NOVEMBER 18, 2023

FAILING THE GRADE

ANOKA, MN – SEPTEMBER 1967 – END OF AUGUST 1968

Dad loved history and politics, which is probably why from an early age, I loved both too. Dad subscribed to American Heritage magazine, and by the time I reached my teens, years of bi-monthly, hard-bound editions had accumulated on the bottom shelves of the floor-to-wall shelves of the den. Dad had also acquired American Heritage volumes dedicated to the American Civil War, World War I and World War II. On gray, gloomy days, when I was pretty much bored with other pursuits, I’d sit on the den sofa, switch on the wall lamp above it and pore over those American Heritage treasures. Dad’s library contained lots of other history books, and when I was as young as eight, he’d read aloud to me from William Prescott’s Conquest of Peru and Conquest of Mexico.

Beginning in the mid-1960s, Dad subscribed to a weekly newspaper called Human Events. Not only did he read each issue, front to back; he wound up subscribing indiscriminately to its unwavering rightwing slant on things. He even fell for the scams and scare tactics of some of its advertisers—“get above-market rates on commercial paper issued by the ‘American Board of Trade’”; “Get Ready for the Coming Stock Market Crash!”; “How to Feed Your Family When Everyone Else is Starving” to name a few.

I don’t know how Dad heard about Human Events in the first place, but it certainly shaped his worldview. For years before Human Events, he’d been a subscriber to the monthly newsletter of the American Enterprise Institute, a Libertarian think tank. Those newsletters featured headlines that were far less conspiratorial and sensationalist than the ones in Human Events, and each issue was dedicated to a single article, usually concerning economic theory, and was not cheapened by any advertising. If perhaps the publisher of Human Events had purchased a mailing list from the American Enterprise Institute, thus explaining how Dad had gotten snagged by the rightwing, fear-mongering, I have no theory as to how Dad had been roped in by the more respectable organ of the more dignified, intellectually sober Libertarians.

To the extent my paternal grandparents were political, they were probably Democrats. I remember Grandpa praising Hubert Humphrey when the Minneapolis Star featured the Happy Warrior’s picture visiting wreckage wrought by a string of tornadoes on a single night just south of Anoka in the spring of 1966. And my great-grandpa Johan Nilsson, a Swedish immigrant who worked 12-hour days as a Minneapolis streetcar conductor, was most decidedly to the left of Hubert Humphrey: when Dad cleaned out my grandparents’ big old house near the university campus, which they had moved into after the death of Johan, Dad found in the attic, a huge framed portrait of none other than . . . Karl Marx.

Perhaps Dad had been influenced by some conservative judge—for years, I knew, Dad had lunch every day with “the judges.” Or maybe it was Fred Moore, whose archly conservative views were part of nearly every conversation, who influenced Dad.

Dad’s worldview, which Mother had little choice but to adopt, got plenty of air time in the course of family conversations over the supper table. And if Dad’s regurgitation of agit-prop material from Human Events wasn’t enough, my oldest sister, Kristina, had fallen in love with Ayn Rand. The dye was cast as far as my own views were concerned.

Upon entering the eighth grade at Anoka Junior High School, I was, like any of my classmates, buffeted by the conflicting forces of family, societal and adolescent influences. In many ways, I learned to fit in, but in other ways I didn’t. Thanks to my older sisters tuning in KDWB and WDGY, the two rock ‘n roll stations in our market, I knew the Top 40, but because our family still didn’t have a TV, I lacked exposure to many aspects of popular culture, including team sports[1]. I knew most of the “cool” kids at school but never got invited to any of their parties. I had a range of solid friendships, but hung out mostly with two or three kids with whom I shared a common interest in track and cross-country, downhill skiing, and who were academically inclined—a sure-fire way to exclude yourself from the “coolest” kids. Where your “coolness” as a male was signaled primarily by your clothes, most particularly your shoes—loafers, English walkers, or Jack Purcell sneakers—I had decent clothes but was never able to talk Mother into buying me the “cool” shoes, which according to her were “more expensive than they needed to be.”

Since I didn’t wrestle, play hockey or basketball, the only school-sponsored winter sports back then, I sat out the school winter sports season. And because no one rode bikes in the winter, from November through March, I didn’t see much of my friends after school, since they all lived on the other side of town.

