, smaller, white envelope and folded sheets from a yellow notepad. In short order, I identified my discovery: 20 years of correspondence from my great-grandmother in Sweden to my grandmother, along with Dad’s meticulously and beautifully scripted translations. There in that box was a most elegantly presented record of family history, providing a fascinating insight into influences that shaped our family’s outlook and personality.

* * *

In time I worked my way into the den. During the course of Dad’s 25-year retirement, that room had become exclusively his domain. One wall was lined with bookshelves crammed with volumes. Against another wall was a sofa under a row of four, large, reproductions of Charles Remington cowboy paintings that Dad had purchased on our family road trip to Yellowstone in 1963. The frames he’d built in his workshop in the basement. The Remington cowboys faced the front windows which allowed a view of the street and beyond the opposing vacant lot, the Mississippi.

Planted against the wall facing the floor-to-ceiling bookshelves since the day we’d moved into the house was a tall, wide, maple secretary. Its shelves were filled with more books, including a multi-volume set of the entire works of Shakespeare. The secretary’s set of five lower drawers contained papers and mementoes that had not been disturbed for many years. Between the shelves and the drawers was a foldout desk, which had been open for as long as I could remember. For many years, Dad used the desk as workspace for paying bills and writing letters, but in time it became an uncharacteristically untidy repository for a large assortment of unorganized paper.

On that memorable day in June 2010, the unorganized paper was several inches deep. I started at the center top and worked my way to the edges, one piece of paper at a time. It was slow going. A Nutrition newsletter, an order form for special drill bits, a bunch of clippings from the op-ed page of The Wall Street Journal, a solicitation from “Warriors for Veterans,” an old utility bill stamped, “PAID,” a two-dollar bill, half-a-dozen issues of The Livingston Letter—a rightwing, doomsday publication—and a letter from a cousin in Sweden. I picked away, pitching each piece into one of three boxes. One I’d marked “RECYCLING,” another, “FINANCIAL STUFF,” and a third, “PAPERS SAVED FROM DEN.” A good half hour passed before bare wood was exposed.

Next came the drawers. For the contents of these, I used the same set of boxes but added a fourth, marked “OBJECTS FROM DEN,” so as to accommodate such “finds” as the slide rule Mother used while employed as a wartime aerospace engineer at the Curtiss-Wright plant in Caldwell, NJ. I approached the drawers in descending order.

By the third drawer, I had been at work on that secretary for the entire length of Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony, which I’d put on the living room CD player at a “pumped-up” volume. After the grand finale, the house fell silent again. I’d gotten to papers that hadn’t been touched since Jenny was in grade school; I could tell because that’s what I had come across—Jenny’s school papers and a couple of her elementary school report cards. Finally, I was encountering a semblance of organization regarding the contents of that secretary. The whole drawer, apparently, had been allocated to Jenny’s work.

I found amusement in her drawings from second grade, her stories from third grade, the plays she wrote the summer after fourth grade, a post-card she’d written as an 11-year old from Cass Lake Church Camp, and the note she’d stuck on the back door one day when, as an eight- or nine-year old, she’d been left home alone for a short while and had decided to bike down to the corner store about a half mile away. She locked the back door and taped a note to it to inform whoever might return home before her, where the key could be found. “The key is,” she wrote. But then she reconsidered. She scratched out her initial words and wrote below them, “The key is where it usually is.”

At the bottom of the contents of that third drawer, I found an envelope addressed to Dad. It yielded a letter, printed in pencil by Jenny’s hand. “Dear Lovingful Father,” it began. I couldn’t believe my eyes, as a flood of memories came back to me.

I grabbed my phone from my pocket and called Jenny. After a couple of rings, she answered.

“Hi, Eric. How’s it goin’?”

“Jenny . . . I found it!”

“Found what?” she asked, with puzzlement in her voice.

“I found your letter—your letter to Dad!”

“Huh? A letter? Which letter?”

“Jenny,” I said with the delight of a child, “the letter you wrote to Dad begging him to let you get a collie!”

“O-h-h! You’re kidding!”

“Let me read it to you . . .’”

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2023 by Eric Nilsson