NOVEMBER 17, 2023

A “BEAR” IN THE WOODS . . . AND INSIDE THE CABIN

GRINDSTONE LAKE, NW WISCONSIN – SEPTEMBER 9 – 10, 1967

The evening before, Dad had announced his intent to head up to the cabin first thing Saturday morning to check on Grandpa, who was still summering up there alone, and summer wasn’t quite over yet. And then there was the annual fall ritual of hauling out the dock, the old boat lift and the Alumacraft. Mother had no desire to go up, and Jenny wanted to stay behind with her, so only Dad and I would be going. The week before, Kristina had flown off for her freshman year of college out East, and Elsa had left for her sophomore year of high school at a boarding school in Michigan for the fine arts.

On trips to the cabin, Dad always carted various tools and supplies, usually in boxes of various sizes, arranged in the trunk so as to minimize wasted space—wasting anything was sacrilege to him. By the time Dad was maneuvering the last items into position to make room for my violin case, I summoned the gumption to ask what had been on my mind since the night before. “Dad,” I asked, “can we take Björn to the cabin?”

“No, I’m afraid not,” he said, taking the case from my grasp and fitting it securely between a box marked, “WORK GLOVES” and one with the lettering, “CLEAN RAGS.”

“Why not?” I asked, feeling more confident, now that I had asked the initial question, despite Dad’s negative response.

“I don’t want dog hair and slobber all over the inside of the car.”

“We could spread out rags or somethin’,” I said.

“But then where are we going to put him once we get there?” said Dad, as he pressed his weekender suitcase into the dwindling available space in the trunk. “I don’t want him getting mixed up with a skunk or a porcupine.” Dad grabbed the last item to go in—a small duffle bag.

“We can’t leave him outside at night and we can’t have him inside.”

“We could put him on the back porch, couldn’t we?” I said. “And don’t you think Grandpa would like to see him?”

Dad shoved the duffle bag into place. “Well . . .” he said, closing the trunk lid. “. . . Okay. Ask your mother for some old towels to cover the back seat with. And we’ll need his food dish and some food.”

I recalled silently the night when Dad had turned the hose on Björn. Maybe now I could overlook the cruelty he’d exhibited then.

* * *

As Dad finished laying out the towels across the back seat of the Electra, I stood on the other side of the car and coaxed Björn in. Dad was right. Björn did slobber—a lot—and what I saw that Dad couldn’t see is that most of the dog drool wasn’t landing on the towels covering the seat and back floor. It wound up on the back window on the driver’s side and down the interior side of the back door.

Three hours later, after an otherwise uneventful drive, we pulled into the yard at the cabin. Grandpa was splitting firewood—not at the dexterous speed with which Dad approached that subject, but for an old guy of 76, I thought, Grandpa did pretty well. And, I figured, if he weren’t smoking one of his Ri-O-Tans, he wouldn’t have to take time to flick the ashes. On the other hand, if he quit smoking, he wouldn’t have more cigar boxes for storing recycled bolts, nuts and washers in the garage.

Before Dad had time to switch off the ignition, I sprang out of the car, and opened the back door to hook the leash to Björn’s collar. He needed no incentive to get himself out of the back seat. I walked him around the car to show him off to Grandpa.

“You brought Björn!” Grandpa said with a hint of uncharacteristic delight. With tail wagging with its usual enthusiasm, Björn nuzzled Grandpa’s outstretched hand. “Dad said we could bring him,” I said, not quite believing myself but needing justification. If Dad was persnickety, Grandpa could be stern and disapproving. He had not shown much of a smile since our grandmother had died early the year before.

“Why don’t you let him run free?” Grandpa said.

“What?” I said. I’d heard him perfectly well. When Grandpa repeated himself, I unhooked Björn’s leash. The old man removed the working glove from his right hand and patted the happy visitor. Leaning over stiffly, the old man picked up a stick and tossed it toward the edge of the yard. With a mighty launch, Björn tore after it, snatched it up and carried it back to Grandpa.

