NOVEMBER 13, 2023

NOT ACCORDING TO PLAN

ANOKA, MN – AUGUST 15, 1967 AFTER ABOUT 2:30 P.M. UNTIL ABOUT 5:15 P.M.

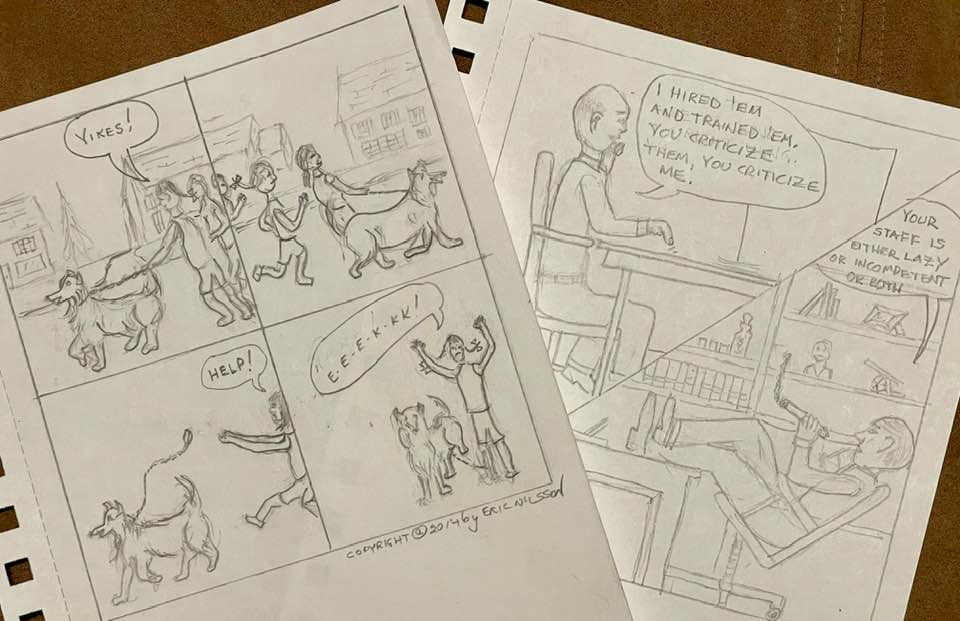

In retrospect, I have no idea why Mother thought she could leave a big, new, feisty, unruly dog unsupervised in the hands of three not-quite-nine-year-olds, but somehow she did. And I have no idea why the three not-quite-nine-year-olds thought they could walk that dog around the block, but somehow they did—or more accurately, the dog walked them around the block. I resumed catching grounders off the back wall of the garage.

The girls took turns taking the lead on the leash. Jenny was number one, Jane was number two and Beth was number three, as all three gripped the leash, bumped into each other and stumbled along as Björn panted and strained. After working their way around the block, they’d switch so Beth was number one and Jenny was number three, with Jane hanging in there as number two, and so on. I can’t remember whether they got tired out before I got bored fielding grounders or vice versa, but in time, Beth and Jane had had enough. They hopped on their bikes and were off. From that point forward until late that night, things got bad, then worse.

After scooping up my last grounder, I watched Björn lead Jenny, still gripping the leash with both hands, to the bowl of water that Mother had placed on the sidewalk just off the driveway. He slurped noisily for a few seconds, then licked his long chops as water and drool dripped onto the sidewalk. My eyes must have widened till my irises no longer touched my eyelids. Looking around, Björn resumed his rapid, continuous panting. I could see why Dad had not wanted a dog inside the house. But then the dog did the unspeakable. He lifted his furry leg and peed on Jenny’s bare leg.

“Ahhhhh!” The decibel level of her scream surely could’ve been heard from the backside of Moore’s house. It was certainly heard inside our house. But before Mother could reach the doorway, Jenny thrust her leash-clutching hands into my stomach and yelled, “Here! He’s yours!” Bolting straight for the house, she ran smack into Mother. Simultaneously, Mother’s inquiry—“What’s wrong?”—collided with Jenny’s answer—“He peed on me!”

