NOVEMBER 4, 2023 – (Cont.) I turned off the paved county road and onto Coppersmith Road, a narrower dirt road serving Björnholm and two neighboring cabins to the east. As was my custom at the juncture, I switched off the A/C and lowered the windows to fill my lungs with fresh, northwoods air. So Beth wouldn’t complain about what the wind would do to her hair, I slowed way down, which had the added benefit of letting me savor the view of the woods that crowded the earth right down to the sides of the road. I thought of the trees as a huge welcoming party, cheering our return for the weekend from a week of frenetic urban life. Our boys, Cory – 12, and Byron – 9, noticing the change in air, put down their Game Boys and picked up their Nerf guns.

Out of necessity I slowed even further when we reached the beginning of our long drive leading from Coppersmith Road back to the cabin. The drive is barely the width of a mid-sized car and consists of two tire lanes separated by a grassy hump. We moved up the long, gradual slope from Coppersmith Road, then meandered along the drive past the stands of big pine, finally reaching the base of the steep hill behind the cabin. That’s where you have to gun it, and by so doing, you announce your approach.

As our car reached the crest and pulled into the yard just short of the wood piles, I saw Dad swing his maul down on big piece of oak. At 75, he had the strength of a much younger man. The oak split cleanly, each half falling back upon itself.

* * *

After unloading a few things from the car and changing into our swimwear, Beth, the boys and I headed out the front door of the cabin. The screen door slammed in synch with Dad’s splitting maul smacking another oak log. Though he was lord of the manor with a quarter mile of lakeshore, Dad was not a water person. Once in a great while I could get him out in the old, Alumacraft rowboat, but the draw was always the view of the trees along the shore and from a distance of not more than 200 feet. For Dad, other than those purposeful excursions, usually after supper and a day full of projects, the lake was merely a scenic feature of his surroundings and not a place for recreation. Dad didn’t have much use for recreation, water-based or otherwise. He left swimming, boating, canoeing, sailing, fishing, sun-bathing, hanging out on the dock to the rest of us.

With our towels slung over our backs, Beth and I headed across the west yard toward the top of the earthen steps that lead down the wooded hill toward the dock. Cory and Byron tore around us, using Beth and me for cover while shooting their Nerf guns at each other. After a few paces, I stopped by the cairn where the yard yielded to the wild, pine-guarded slope that drops precipitously down to the lake. Through the trees I eyed the sparkling lake below. Of all the vantage points along our shoreline, the view from that spot was my favorite. It was Dad’s favorite too. That’s why he’d chosen the spot for . . . the remains.

Back on the path but now well behind Beth and the boys, I descended the earthen steps to the wooden staircase leading down to the dock. The Nerf guns lay on the ground at the top of the stairs. With my foot, I shoved them aside and leaned on one of the posts that supported the staircase—just as solid that day as it had been 44 years ago, when as a four-year old, I’d watched Dad install it. The big Norway that leaned over the steps was much larger now and its limbs offered a good bit of shade from the August sun.

