NOVEMBER 7, 2023

PERSUASIVE WRITING – ANOKA, MINNESOTA – JULY 7, 1967

Undaunted by Dad’s unequivocal kibosh of her idea of getting a dog, not-quite-nine-year old Jenny resorted to honey. That is, she sat down and wrote him a letter. Spreading honey in that fashion came naturally to her.

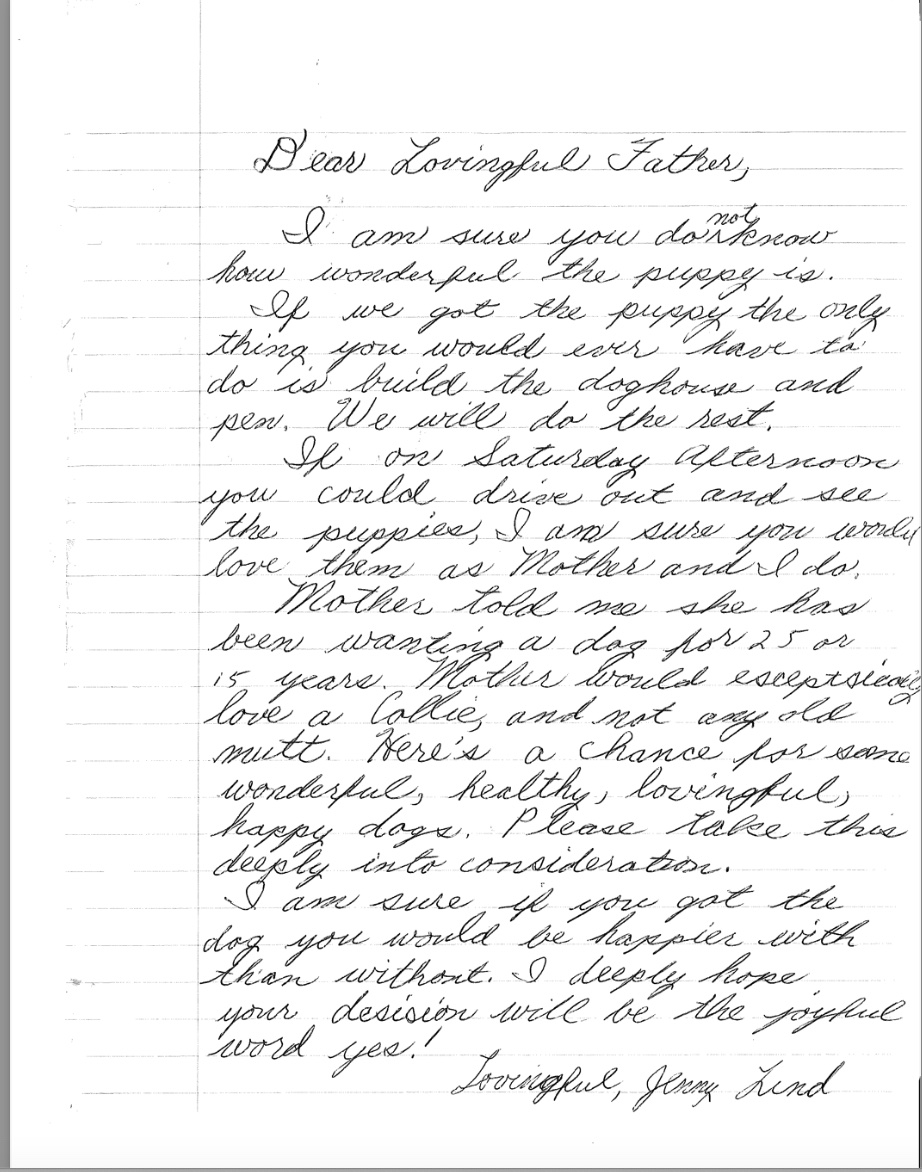

Dear Lovingful Father,

I am sure you do not know how wonderful the puppy is. If we got the puppy, the only thing you would ever have to do is build the doghouse and pen. We will do the rest. If on Saturday afternoon you could drive out and see the puppy I am sure you would love him as Mother and I do. Mother told me she has been wanting a dog for 25 or 15 years. Mother would esceptialy [sic] like a collie and not any old mutt. Here’s a chance for some wonderful, healthy, happy dog. Please take this deeply into consideration.

