NOVEMBER 21, 2023

“ONE SMALL STEP FOR A MAN . . .”

ANOKA, MINNESOTA – JULY 1969

Dad exited the courthouse and walked to his Buick Special, parked in the adjoining lot. The blue sedan was his first ever brand new car, but it was a base model with no frills. He had negotiated the price down as far as he could, then paid cash.

* * *

On the open highway, Dad drove fast, and he was not afraid to pass on the two-lane country roads on the route up to the lake. In town, however, he never gunned the car from a dead stop. “You should think of your car as a horse,” he explained to me. “You wouldn’t dig your heels into your horse and expect it to take off at a gallop. First you’d ease ‘im into a walk, then a trot, then open ‘im up. Same way with a car. You shouldn’t stomp on the gas. Your car’ll last a lot longer if you go easy on it, if you accelerate gradually.” I think of Dad and his horse analogy whenever I encounter a stop sign or red light.

To my knowledge, Dad had limited experience with horses. His only riding experience that I knew about was the one at Fred Moore’s hobby farm in the open country on other side of the Mississippi. Moores owned two or three horses, which they stabled in an old barn on the hobby farm. One warm summer evening in July 1960, they invited our family out for some horseback rides.

Mother used to take us horseback riding, so she was perfectly comfortable riding “Goldie,” the mild-mannered mare. Dad, meanwhile, was assigned to the gelding, which, as it turned out, was not so mild-mannered. No sooner had Fred helped Dad mount the horse inside the fenced in walking area behind the barn, than the animal charged off, going from zero to breakneck speed faster than Dad could say, “Whoa!” Horse and rider headed straight for a high fence 200 feet away. Dad later told me that he ran a quick calculation—jump off and suffer certain injury or hang on for dear life and hope for the best. As the decision window closed with life and limb hanging on the ledge, Dad made his choice. He’d stay with the horse.

“Best” turned out to be better than he could have hoped. At the very last moment, instead of leaping over the fence and either tossing Dad in the air or taking him on a wild chase over the countryside, the horse made a sharp right-hand turn, then trotted back to where we all were watching in disbelief. White faced, Fred grabbed the horse’s halter as Dad climbed down from his short but thrilling ride.

“Wow!” Dad said, as he pulled out a handkerchief and wiped the sweat off his bald pate. “That felt like a rocket ride to the moon!”

“Must’ve been the Russians who got into our stash of sugar cubes,” said Fred, laughing with Dad. I’d heard them laugh before, and this time, it was nervous laughter, replete with relief.

* * *

Dad eased the Buick Special into a parking slot in front of Joe Chutich’s Western Auto store a couple of blocks from the courthouse. He got out, walked in, and approached the counter, manned by Joe.

“Hi, Ray,” said the hardware man. Joe had owned the store since the beginning of time and was always on hand. Dad returned the greeting.

“What can I get you?” said Joe.

“I wanna rent a TV for the moon landing,” Dad said.

“You betcha.” Joe lifted a small one from a shelf behind the counter and placed it next the cash register. “I got this here one,” said Joe. “On the small side but easy to carry.”

“Hmm,” Dad returned. “I should probably get one size up, Joe. Whole family’s gonna be watching.”

Joe put the small one back on the shelf and reached for a slightly larger one. “We got this one here,” he said. “A Sylvania.” Joe watched Dad give the TV a close look and saw a remote opening. “I couldn’t talk you in to buyin’ a TV could I Ray? You got to be the last people in Anoka without one.”

“No,” Dad said. “I don’t wanna buy one, Joe. Just rent, ‘n this one’ll do.”

“Alrighty, then,” Joe folded quickly. He’d known Dad for a lot of years. “Just thought I’d ask. You’re parked out right out front, right?”

“Ya. How much is the rental?”

“For that one,” Joe said, “We charge a dollar a day. We normally ask for a ten dollar deposit, but we won’t need that from you, Ray.”

“Thanks, Joe. So, let me see. Today’s what, the fifteenth? The liftoff’s tomorrow and they say the landing’s four days after takeoff?”