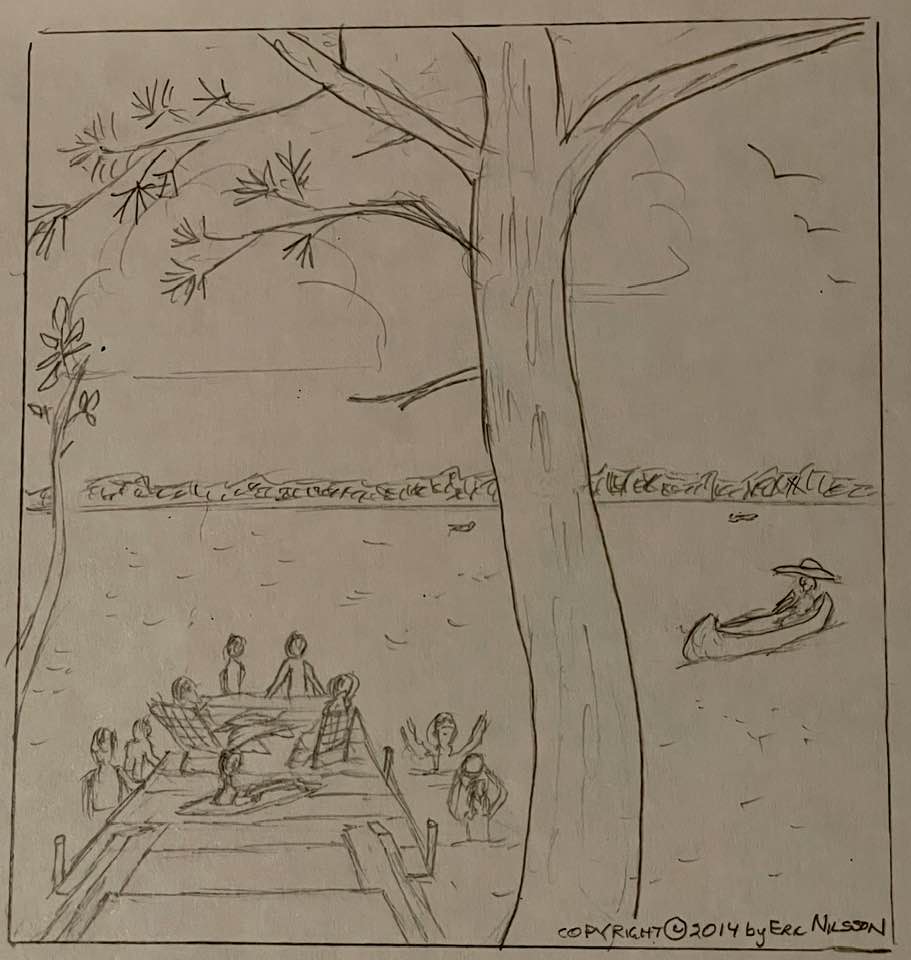

For a few moments I stood there, not yet noticed by my sisters, who were sunning themselves on the dock below or by my brothers-in-law and nieces who were swimming and carrying on in the water—or by Mother, in her gigantic straw sunhat, paddling her small, aluminum canoe in a big, lazy circle within an easy rescue distance from the dock. I contemplated how pleased my grandparents would have been to see three generations of their descendants enjoying the place that Dad, their only child, had inherited and preserved so well. After a minute or two, I moved down the steps.

Kristina was the first to see me. “Happy Birthday, Eric!” she cried out.

“Thanks,” I said. Mother, I noticed, was making her way back to port. She saw me too and began singing “Happy Birthday.” Within a note or two, every mouth that was above water joined in. Before more than a bar or two, the harmonizers among the group found their parts.

After greeting everyone, I turned to Jenny, whose stomach looked quite a bit bigger from when I’d last seen her. “Are you sure that baby hasn’t turned into a beach ball?” I asked her.

“Well, it doesn’t float like one!” she said.

“Is Garrison on his way?” I asked.

“Yeah, he flew back today. Linda and David were picking him up at the airport and taking him to their parents’ house for a little cake ‘n ice cream.” The mention of Linda and David made me smile. I so enjoyed Garrison’s smart, warm, funny, younger sister and her endearingly curious and quirky husband. “Then he’s coming up.“ Jenny said. “He should be on the road soon.”

“In time for more cake ‘n ice cream?” I said.

“If he doesn’t get lost.”

We laughed. As my younger sister, Jenny was the one I’d picked on when we were kids. Our two older sisters were high achievers out of the gate, and at any given time, I was either in awe of or intimidated by them. Not so with Jenny. Always at least a head taller and three years older, I could lord over her and often did. The advantage of seniority was diminished, however, when Jenny, already a voracious reader at age six, was allowed to skip first grade. But eventually I grew out of my self-appointed role as Jenny’s boss, and in time we’d become the best of friends.