I am sure if you got the dog you would be happier than without. I deeply hope your decision will be the joyful word yes!

Lovingful, Jenny Lind

Ignoring the non-honey “ERIC NOT ALLOWED” sign on her bedroom door, I entered the room just as she was finishing the letter. She turned around and exhorted me to leave. Curious about what she was up to, I grabbed the sheet of paper and began reading it to myself.

“Give it back!” she cried.

“I’m gonna read it first,” I said. She snatched it away, but I didn’t have any interest in reading more. I had all I needed to harass.

* * *

Ironically, it was Dad who had planted the idea of getting a dog. For Christmas in 1964, Dad had given me an old book called, The Heart of a Dog, a collection of dog stories by Albert Payson Terhune. He said he’d read it when he was my age—10—and that it was an “excellent” story. Dad explained that Mr. Terhune had lived in a rural part of New Jersey and had raised collies in the first couple of decades of the 20th century. On the cover of the big, blue hardcover book was a fine, color illustration of “Lad,” the hero-collie of one of the stories.

Dad’s pick was a good one. It was an “excellent” book, and I devoured it. I even went on to read Bruce, another book by Albert Payson Terhune, which also featured a collie, one that had been volunteered to work as a messenger dog on the front lines of the American sector along the Western Front in World War I. Jenny, meanwhile, plunged into The Heart of a Dog, and being a voracious reader, she read all 249 pages within a few short days.

But a huge chasm separated well-crafted books about dogs and dogs in real life. Dad expressed appreciation for the former but exhibited utter disdain for the latter. Whenever he caught sight of a dog on the loose in our yard, he’d give his own face an almost snarling canine look and yell, “Git!” More than once I saw Dad grab one of my baseball bats for good measure.

And perish the people who allowed their dogs to bark at night. This meant the Caines, who lived in a cluttered, modern, flat-roof house on the large river lot directly across from our old house and owned an adjoining, vacant lot directly across from our new house. Caines owned a couple of Labradors, which, when they weren’t on the prowl around the neighborhood by day were locked up in a kennel by night. Often some nocturnal critter would doubtless amble by the temporarily imprisoned dogs and send the canines into a barking frenzy. It drove Dad crazy.

Dad was in supportive company, however, with Fred Moore, who lived in the beautiful home on the sprawling river lot across the street and next to Caines’ empty lot. Fred and his wife, Ruth, were close friends of Mother and Dad. One of their kids, Sarah, was a friend and classmate of my sister Elsa. Fred and Ruth and my parents shared many interests, particularly classical music and conservative politics. Fred owned a business down in the cities, and though he constantly complained about encroaching government regulations, he must have been doing well for himself, judging by the size and elegance of the Moores’ house, the late-model Cadillac that Fred drove, the sporty convertible that Ruth waved from, the size of the Steinway in their living room, and the regularity with which a furniture delivery truck pulled up in front of their home to replace what were already nicer furnishings than we would ever have.

Dad and Fred were close buddies. When the weather was nice after work, they’d chat out in the yard—Moores’ or ours—and often Fred and Ruth would invite Mother and Dad over to visit after supper. Jenny and I would tag along, especially on hot and humid summer days, since the Moores were among the few people around who had central air. Ruth was always friendly and generous with cookies and lemonade, elegantly served. Fred was downright fun and funny. He liked to make wisecracks to humor Jenny and me, and he and Dad would engage in witty conversation.

Both men were archconservatives, and I remember well the two GOLDWATER/MILLER signs that Fred posted in his yard during the fall of 1964. Dad was envious. He too wanted to show his support for Goldwater, but because Dad was an elected official occupying a non-partisan position, he followed a strict, self-imposed policy of not voicing publicly any personal political views.

Although the Moores owned two benign house dogs, an aged Corgi named “Bambi” and a Chihuaua named “Chico,” Fred’s dislike of the neighborhood dogs matched Dad’s disdain. Apart from politics, the downside of dogs—other than Bambi and Chico, of course—was a predictable topic of conversation between the two men.

Their shared negative attitude toward dogs stemmed from dogs barking and roaming at will (because ordinances never got enforced), peeing and pooping wherever they pleased, and plodding with heavy paws through the gardens.