If in fact I’d had any kind of purchase on the leash before Jenny let go, I lost it. In the commotion, Björn jerked free. However quick I thought I was at fielding unpredictable grounders, I was no match for a loose leash, flipping and flashing erratically like a diabolically crazed snake. Björn paid no mind to it. Like any dog bred for herding sheep, Björn tore around in a large circle with me in the middle. However much I tried to chase him, or more precisely, the leash that trailed him, he was able to shift his circle to keep me on the inside.

Eventually, I gave up and joined Mother and Jenny on the front steps. None of us had a clue as to what to do next. Panting as hard as ever, the dog assumed a playful stance on the sidewalk, then barked, as if to prod us into resuming the chase.

“He’s scary, Mommy,” said Jenny.

“He’s just a little boisterous, dear,” Mother said. But she couldn’t fool me. Mother still had no idea what to do. Her next words proved it. “Eric, why don’t you try to get him into his cage—I mean, kennel.” To this point, I had not pondered how in the world Dad was going to react to the fact that we now had on our hands the most rambunctious dog I’d ever seen. And what would Fred think of Björn’s barking? I could not visualize a happy ending.

Slowly—ever so slowly—I moved toward Björn, but after a step and a half, he’d spring and spread his forepaws on the sidewalk, positioning himself for take-off. It took several tries, but eventually I got close enough to step on the leash, then grab it with both hands. Wrapping the leash around one hand, and holding on with the other for dear life, I walked a wild zig-zagging route back to the kennel. Once inside, I closed the gate as fast as I could before unclipping the leash from Björn’s collar.

By this time, Mother had caught up with me. Jenny was nowhere to be seen. Mother was holding Björn’s water dish and passed it to me over the top of the fencing. While the dog slurped, I slipped out of the kennel and latched the door behind me.

For the rest of the afternoon, the beast was in his pen, but I worried what would become of him, of us, of the world, when Dad came home from work and discovered that what had started out as Jenny’s fantasy had turned into a big flop. To escape, I wanted to jump onto my bike and ride across town to where all of my friends lived. But at 4:30, I wouldn’t have time to get there, hang out and get back before supper. Besides, as much as I wanted not to be on hand for what was likely to be an unhappy situation, something inside me suggested that I owed some kind of duty to Jenny and Mother to buffer them from Dad’s almost certain displeasure.

Just as I was mulling this over while on my bike circling the driveway, I heard another outbreak of barking. By now I was attuned to variations in Björn’s bark. There was the friendly bark—the quick, sharp “Woof!” that sounded like a greeting, given at close quarters, followed by panting, then another “Woof!” Then there was the double-bark, followed by a brief, non-threatening growl, again, at close quarters, signaling that he wanted to play. Another kind of bark, heard from a distance, sounded plain even a little sad, accompanied by a short whine. I thought that signaled loneliness and a call for company. But what I heard just then, was agitated barking; barking that featured a falsetto, which, as time went on, I came to associate with the collie breed, for I didn’t hear it in other breeds.

I parked my bike and walked around the front corner of the house to see what was causing the commotion. What appeared was the big dog standing on his hind feet, his front paws resting two-thirds the way up the fencing of his kennel and his long snout pointing upward, jaws snapping forth the loudest bark I’d heard thus far. I had no doubt that it was fully audible inside Moore’s house across the street, even with their central air in full gear.

Twenty feet directly above the kennel, racing back and forth across the telephone wire was a fat and sassy squirrel. It was in squirrel heaven, driving the far bigger, earthbound animal to wild distraction. For all of his careful planning, Dad had overlooked a serious problem. How now in the world would we—would Dad and Fred Moore—have peace? My worries deepened.

I don’t know how Jenny spent the rest of the afternoon. Probably, she was in her bedroom with the door closed. I’m sure she wasn’t reading dog stories by Albert Payson Terhune.

