NOVEMBER 14, 2023

MELTDOWN

ANOKA, MN – AUGUST 15, 1967 AFTER ABOUT 5:15 P.M.

Just then, Jenny was helping Mother set the table. The sound of two violins—one playing scales, the other Bach—emanated faintly from the floor above. Standing at the edge of the dining room, I heard Dad enter the house and his shoes striking the tiled hallway back to the kitchen. He then appeared in the doorway into the dining room. He was not wearing his friendly face.

“Hi, Ray,” Mother said. “Supper’s just about to come out of the oven.”

“Good, ’cause otherwise, given the day I had I’d be fixin’ myself a drink.” Dad rarely drank. The only time I saw him drink-drink was up at the lake. After a hard day of physical labor associated with one project or another, he’d sit out front with Grandpa and have a Hamm’s out of the can while discussing some aspect of the project. And twice a year—after Dad and Grandpa, with the help of Carl Hanson, builder of the cabin, had put the dock in and after they’d taken it out—he’d drink one shot of whiskey from the bottle of Old Crow that Grandpa stored in the back of one of the floor-level cabinets in the kitchen. To be sure, a small liquor cabinet existed above the refrigerator in our house, but rarely did a bottle come out. Only on one of the seldom occasions when Dad hosted a home cocktail hour for his deputies and the judges—or after a particularly stressful day at the office—was the liquor cabinet opened.

“The dog arrived today,” Mother said, in what I saw as an attempt to change Dad’s mood without having to learn what had created it.

Dad tossed his suit coat on the sofa and squatted down in front of the record cabinet to pick through the albums. He was still pre-occupied. “Huh?” he said, pulling out an album. “Oh ya, that was today.” He slipped the LP out of its jacket and stood up. “Any disasters yet?” he said. For all his positive qualities, Dad could be unsettlingly negative, especially when he was upset.

“He went wee-wee on my leg,” said Jenny, as she laid down the last of the silverware, “and he’s scary and I don’t know if he’s mine anymore.” I was always amazed by Jenny’s candor. People say that she is the one most like our blue-blooded, maternal grandmother out in New Jersey, who, later in life, was described by Elsa as a cross between Queen Victoria and Winston Churchill. But on this occasion, Jenny’s candidness did not serve us well.

“The dog is a bit much, Ray,” said Mother, trying to blunt Jenny’s remark. “Unruly, really.”

Mother meant well, but her attempt was counterproductive. Dad dropped the record onto the turntable from an angrily reckless height.

“Unruly? Did you say unruly?” Dad’s eyes were bulging as his lower lip curled. “You two twist my arm to let you get a dog, a big dog; you promise that I won’t have to take care of it, and here we are, less than a day into the ordeal when you break your promise. And now we’re stuck with an unruly dog no one wants. Great. That’s just great.”

“Honey, I’m sorry.

“Sorry?” Dad said, forgetting that he hadn’t yet turned the music on. “Yeah, well I’m sorry too.”

“Honey, maybe . . .”

“Maybe nothing. I laid down my rules and they’ve been broken before the darn dog has been here one darn day.”

Bursting into tears and painful cry, Jenny ran past me and out of the room. While Mother and Dad argued, or more precisely, while Dad harangued and Mother tried to calm him down, I followed Jenny up the stairs as she rounded the top of the staircase. I barely noticed the violin practicing that raged behind the closed door of each of two facing bedrooms. Just as I reached the second floor, I saw Jenny whip down the hallway to her bedroom, where she charged in and slammed the door. The violin playing stopped abruptly, and almost simultaneously, Elsa and Kristina each opened their doors to see what the commotion was all about.

“What’s goin’ on?” asked Elsa.

“I’m tryin’ to stop everyone from barking,” I said, striding down to Jenny’s room. Once at the door, I heard Jenny’s muffled crying. When the doors down the hall closed again and the violin practicing resumed, I tapped on Jenny’s door. When she didn’t respond, I opened the door slowly. Jenny was lying face down on her bed, sobbing into the pillow.

“Go away!” I heard her muffled voice. “I don’t wanna see anyone.”

Maybe for the first time ever, I felt sorry for my younger sister. Another emotion mingled with sympathy, though I couldn’t quite identify what it was. In retrospect, I think it was a twinge of guilt for how much I’d teased her about her naïve infatuation with the idea of getting a collie. Her innocent dream was becoming a nightmare.

“I’m . . . sorry,” I said.

“Sorry about what?” I heard her say. “That I’m a dirty rotten person?”

“Huh?” I said, unprepared for what she’d said.

“I’m the one who’s sorry,” Jenny said to me, now sitting up and peering at me, her face flush with emotion. “I feel sorry for Mother because Dad’s mad at ‘er. I feel sorry for Dad ’cause he didn’t want the dog to begin with, and now they’re probably going to get divorced like my friend Sarah’s mom and dad, and I feel sorry for the man who sold us the dog ’cause it made him sad and now we can’t even keep the dog, and I feel sorry for myself ’cause I’m so sad.”