My own dislike for dogs grew more out of fear. When I was barely five years old, I’d followed my older sisters over to the Caine’s one day when the parents were gone. At the time, one of Caine’s dog was an all-beige cocker spaniel named “Spooky.” I happened to want to exit the house just as Mrs. Caine was pulling up in the long driveway. All wound up over her return, Spooky barked, tore in front of me, and put his paws up on the door to give himself a better view. When I pulled him back by the collar, he leapt at my face and nipped me in my lower lip. I wasn’t seriously hurt, but the encounter scared the bejeezus out of me, and for a long time after that, I was skittish around dogs.

My disposition was aggravated by Caine’s other dog, a black lab named “Stormy.” In reality, Stormy was harmless, but to a young kid, a big, black, frisky dog with that name appears to be anything but harmless. And Caine’s let Stormy run freely around the neighborhood.

On one otherwise perfectly pleasant day, my fear of Stormy turned to anger and outright contempt. Lunchtime found me playing out in the driveway when we still lived in the old house right across from the Caines. Not wanting to interrupt my contentment, Mother had fixed a peanut butter and jelly sandwich, cut it in half, put it on a plate and placed it, along with a glass of milk, just outside the back door. I helped myself to one half of the sandwich and nibbled at it while I walked around on the driveway. Somehow, Stormy appeared without my seeing him. I turned, and to my horror, the black beast was between me and the safety of the back door. I froze. No one could save me. Not Mother, not Dad, not my older sisters. No one. I was about to die.

However, Stormy did not attack me. He didn’t even seem interested in me. Instead, he went for my sandwich, shoving his big, wet snout into the Wonderbread. Then he did the really despicable. He went for the milk. He dropped his heavy, red tongue into the glass and started lapping it up, then dumped the glass over, spilling the rest of the milk down over the steps. My abject fear turned to outright disgust and anger. Stormy, the unruly agent of terror had crossed the line.

“Git!” I yelled, imitating Dad. Stormy took a look at me, let his milk-laced drool slide off his tongue and dashed off.

Thus, when Dad and Fred exchanged mutual vitriol about barking dogs, I found it easy to embrace their open dislike of other men’s best friends. But somehow, like Dad, I was able to separate a well-written story about a well-trained collie from the idea of owning a dog, particularly an unruly Labrador, which was the most prominent example in our neighborhood.

* * *

Jenny’s infatuation with collies was untainted by my encounters with Spooky and Stormy and my exposure to Dad’s exchanges with Fred. And perhaps she had seen more TV episodes of Lassie at her friends’ houses than I had watched at my friends’ homes—our family didn’t own a television, so any exposure we had to that medium was limited to what we saw in other homes and on our grandparents’ TV during our Sunday gatherings at their house during the school year.

Jenny and Mother were very close, and Jenny’s whimsically colorful imagination found easy encouragement with Mother. Together they embarked on a search for collie breeders. I don’t remember all the details, because for whatever reason, I did not participate at all in the process. What I do remember is that over the supper table, they mentioned bits of information about their search for a collie and that in no uncertain terms, Dad poured cold water on the whole idea.

“I don’t want a big, hairy, slobbering dog inside this house, and I don’t want a big barking dog in my yard,” he’d say. In case any doubt remained, he’d add abundant detail. “They water all the flowers, they crap on the grass that I’m trying to keep green and nice looking, they shed their filthy hair all over everything, they drip long strands of saliva wherever they go. They can’t be allowed to run all over the neighborhood, so where ya gonna put the darn dog? In the garage? In the basement? In some kind of kennel? And who’s gonna have ta build a kennel? And how ya gonna prevent it from barking and keeping all the neighbors awake at night? And what are ya gonna do when ya wanna go on vacation or up to the cabin? Take the dog with? Ya can’t have a dog slobbering all over the inside of the car. No, I’ve got enough problems without havin’ a dog to worry about.” And so on.

Dad’s indictment of dogs was always directed at Mother, which is why her encouragement of Jenny’s desire was furtive and conflicted: Mother knew that Dad always meant what he said, and once he said it, he never changed his mind.

But if Mother was resigned to the impossibility of getting a collie, Jenny’s wishful imagination was matched by unshakable determination.

* * *

“There’s no way Dad’s gonna let you get a collie,” I said after she’d snatched back her written entreaty to Dad back on that day in July 1967.

“Yes he will!”

“No he won’t.”

“Yes he will.”