* * *

As we would all soon discover, matters were not being helped by the fact that at work that day, Dad was facing challenges quite apart from an unruly collie. I don’t know the particulars, but from the stories Dad told over the years at supper, I imagine it involved one of two kinds of people: someone with a really bad idea or someone wanting to cut corners. Dad didn’t suffer fools, and he was intolerant of dishonesty, moral or intellectual. If I could guess, an encounter with dishonesty is what had put him in a foul mood by the time he pulled into the driveway.

Perhaps it had unfolded like this . . .

* * *

Seated at his office desk, Dad looked quite stressed out, pondering a document while rubbing slowly his bald pate with one hand and underlining words with the other. His desktop was covered with paper, but poking up was a solid brass nameplate that identified Dad by name and title: RAYMOND NILSSON/CLERK OF COURT. Fifty years later, that nameplate would grace my law office.

Alice Lindgren, Dad’s most senior and trusted deputy, approached the doorway and rapped her knuckles on the metal door-frame. “Knock-knock,” she said. Dad looked up. “Sorry, Ray. Bob Lindstrom of Olson and Johnson is on line three. Insists on talking to you. He wants a judgment entered before Judge Knutson signs the order. Everyone’s told him no. Can you take his call?”

Dad sighed. “That arrogant son of a gun? Okay.” He lifted the receiver from his desk phone and punched the flashing button below the rotary. “Ray Nilsson,” said Dad.

Meanwhile, at the other end of the line, with phone receiver in one hand, and a lit stogie in the other, Bob Lindstrom, a high-powered attorney in the First National Bank Building in downtown Minneapolis sat at his desk in his posh office.

“Bob Lindstrom at Olson and Johnson,” the lawyer said. “I don’t know what’s goin’ on in your office but your staff doesn’t follow directions very well.”

“Oh?” said Dad the same way he’d say “oh” to us at home whenever any of us said something that was suspect.

“No. At the hearing yesterday Judge Knutson clearly said he was granting my motion. Today I’ve asked three of your deputies to enter judgment in favor of my client, but none of them seems competent enough to do that. Or is it that they’re just too damn lazy?”

“First off,” said Dad, adjusting himself a little higher in his chair, “I resent your talking about my staff like that. I hired ’em and trained ’em. Criticize them, you criticize me.” If Dad didn’t suffer fools, he was fiercely loyal to the smart, competent people on whom he relied.

“Let’s cut to the chase here . . .” said the lawyer.

“No, you let me finish.” Dad cut him off. “In the second place, Judge Knutson hasn’t signed the order yet. I was in the courtroom for that hearing and what he said was he he’d sign an order revised to his specifications regarding the interest calculation and attorneys’ fees. Until he actually signs the resubmitted order you prepared, we can’t enter judgment, and you know that.”

The lawyer took to his feet and blew out a big puff of smoke. “Whoa, whoa, whoa!” he said. “Since when does your office take sides in a case?”

“We’re on the side of doing the right thing,” Dad said, fighting to keep his voice steady. “What side are you on?”

Dad could hear the lawyer drawing deep on the stogie and blowing smoke into the phone. “If I remember correctly,” Lindstrom said, “you’re up for re-election next year aren’t you?”

Dad jumped to his feet. “If that’s a threat,” he said, raising his voice, “this conversation is over.” Dad slammed down the receiver onto the phone cradle, tossed papers into his briefcase, slammed it shut and grabbed it, snatched his suit coat off the hangar on the wall, smacked off the light switch and stormed out of his office.

He approached the desk of Alice Lindgren, who wore a curious look. “I told him ‘no,’” he said to her.

* * *

Dad pulled into the driveway and braked uncharacteristically hard. He stepped out of the Electra, pulled his briefcase and suit coat out and slammed the car door. He took two steps from the car, stopped abruptly, went back, opened the door and tossed his briefcase back onto the front seat. Then, looking straight ahead, without so much as a cursory glance at the lawn, he marched to the front steps, snapped open the screen door and entered the house.

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2023 by Eric Nilsson