“I’m glad you brought Björn,” he said. “Been lonely up here. Could’ve used a good friend like him around.” Grandpa threw the stick again . . . and again, and I got to see how a man and a dog become friends. Dad, meanwhile, got right down to the business of unloading the car.

If a hint of fall was in the leaves, the weather was still warm and on the humid side. Four or five throws into the pick-up game of fetch, Björn’s tongue hung farther down from his jaws. With his trademark walk—shoulders hunched, arms hanging down, bent slightly back at the elbows, Grandpa made his way from the woodpile to the water pump platform a few feet away from the east side of the cabin. He turned up the metal pail that was a fixture under the spigot. The well was deep—80 feet, Dad was fond of reminding us—which yielded the coldest, freshest, most delicious drinking water any of us had ever tasted. And now, I realized, Björn himself was about to get his first taste of it.

“Here you go, Björn!” said Grandpa, with a cheerfulness I hadn’t heard in a very long time. “You gotta be thirsty after all that runnin’ around.”

Björn knew exactly what to do. He stuck his snout into the pail and slurped away as if the water were some kind of addictive canine elixir. After an impressive intake, with water and drool dripping down onto the platform, Björn looked up at Grandpa with what looked to me like an expression of appreciation, then resumed slurping noisily. Grandpa leaned over and patted Björn on the side. “Good dog,” he said. “Good dog.”

In time, Dad reappeared in his work clothes and headed down to the garage to dive into whatever project he’d put on hold ever so reluctantly upon the end of his latest prior weekend at the cabin. Grandpa relit his cigar and resumed splitting firewood. With Björn on my heels, then ahead of me, I ran down the earthen steps on the west side of the cabin and down to the dock.

“Whadda ya think, Björn?” I said, rubbing my hand on the top of his head and looking out at the big liquid jewel. “Great isn’t it?” As if on cue, Björn barked lightly.

I turned and ascended the wooden staircase from the dock back up the bank. “Let’s go, Björn! I’ll show you more.”

I ran with Björn down the old Indian path through our woods along the lakeshore all the way to the end of our property, about a quarter mile to the west. With Björn dashing this way and that, sniffing here, marking his newfound territory there, I cut back into the woods and along the inner path that Dad had blazed for hauling out firewood. I’d seen no other creature—certainly no person—exude such delight in those woods as Björn displayed. His sable coat flashed among the trees and shrubs, as he charged around in giant circles around me.

Björn’s inaugural romp would be a minor precursor to his marathon expeditions in later years. He’d disappear for hours, then return, exhausted, panting, tongue hanging out, and large burrs riding on his long, collie coat. The burrs gave us some idea of how far he must have roamed—Dad had walked every square foot of our acreage, and he said he’d never encountered such burrs. However far Björn wandered, he was smart enough—or lucky enough—never to tangle with a skunk, a porcupine or some form of wildlife that was more of a danger than a nuisance.

We ended our expedition back in the yard where Grandpa was chopping wood. With the reminder of Grandpa’s cigar, we watched Björn walk to the water pail for another restorative swig of that delicious water. Just then Dad came up from the garage, carrying a couple of long boards having to do with his current project. “Dad!” I called out. “Björn loves it up here!”

“I can see that,” Dad said. His tone gave me reassurance. “This really is where he belongs.” Dad stopped and gave the broader scene his gaze. “Where we all belong,” he said.

Grandpa drew what looked like one of the last takes on the diminishing cigar. He let out a puff of smoke and said, “You betcha, Che-che,” the nickname he used for Dad when both men were in a good mood. Grandpa then looked at me and said, “Does the Crown Prince know why Björn likes it up here?” Without waiting for an answer, he explained. “Because in Swedish, his name means bear.”

“Speaking of bears,” said Dad, “I think Björn should spend the night inside on the porch so he won’t get tangled up with any real ones or other wild animals.”

