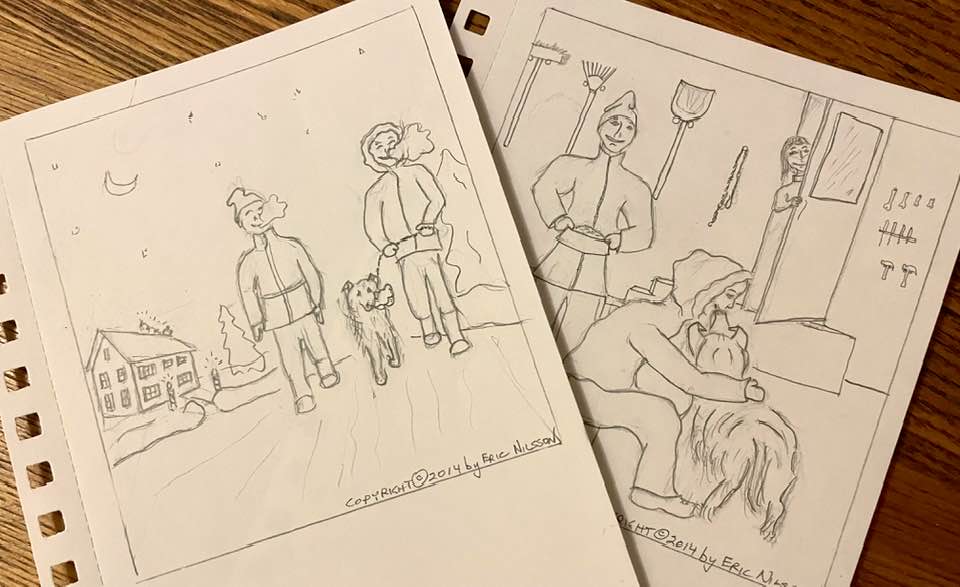

NOVEMBER 20, 2023

A MAN’S BEST FRIEND

ANOKA, MINNESOTA – DECEMBER 1968

We piled into the house to the sound of dueling three-octave scales and arpeggios emanating from the two violins upstairs. “We” were Mother, Dad with my suitcase, Jenny, and I in my white shirt, tie and Sterling blazer showing through my open overcoat. The glass in the storm door fogged up instantly when the warm air inside the house condensed upon the glazing. “Quick,” said Dad. “Let’s not heat the whole outdoors.” As he shut the door, I turned and saw that the Christmas tree, fully decorated, was already in its place in the front of the living room off to the left of the entrance.

“Woo-hoo, girls!” Mother called up the staircase. “Eric’s home!” An octave or so later the violin-playing stopped, and Elsa and Kristina soon appeared to welcome me home. Kristina had arrived back from college and Elsa from her boarding school a day or two ahead of me, and had opted out of the family airport welcoming committee in order to log some extra practice time.

“Gee,” Elsa greeted me. “You look like a grown-up.”

I took that as a compliment, but in a moment of doubt, I said, “Hi,” as Kristina added her reaction.

“. . . Yikes!” she said. “You look sharp all of a sudden! Do your grades match your new look?”

I deflected her question with “Sure.” In fact, I had turned many corners in a short time. My grades were all that Dad could have wished for. We completed our greetings as he plugged in the Christmas tree lights. “Isn’t that a nice tree, Eric?” He said, admiringly.

“Yes, it is,” I said, but I was more eager to see Björn. To my surprise, Dad pre-empted me.

“Well, now,” he said. “Why don’t we change into walking clothes and take Björn for a walk before it gets any colder out there.”

* * *

A deep blanket of snow covered the backyard and sparkled in the beam of the new floodlight off the back of the house. I followed Dad from the back steps of the garage and down along the trench that led to the kennel. With his insulated boots, he had beaten a daily path a foot below the surface. He was dressed for 20 below, and in Dad’s gait I saw his embrace of winter. He was out in the cold not because he had to be but because he wanted to be. As we approached the kennel, Björn emerged from his warm, cozy house to greet us. His tail wagged enthusiastically, and as his warm breath met the frigid air, a thin cloud formed around his regal face.

“Hej, hej!” Dad greeted Björn. With his over-sized chopper mittens, Dad ruffled the happy canine behind the ears. When I dropped to my knees, Björn turned to me. I gave him the biggest, longest hug I could manage.

“Björn!” I said, my cheek pressed against his fur. “How I missed you! Did you miss me?” As if on queue, he answered with a light bark.