Thus, for much of the school year, after classes each day, I hiked home alone. After changing clothes, I loved to go back to Björn’s kennel, and let him chase around the yard for a while. Once the Mississippi froze, a whole new world opened up.

As far back as I can remember, I had embraced winter. I could never get enough of it, and somewhere along the line my love of cold and snow led to binge-reading about arctic and Antarctic explorers—Scott, Byrd, Shackleton, and Amundsen, among others. In a biography of Raould Amundsen, I’d read that when he was at home, to stay acclimated to cold weather he’d sleep with the windows wide open throughout the year. One night when the mercury dropped to around 20-below Fahrenheit, I thought I’d emulate Amundsen. I opened both windows in my bedroom—all the way—and climbed into bed. When Dad later came up the staircase and felt an icy draft pouring out under the door, he opened it and exclaimed, “What the sam hill is going on in here?” The windows got closed before I got out of bed.

To my delight, the winter of 1967-68 was the kind that made Minnesota famous. Nowadays, the Mississippi rarely freezes over for long, but that winter the ice was plenty thick. Each afternoon after school I’d take Björn on a long hike up the river. I imagined myself as a solo arctic explorer with my trusted dog, aiming always for the North Pole. Landmarks along the way counted as geographic features on the map—Jackson’s Island, long and narrow and about a mile upstream, was Ellesmere Island; the farmland beyond it was the north part of Russia. In the middle of the river ice between those two places was—the North Pole.

I liked these expeditions best when the air was coldest. Wearing a hooded parka, a woolen hat under the hood, snow pants, “chopper” mittens, several pairs of socks and a pair of insulated “Pac” boots, I could press into the worst that Mother Nature cared to hurl at me. Björn, ever ready for my treks, would point his head into the cold and match me stride for stride. We made a tight pair of explorers.

Often we’d take two treks a day—one after school and another shortly following supper. After the second one, I’d let him wait inside the garage while I prepared his meal. For 13 years the routine didn’t vary—a few cups of Purina Dog Chow, a small Pyrex dish of liquid bacon fat (saved from Dad’s breakfast) poured over the top of the dry dog food, and a Milk Bone laid on top. On really cold nights, I’d slip his meal bowl and his water bowl inside his spacious doghouse so that he could eat in relative warmth and to prevent the water bowl from becoming a cake of ice.

Every meal was “set” the same: I’d let Björn out onto the top of the back steps behind the garage, then walk his dinner and his water bowl down to the kennel. I’d trained Björn to stay seated on the back steps until I gave the command. Often I’d test him—or maybe it was tease him, just a little—by waiting a few seconds. He’d bob his head and lean left, then right, anticipating the call but never once leaving the steps until I gave the word. But once I shouted, “Okay, Björn!” He’d fly off the steps and sprint as fast as a greyhound across the backyard to the kennel.

On one occasion, I made a terrible mistake. I’d changed up my routine and put the meal dish inside the kennel but not yet the water dish. Most critically, upon leaving the kennel I’d pulled the gate closed to make a minor adjustment to it but inadvertently left it closed. As I stepped away from the kennel and headed toward the house to replenish Björn’s water, I gave him the command. He bolted, as usual, but seconds later, in the dark, he ran smack into the closed gate. The impact left him stunned.

Björn staggered as I dropped the water dish and chased down to the kennel to see if he was okay.

“Björn!” I cried. “I’m so, so sorry! “ I dropped my knees in the snow in front of him and grabbed the long fur on each side of his head. In short order, with a wagging tail he reassured me that he was okay. Never so quickly had a human ever granted me a reprieve for such a thoughtless ransgression.

Dad certainly granted me no reprieve when reviewing my report card in March 1968.

* * *

While Mother put food dishes on the table and Jenny and I took our seats (our two older sisters were away at school), Dad put a record on the turntable. As Rubinstein started in on Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 17, Mother and Dad joined us. Seeing a report card next to his plate, Dad opened it, then helped himself to a generous serving of hotdish—one of three in Mother’s repertoire. He then examined the report card.

“Good work, Jenny wren,” he said. Not surprisingly, her marks were good enough for Dad to invoke his term of endearment for her.

“And where’s your report card, Eric?”

“Uh, Ray,” Mother answered, “can we talk about that after dinner—just the three of us?”

I could feel Dad’s eyes stabbing me. I knew better than to look back at him.

“Thank you for trying not to ruin my supper,” he said, “but I think you have.”