* * *

Jenny’s famous radio-personality husband shared my birthday, but he had more than that in common with us Nilssons. He was born in the same house as Jenny—an old, Victorian, four blocks from our home in Anoka, Minnesota, that had been converted into a hospital and marked outside by a blue, neon “Hospital” sign atop a black pole. Garrison—whose real name was just plain “Gary,” though the only two people I ever heard call him that were Linda and David—graduated from Anoka High School and was well-acquainted with many of the people our family knew. In fact, it turned out that he was related to many of the people we knew well. Nearly every summer, he took his signature radio show, A Prairie Home Companion, on national tour, but that year, he happened to wind it up just early enough to make it home in time for his birthday.

Garrison had only been to Björnholm once before. It was in the fall, on a weekend when a rerun of the show instead of a live one was being broadcast on national public radio. Somehow Jenny had coaxed him to endure an over-night at the cabin with her, Mother and Dad. Around mid-morning Saturday, Beth, the boys and I hiked over from our own family cabin, which was tucked away on a secluded lot adjoining the far end of Björnholm. When we reached the old family cabin, we weren’t the least bit surprised to see Dad on the roof, inching carefully but confidently along the edge, scooping and tossing debris from the gutter. But seeing Garrison do a nervous crab walk higher up on the roof was a complete but amusing shock.

I didn’t dare ask what in the world my big, tall brother-in-law was doing up there, but I imagined that after a hearty breakfast, Dad had announced that he, Dad, was going outside to attend to his fall maintenance task of clearing out the gutters. Garrison, no doubt, had wanted desperately to retreat to a quiet corner of the cabin to write but perfunctorily volunteered to help, expecting that Dad, who always worked alone, would not want help and therefore wouldn’t accept it. But not wanting to offend Garrison, Dad had probably said reluctantly, “Sure!” and assigned him the adjunct and limited task of clearing the roof of small branches that strong winds had trimmed off the trees that arched over the cabin. It was a safer job than clearing the gutters, since Garrison could stay well away from the edges—once he’d gotten himself up the ladder and onto the roof in the first place.

Dad greeted us confidently. Garrison managed a nervous greeting—barely. I laughed silently at the thought that he was too nervous to see himself as the subject of one his own classic radio monologues that had given him so much fame and fortune.

* * *

We all enjoyed another hour or so of sun, water, water toys, banter and conversation—and simple revelry around a small place in the world that was our place. As the breeze dropped and the sun slid to an angle that reflected more sharply off the water and into our eyes, Mother and her canoe found their way closer to the dock.

“I suppose we should start thinking about supper,” she said. With that pronouncement, the protracted exodus began. First the women, ever the leaders of my generation, then two out of my three brothers-in-law, then the older cousins, then my sons, whose energy in and out of the water never waned. I picked up the rear—and a snorkeling mask, a kid’s flip-flop and a paperback that had been left behind.

Not the Nerf guns, however. The boys had picked them up and were engaged in open battle higher up on the hill. I hiked up the earthen steps, and upon reaching the combat zone, gave the obligatory parental command.

“Come on, guys. We gotta get ready for dinner,” I said, knowing full well that Beth had already given the order and that I would be directed to repeat it soon after I reached the cabin. I kept walking.

The boys stormed through the ferns, stomped on the wintergreen, the wild blueberry plants and the trillium that covered the ground beneath the trees. Each of the two kids hid behind one trunk or another, then sprang forth to ambush his brother and launch a Nerf missile, another and another. After each salvo, they’d dash around to collect their renewable rounds, load up and repeat the order of combat.

Just before I was directed to call again the boys into the cabin, one of Byron’s Nerf projectiles went missing. Together the brothers searched the grounds. The yellow, tubular piece of Styrofoam had landed atop the lichen-covered cairn. Eventually, Byron spotted it.

“Cory, I found it!” he cried.

“Hey, guys! Time to come in!” I shouted from the front steps of the cabin 50 feet away.

“Yeah, we hear ya,” Cory shouted back. Three calls were the charm with two generally obedient boys. I stepped back into the cabin. He walked up to his brother as Byron pulled a stone off the cairn, examined it for a moment, then returned it to the pile.

“What is this for?” Byron asked, taking a step back and gazing at the cairn.

“I dunno,” said Cory. “Grandpa must’ve put it here.” He turned to make his way to the cabin. “Come on, Byron,” he called over his shoulder.

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2023 by Eric Nilsson