“Dad’s no means no, little girl.”

“Not when he sees my letter!”

I’m not sure why I was so contemptuous of my younger, innocent sister. Maybe my bullying was in response to the inferiority I felt vis-à-vis our older sisters, who were so smart and self-assured, such high-achievers in school, such better violinists than anyone in town or at the violin studio down in Minneapolis where we all took lessons, and certainly better than their kid brother, who hated the instrument but had been forced to practice it enough to know how hard it was to play. Jenny was plenty smart—I couldn’t deny that—but she was not yet as proficient on the violin as I was. Her vocabulary was big, but she wasn’t old enough yet to be taken seriously. Plus, she couldn’t throw a baseball or swing a bat and hit anything. I could demonstrate my superiority over her so I did.

I exited her room, slamming the door to underscore my contempt for her naiveté.

* * *

I was throwing a tennis ball against the garage door and catching grounders when Dad pulled into the driveway in his black, 1962 Buick Electra sedan. It was the nicest car he’d ever owned but he’d bought it used at a good discount from one of the judges and for cash. I greeted him as he emerged from the car, pulling his suit coat and brief case after him.

“Hi, Dad.”

“Hi. Anything constructive happen today?”

“I watered the lawn, and my baseball cards got organized.”

“I’m paying you to water the lawn,” Dad said. “Did your violin practicing get organized?”

“Not yet.”

For years running, the violin had been a contentious subject between my parents and me. My three sisters couldn’t get enough of the violin. I, on the other hand, hated practicing, and I resented my parents’ insistence that I sacrifice a half hour of “outdoor time” every day. With Dad’s inquiry about practicing that day, I quickly tried to change the subject. “Jenny still thinks she’s gettin’ a dog.” I said. It worked.

“Oh yeah?” Dad said, stepping toward the lawn to conduct his routine inspection. In the summer it was the first thing he’d do after pulling into the driveway from work. “The last thing we’re getting is a dog,” he said, as he surveyed the front lawn. “We’d get a TV before we’d ever get a dog.”

“Are we getting one?”

“Huh? Getting what?” Dad asked as he looked up and down at the grass.

“A TV.”

“No. No dog and no TV,” Dad said.

I left him to his inspection and went indoors. Holding his suit coat over his shoulder, he eyed the green carpet in which he took pride. He noticed a late-blooming dandelion nudging its yellow mane above the well-trimmed grass.

Dad walked to the infiltrator, bent over and pulled it out by its taproot. Now on high alert, he crouched to survey the surrounding territory more carefully for less obvious incursions. His concentration was interrupted by a familiar voice.

“Can’t believe you let a dandelion invade the Republic of Raymond,” said Fred as he approached across the street.

Surprised, Dad stood up and moved toward the curb to greet Fred. “Hi, Fred,” he said, tossing the dandelion into the street. “Ya, well, LBJ can’t seem to completely boot the communists out of South Vietnam, either.”

“Ya know,” said Fred, “in sixty-four, people told me if I voted for Goldwater, we’d get four more years of war. They were right. I voted for Goldwater, and here we are—three years later with no end in sight to the war.”

“We’re in a mess over there,” Dad said. “Whether a guy is fightin’ communists or dandelions, he’s gotta use the right amount of weed killer, and Johnson’s not usin’ enough weed killer.”

Their voices had faintly carried past the front screen door and down the hallway to the kitchen where Mother was transferring food to serving dishes. She’d sent me out to summon Dad. I stood at the doorway and waited for an opening in Dad’s exchange with Fred.

“Say, dja hear Caine’s dog barkin’ again last night?” I heard Fred say.

“Darn dog,” said Dad. “I was gonna call the police this time, but then all of a sudden it stopped.”

Fred laughed. “Ya know why?”

“Why?” said Dad.

“’Cuz I barked back.”

“You barked back?”

“I called and let it ring four, five times before big ol’ Bill picked up the phone. When he did, I went, ‘woof, woof, woof,’ just like that, and hung up.”

“Serves ‘im right!” Dad said, shaking his head in amusement. “Darn dog. I don’t know where people get the idea they can keep big dogs in town . . . barking all hours of the night, running loose, wreakin’ havoc on people’s lawns. Where’s the dog-catcher when you need ‘im?”

“Forget the dog-catcher, Ray. Just call Bill Caine at two in the morning and bark.”