It was quite a speech, and I hesitated. I couldn’t summon the words and put them in order quickly enough. “Wull . . .” I said, awkwardly, “maybe it’s not as bad as you think.” It was the best I could come up with, and it felt like a lie. I hadn’t thought of the possibility of Mother and Dad getting divorced over the dog.

“What do you mean it’s not as bad?” Jenny said, burying her face back into the pillow.” She seemed inconsolable, and I was feeling awful.

“I think I can make sure Mother and Dad won’t get divorced,” I said. I had seen them argue before, and as unsettling as those occasional episodes could be, I knew that inevitably, our parents managed to patch things up again, and in fairly short order. But this time the circumstances were uniquely challenging.

“How?” Jenny said, lifting her face just high and briefly enough to be heard.

“I can take care of the dog,” I said.

“What?” Jenny said. A rivulet of tears still ran down each side of her face.

I knew she heard me but didn’t believe me and was putting me to the test. I didn’t quite believe myself either.

“I said I can take care of Björn,” I said, as much to myself as to Jenny.

“But do you know how?” she asked.

“I’ll go to the library and get some books on dog training,” I said, dodging the truth. “I’m gonna make it all okay.” I meant it.

“Really?” With both hands, Jenny wiped her tear-washed face.

“Yeah.”

Jenny had stopped crying, but her post-crying breathing spasms continued. “Ok-k-kay,” she said. “Can you tell Dad?”

“Yeah, I’ll go tell ‘im now.”

Oblivious to Jenny’s distress and my commitment to alleviate it, Elsa and Kristina continued their practicing and Mother and Dad, their arguing. With a combination of trepidation and sense of necessity, I descended the staircase and walked into the living room, where the intensity of our parents’ exchange had more space.

“Uh, Dad?” I cut in. The arguing stopped.

“Wha-a-t,” Dad said, without inflection.

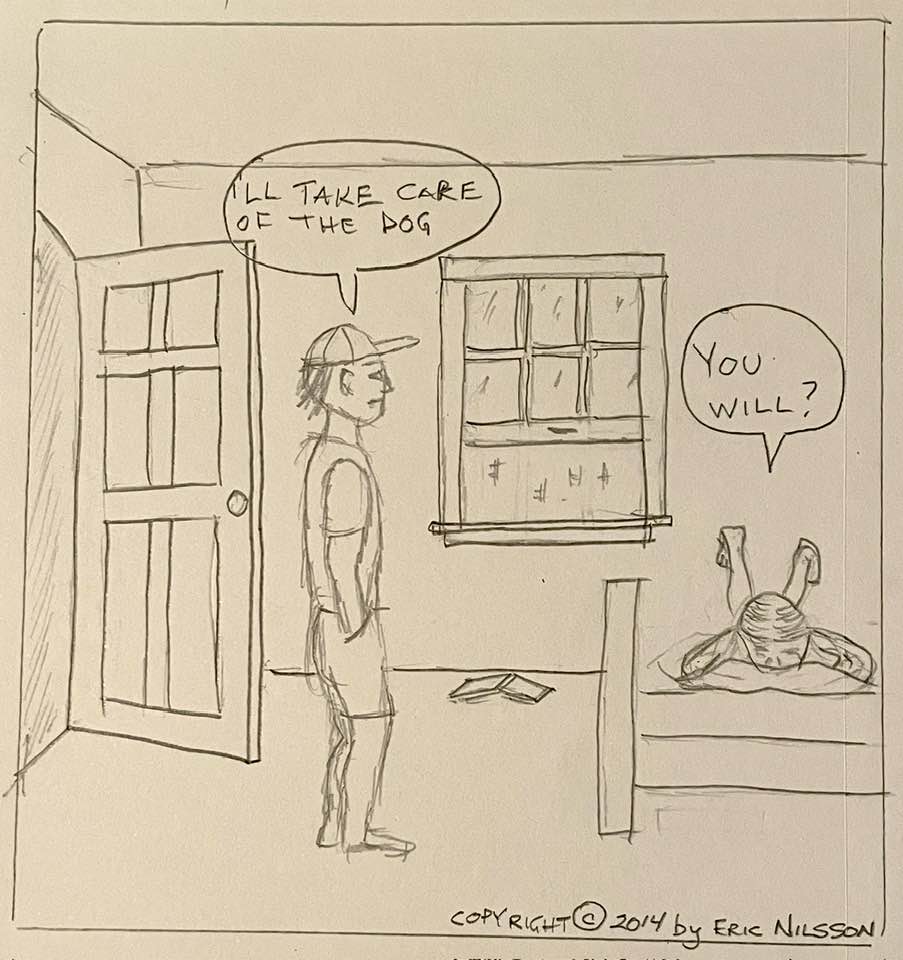

“I’ll take care of the dog,” I said.

“You will?” In his tone detected both surprise and skepticism.

“Yeah. I’ll take care of him,” I said, gaining confidence. “And I’ll learn how to train him so he won’t be so wild.”

Mother saw an opening. “Let me put supper on the table,” she said, scurrying away to the kitchen. “Tell the girls it’s time to eat.”

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2023 by Eric Nilsson