After pushing my food around my plate, I tried to eat some. I forgot how hungry I’d been before supper. When the meal was over, I found myself sitting on the sofa in the den, doors closed, with Mother sitting dutifully in a chair and Dad standing over me. Then he started in.

“A ‘C’ in history? A ‘D’ in geography? An incomplete in orchestra because— because why? Because here it says, ‘Eric was absent from numerous rehearsals and winter concert’? What in the world is going on here?”

Did he really want to hear the truth? But what truth was I prepared to tell? That I hated school? That I hated every single one of my teachers except algebra and English? That I hated the violin? Didn’t he already know that? Of course he did! Why was I being tortured like this? Why couldn’t I just . . . just what? I wanted to get up, leave the house and take Björn on a very long walk. In the end, I chickened out. “Uh, I got ‘B’s in math and English,” I said lamely.

“What?” Dad shouted. He was really getting ramped up. “Since when did anyone in this family take pride in a ‘B’?” I didn’t have an answer, I just had resentment.

“Why can’t you be like your sisters? They study, they practice, they follow the rules. They’re going to amount to something. And you? You’re the only son of an only son of an only son. And so far, you’re the only one to get bad grades. Do you think your grandparents came all the way over here from Sweden so that their grandson, the crown prince of the family, could be a failure? What in the sam hill is your explanation?”

When Dad was officially mad, he used, “sam hill,” but I didn’t know what that meant exactly, except maybe he was saying “sand hill,” and that didn’t make much sense either. It was in the course of that outburst over my eighth grade academic performance that I learned to translate “sam hill’ as just plain “hell.”

Though I was unfamiliar with the term “rhetorical question,” I knew that Dad’s question was exactly that. Nonetheless, I wanted to try an explanation. “Uh . . .”

Dad cut me off. “On second thought, I don’t want your explanation, because there is none.” Dad’s eyes bulged and the corners of his mouth turned downward. “So here’s what’s going to happen,” he continued.

“What?” I said, barely managing to be audible.

“You’re going away to school next year, that’s what.”

“Ray!” Mother said. She moved for the first time since the start of Dad’s tirade.

“I’m not leaving Björn,” I said, keeping my head down. I wanted Dad to know how angry I was, but I didn’t want him to see the tears that were welling up in my eyes.

“You have no choice,” Dad said, letting fly with a little spit on the “ch.” “And along with your dog, you can leave your violin. You’re done with that because I’m done with that.” As Dad grabbed the doorknob to let himself out, he threw me a zinger. “Because,” he said, “I’m done with your failures.”

* * *

By late August, the decision was in: I’d be attending Sterling School in the hamlet of Craftsbury Common, tucked away in the Northeast Kingdom of Vermont, a million miles away. The school was a classic New England boarding school for boys, grades nine through twelve, with a total enrollment of 100 students, which didn’t quite double the population of Craftsbury Common, which was 150.

Amazingly, Mother and Dad made the decision based on telephone call with the director of admissions and a glossy, three-panel brochure sporting three black-and-white photos of the campus, a brief history of the school and a summary of its mission to provide a quality academic education and plenty of outdoor sports and other “open air” activities. The school was recommended by my seventh-grade guidance counselor at Anoka Junior High. Some genius from Sterling had acquired an early notion of the desirability of “diversity,” which, in his mind meant geographic diversity—the overwhelming number of students hailed from New England, New York and New Jersey. I was admitted based on an in-person interview with the director of admissions who ventured out to Minnesota in early August—and a writing sample.

* * *

With the written instructions in hand, Mother had taken me into Hilliard’s in downtown Anoka to outfit me for school—including, “navy blue blazer, two additional conservative blazers or suits, three dress shirt and selection of ties.” Feeling a bit stiff and awkward in my new clothes, I walked to kennel to bid farewell to Björn. I sensed that he knew something was up. The vigorous tail-wagging was accompanied by an uncharacteristic series of soft whines. He dutifully sat on command and lifted his right paw to shake.

“Okay, Björn, time to say good-bye,” I said, barely maintaining my composure. I didn’t want Björn to see me lose it. “You be a good dog, ya hear? Be good ’cause Dad’s gonna take care of you while I’m gone, and I don’t wanna hafta worry about you, okay? Don’t bark too much either, and when Dad shouts ‘quiet,’ you’re gonna have to be quiet, ’cause Dad can’t stand barking, okay?”