Grandpa nodded in agreement, and thus began the long tradition of “a bear” occupying the inside of the old family cabin.

* * *

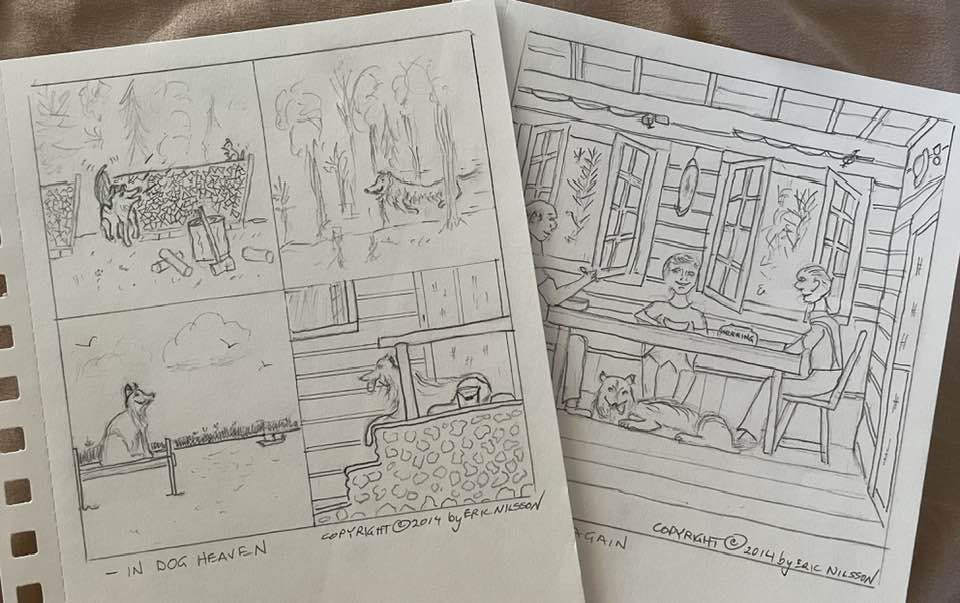

The next day brought more sunshine and warm air. By the time Björn and I had returned to the cabin from a long expedition, kitchen clock was just past noon. Lunch was already spread out over the table on the back porch. Back in the day, my grandmother was solely in charge of the kitchen and all meal preparation, but as it turned out, Grandpa and Dad were perfectly capable of laying out the sill—the herring—and knäckebröd, heating up a can of soup and making ham sandwiches with lettuce and mayonnaise.

Dad and Grandpa were just taking their seats when Björn and I appeared at the back steps. I could hear the old RCA Victor cabinet radio playing from the living room. As Björn lay down at the top of the steps, dangling his crossed forepaws over the edge of the top step, I took my seat on the bench between Dad and Grandpa.

Back in those days, the radio picked up three stations—WHMS, the local radio station broadcasting from just outside of Hayward, WCCO, the CBS affiliate in Minneapolis, using a powerful signal, and in the late evenings, a rock ‘n roll station from Little Rock, Arkansas. Just before lunch, Grandpa had turned the dial to 8-3-0, WCCO, and at right at noon, we heard Lowell Thomas announcing the top of the hour news. He led with news about the war in Vietnam.

“We’ve got to improve our efforts over there,” said Dad, laying expertly two slices of sill on a piece of knäckebröd. “Johnson’s not doing enough . . . Ya can’t fight a war halfway.” When it came to politics, Dad had a way of making himself angry without the help of anyone brave enough to disagree with him. I sensed that with that jab at the President, he was working himself up to something. “It’s all or nothing. What we need right now is a Winston Churchill, a Douglas MacArthur and another 100,000 troops.” With that, he finally took a bite of the knäckebröd, catching one whole piece of sill in the bargain. After four chews and a hard swallow, Dad lit into the Democrats in Congress. “And those Democrats in the House and Senate don’t know any better either.”