“Of course you missed, Eric, didn’t you, Björn?” Dad said. The dog then turned his attention back to Dad, who leaned down and patted him on the side. “You want to go for a walk?!” said Dad, looking Björn right in the eyes. Björn answered with a definite ‘yes!’ As Dad pulled Björn’s food dish and water dish from the doghouse, Björn exited the kennel and made his way up the trench through the snow to the back steps of the garage. Clearly Dad had established a routine.

Inside the garage, Dad handed the dog dishes to me. “Give these to your mother so she can get Björn’s dinner and trade that chunk of ice for some water.” I peered into the water dish to see that ice had formed. As instructed, I stepped inside the house, where Mother was waiting.

When I returned to the garage, I saw Dad down on one knee, cradling Björn’s head and looking into his eyes. “Du är en finn hund, Björn,” he said in Swedish— You are a fine dog, Björn. “Och vi är en vackert par, ja?” – And we are a beautiful pair, yes? Dad laughed at his own words. “Ja, ja! Du är vackert, men vi är en par!” — Yes, yes! You are beautiful, but we are a pair!

“You talk to Björn in Swedish?”

“Why not?” Dad said, smiling “He’s a smart dog . . . just like his master.” Dad laughed. “Ska vi gå?”—Shall we go? It took me a moment for the words, “like his master” to sink in.

Björn barked once, lightly, and wagged his tail. Dad lifted Björn’s leash from the can opener that Dad had installed on the back wall of the garage, next to the back door, for cutting out the bottoms of empty tin cans so he could flatten them before tossing them into the garbage can. He clipped the leash to Björn’s collar, and handing the light chain off to me said, “Wanna do the honors?” I gladly accepted and allowed Björn to lead us out of the garage.

Our footsteps crunched along the hard-packed snow on the street. By that sound you could tell the mercury had slid below zero Fahrenheit. Nothing else in the still night moved. “I’ve really missed Björn,” I said.

“Small price for turning your life around,” said Dad.

“I guess so,” I allowed.

“Besides, it sounds like you’re actually learning something there at that school,” said Dad, pulling a handkerchief from the pocket of his parka to dry his eyes, watering in the cold.

For all its faults, the school had turned my life around. I had responded successfully to the academic rigor to which my schoolmates and I were held to account. If my weekly calls home had been brief and superficial, my letters home had been long and substantive. We were a family of writers, and being away at school had encouraged the habit among my sisters and me.

“Yeah,” I mean, we have to think hard about stuff, and I kinda like that.”

“Thinking hard about things is a good thing. Problem with this country right now is that half the people don’t think about things hard enough. Just look at how many people voted for Humphrey—Nixon won by only a whisker. If Humphrey had won, we’d be surrendering in Vietnam, and the Russians would think they could just run roughshod over the rest of the world, and . . .”

I began to ignore Dad’s harangue. It was certainly at odds with what many of my peers and teachers back at Sterling believed, but I wasn’t about to get into that with Dad—not yet, anyway. Björn, meanwhile, kept his nose pointed in the cold, dense, night air, as he trotted along at my side. He heeled so well, the leash stayed entirely slack. If I Dad’s politics clashed with the views to which I’d been exposed at Sterling—views I was beginning to adopt as my own—I couldn’t complain about how Dad had cared for Björn during my absence.

* * *

He knew a lot of people, and a lot of people knew him—or at least they knew his name: his office issued driver’s licenses, and in keeping with a decades-old tradition, everyone who got a license got a nice little, dark red, stiff-paper holder to go with it. On the front of the holder Dad’s name and title were prominently displayed:

RAYMOND NILSSON

_____________________________

Clerk of District Court

Back when the office was elective, the holder did double duty as a campaign sign in every driver’s pocket. Why wouldn’t you vote for the guy who gave you your license to drive around town and beyond?

The local prominence of Dad’s name didn’t translate to a circle of close friends. Dad wasn’t a joiner, a drinker, a golfer, a sports fan or a back-slapper. Except for Fred Moore and people at the courthouse, Dad relied almost entirely on Mother for social connections, and he participated on his own time and terms. He was cordial enough within Mother’s network, but if he couldn’t enjoy a detailed, one-on-one conversation about a subject or matter that interested him, he preferred to be left to his own devices.

As the seasons came and went, Dad applied to Björn’s care, Dad’s characteristic discipline and attention to detail. What had begun as a task had developed into an abiding affinity for the dog. In time Björn had become the man’s best friend.

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2023 by Eric Nilsson