I burst into tears and gave him as big a hug as I my strait jacket-blazer would allow.

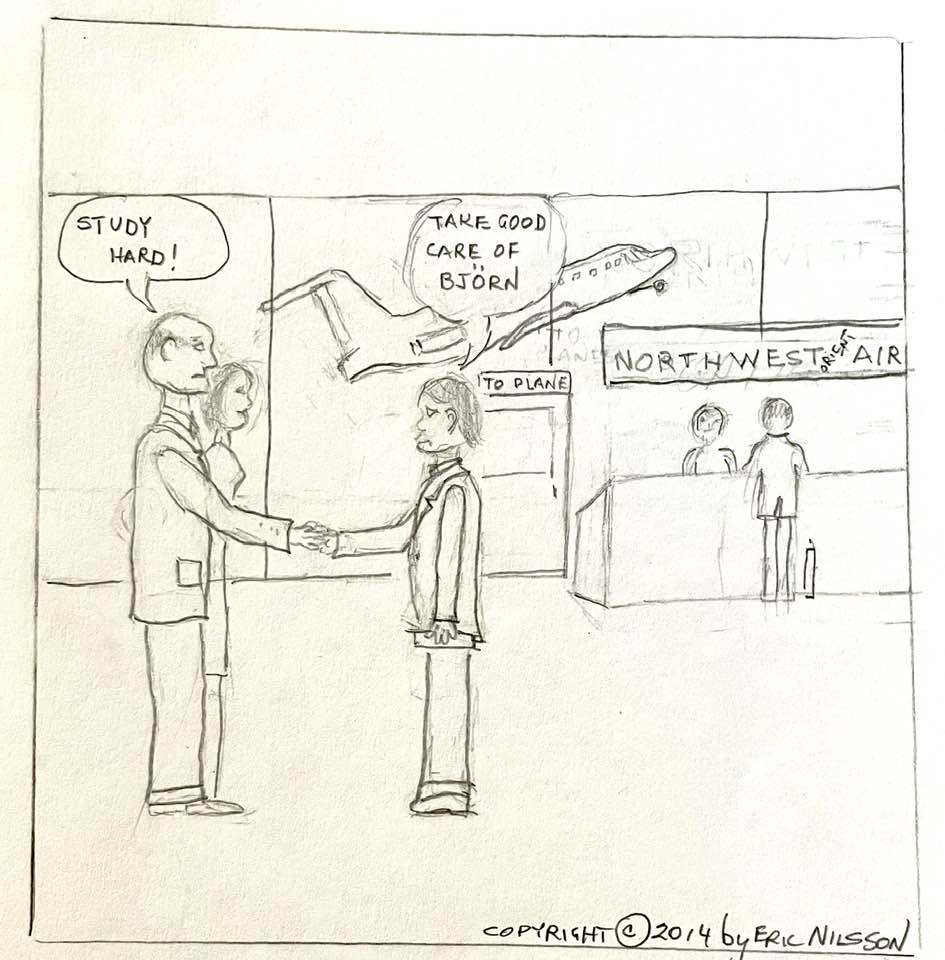

“Come on, let’s go!” Dad shouted from the back steps. “You don’t want to be late for your flight.” I said my final good-bye to the last friend I seemed to have. By the time I reached the driveway, Dad was lifting my duffle bag into the trunk. A tacit understanding had been reached that my violin case would not be accompanying me on the trek to the Craftsbury Common in the Northeast Kingdom of Vermont, where Sterling School was located.

When Dad saw the white and tan dog hair on my blue blazer, he put a hold on our departure. “For crying out loud, you can’t go looking like that,” he said. Under his breath he added, “Damn dog.” As much as I hated to leave Björn, now I couldn’t wait to leave home. Dad hurried back into the house to retrieve the lint roller that he used on his fedora and stored on the shelf in the downstairs closet. After what seemed like an excessive effort, I was cleared for take-off.

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2023 by Eric Nilsson

[1] Dad detested the popular culture’s infatuation with team sports, though he unwittingly made me a fanatic fan of major league baseball. When I was in fourth grade, someone gave Dad two tickets for prime seats behind the first base dugout at the old Metropolitan stadium. Thinking it would be a fun father-son outing, he took me to the game. It was that game—a lack-luster loss by the Twins, ironically—that sparked my own infatuation with the sport.