Grandpa said nothing. He interrupted work on the King Oscar sardine can, and leveraging himself out of his chair, got up, walked into the cabin and shut off the radio. When he re-entered the porch, the look of disapproval weighed down his facial features. With a gnarly hand, he repositioned his chair and lowered himself onto it. I detected something between anger and annoyance in his movements.

“Ya know what war is?” he said, finally. He was scowling at me, but his words seemed directed at Dad.

“Huh?” I said.

“War is grown men cryin’ out for their mamas.” Grandpa, I knew, had been a in World War I, a soldier with an ammunition company, transporting ammo forward from behind the lines. He had seen stuff, he once told me, that no one should have to see. Dad, I knew, had avoided World War II. Hay fever—so bad it had exempted him from the draft.[1]

“I sure hope the war in Vietnam is over before I turn 18,” I said, in feeble acknowledgment of Grandpa’s somber and dramatic comment.

“That’s why I keep tellin’ ya, fella,” Dad said, “you’ve got to do better in school, get better grades, practice your violin, so if you’re in danger of getting drafted, you won’t wind up on the battlefield. Leave that to the C students . . . Dad,” he broke off. “Can ya pass me the sardine can so I can finish opening it?”

Grandpa complied by using his fist to slide the half-opened can toward Dad. “If ya’d put as much effort into your studies and into practicing your violin that you put into baseball cards and playing with the dog, you’d amount to somethin’ . . .” I didn’t like where Dad was headed. “. . . If ya amount to somethin’ and you find yourself in the army, you’re much more apt to have a safe job at a desk somewhere.”

“The violin saved my life over in France,” Grandpa joined in. Now it was both of them against me. “I knew a lot of soldiers who went where the fighting was and never came back. Me? Because I played the violin, the captain held me back. I got invited to play where the brass stayed, away from the front.”

“After lunch I wanna hear some practicing,” said Dad. There it was. I knew it. I knew sooner or later the P-word would come up. I knew that with those two, no escape was possible. After all, Grandpa was the one who had started each of my sisters and me on the violin. And if Grandpa scowled disapprovingly whenever he heard that I wasn’t practicing as I was expected to practice, Dad got downright verbally angry when he learned after work that I had whiled a whole summer day away without having touched my violin.

“Can’t I practice after supper instead?” I said, knowing full well the odds were against me.

“No,” answered Dad.

“Why not?”

“Because I wanna hear it after lunch, that’s why.”

Enough was enough. I didn’t believe for a moment that the violin would save me from Vietnam, and if Dad was so mad at President Johnson and the Democrats in Congress for not cranking up the war against the Communists, then why was he pushing me to practice so that I could avoid the draft? I stuffed the rest of my ham sandwich into my mouth and picked up my unused fork solely so I could drop it noisily on my plate. After chugging a swig from my water glass, I slid myself down the bench to get up from the table.

“Where d’ya think you’re going?” said Dad.

“To practice.”

“You didn’t ask to be excused.”

“May I be excused?” I said in a huff.

“Yes.”

With that, I stormed off into the cabin proper. Contemptuously, I grabbed my violin case, which, the day before, Dad had deposited carefully beside the piano. Stomping my feet loudly enough to be heard out on the porch, I entered the front bedroom and slammed the door. I was careful enough, however, not to slam it hard enough to make Dad to lose his temper.

For the next half hour, while Björn waited for me patiently from his throne of stone and mortar steps, Dad and Grandpa took care of the dishes. The old men got to hear me tear through the first movement of J. S. Bach’s Violin Concerto in A minor about 10 times, as loud and angrily as I could make it. Serves them right, I thought. And good thing it’s in a minor key, too.

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2023 by Eric Nilsson

[1] As an alternative to military service, Dad shipped off for Miami for a few months, where he translated instructions to a Swedish machine gun that the U.S. Army had ordered from neutral Sweden. The only story that his experience generated—retold many times—was the trouble-ridden Greyhound bus that had had to ride from Miami to Jacksonville on his return trip.