Dad and Fred laughed together, which signaled my opening. I pushed on the screen door and called out. “Dad, supper’s ready . . . Hi, Mr. Moore!” Fred waved at me.

“I’d better go too. Just got home,” he said to Dad. “See ya Ray.” With that, Fred turned back toward his yard. Dad bade him good-bye and approached the house.

* * *

Dad pulled an LP out of his tightly packed collection. The albums occupied the cabinet under the pull-out turntable of the hi-fi. To house an amp, tuner, speakers and turntable, all of which Dad himself had installed, he’d had the contractor build a kind of station between the dining room and the living room. Every evening after inspecting the lawn, the first thing Dad would do was flip the switch on the amp, put a record on the turntable and fill the downstairs of the house with classical music. If it wasn’t in the piano repertoire, with which Mother was nearly as familiar as was Dad, or a well-known symphony, he’d make her guess who the composer was.

On that particular evening, the music was of a string quartet. “Know who this is?” He asked.

“Haydn?” she said, as she delivered a bowl of over-cooked string beans to the table. By this time my sisters and I were taking our seats.

“Close,” Dad said. “Early Beethoven.”

Dad then walked around to his place at the head of the table. As he drew his chair back, his eyes settled on the envelope that Jenny had placed on his dinner plate. “Well, well, what do we have here?”

As Dad picked up his dinner knife to slice open the envelope as neatly as possible, I could feel Jenny’s eager look from her place to my right. My sight was on Dad too. As he moved his eyes left and right and down the page, I saw his countenance change from curious to amused to revealing the hint of some version of “yes.”

“Well, Jenny Wren” he allowed, using his term of endearment for his youngest child. He carefully folded up the letter and inserted it back in the envelope. “Does someone wanna pass me the meatloaf?”

“Well what?” asked Jenny.

“Well, I’m thinking hard about it,” said Dad. “Potatoes please.” He held to a faint smile, as we all waited for his verdict. “Thanks,” he said, as he received a bowl of baked potatoes from Elsa around the table corner on his left. “Beans, please.

Dad assembled the food on his plate and applied his usual choice of condiments in gracefully measured fashion. The care that he assigned to the mundane task reminded me of our grandmother, who had died earlier in the year. The time consumed by his habitual meticulousness gave Dad a chance to formulate conditions. Held in suspense, I managed a sideways glance at Jenny. She was ready to burst with joy.

“Here’s what I’m willing to do,” Dad said finally, addressing Mother as much as Jenny.

“You and your mother can get a dog, but . . .”

“I knew it, I knew it!” Jenny cried. “Mommy, I knew it! I knew Daddy would say yes!” All that Jenny heard, of course, was what preceded “but.” In retrospect, I think Mother must have been shocked. I too had assigned a very low probability to Jenny getting her way. I knew and feared Dad’s judgments and certitude, but I also wanted Jenny to fail in her entreaties to Dad. Her failure would bolster my need for feelings of superiority over her.

Dad proceeded to lay down his conditions. First, the collie had to be full grown—puppies were way to frisky and therefore, way too much work for a nine-year old and her mother. Second, the dog would not be permitted ever to enter the house; accordingly, before the dog could appear on our property, he, Dad, would have to design and build a proper kennel and doghouse. Third, the dog could not be from a kennel—too expensive for Dad’s Swedish frugality.

* * *

While Mother and Jenny took care of the dishes, Kristina and Elsa resumed their violin practicing upstairs. I sat on the living room floor organizing my baseball cards, while Dad, sitting nearby, read the day’s edition of the Minneapolis Star. After giving it 20 minutes, he got up and walked out to place the paper atop the stack of newspapers in the garage. Moments later, Mother retrieved the paper, and with Jenny at her side, spread it on the dining room table.

“Let’s see what’s in the want ads,” said, Mother. Before Mother could turn to the classifieds section, the front-page headline caught Jenny’s eye. “McNAMARA IN SAIGON FOR FATEFUL TALKS.”

“What’s that about, Mommy?” she asked.

“Oh, nothing,” Mother said, turning the page as fast as she could. “Nothing that concerns us.” She kept turning pages, sections, until reaching the classifieds. She ran her finger down a couple of columns. “No dogs for sale today, I’m afraid.”

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2023 by Eric Nilsson