“Ya, that’s what Cronkite’s been tellin’ us,” Joe said. He paused. “You know who Walter Cronkite is, Ray?

“Yes. TV’s version of Lowell Thomas.”

“I forgot,” said Joe, as he punched the keys on the cash register, “. . . you rented a TV for the Republican convention last year.”

Dad opened his wallet to draw out some cash. “So,” he said, “maybe four, six days for the rental?”

“You don’t have to pay me nothin’ now, Ray,” said Joe, with a quick wave of his hand. “Just keep the TV for as many days as you want and pay when you return it.”

“Okay,” Dad said, returning his wallet to the safety of his back pocket. “Thanks, Joe.”

“Who knows, Ray,” the hardware man said, “you just might wanna buy the TV . . . I’ll put the rental charges against the price.”

* * *

One evening a couple of days later, our entire family gathered around the TV, with Walter Cronkite reporting Neil Armstrong’s imminent emergence from the LEM. Dad occupied the chair with the best view of the TV screen. Because the sun was down, Dad had opened most of the downstairs windows to let the stir of cooler air into the house. He had made sure the house was well insulated, not only to keep it warmer in winter but to keep it cooler in summer. It worked. Even on the hottest days, if Dad opened the windows in the evening to let in the cooler air and then closed them in the morning, the house stayed almost as cool as Moore’s house with its fancy, central air-conditioning. What Dad’s window policy meant, of course, was that he got to hear any dogs barking at night.

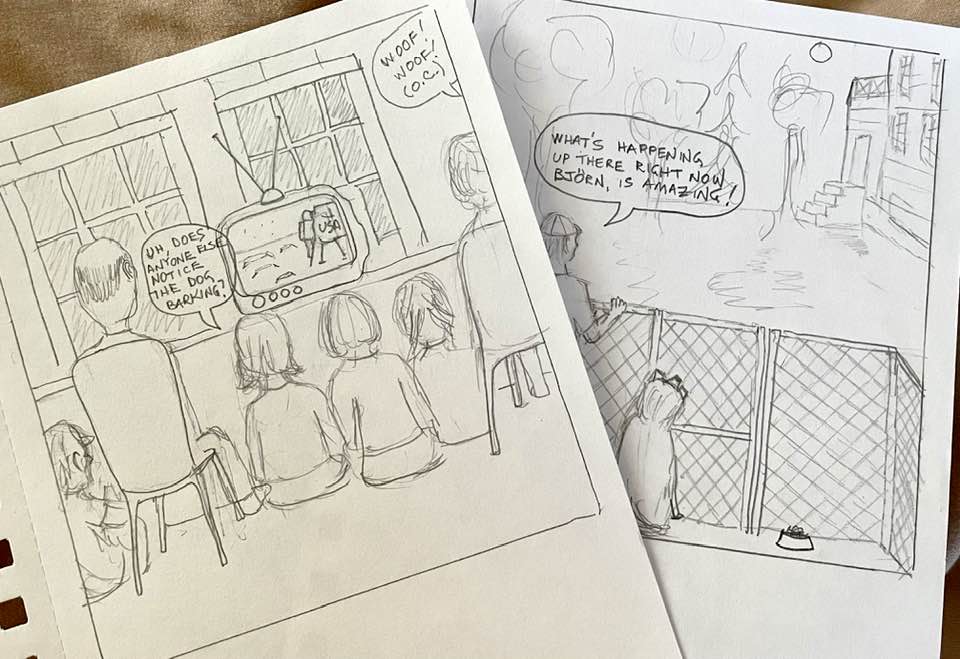

“Anyone notice Björn’s barking?” Elsa said quietly over the voice of Walter Cronkite, after Björn could be heard for awhile.

“No wonder,” Dad said under his breath and without stirring. “He’s probably hungry.”

Reflexively, I jumped up. “Mom, I’ll get his dish,” I said. Despite Dad’s apparent nonchalance, I expected a stronger response if the barking persisted.

“That’s the problem with owning a TV,” Dad said, as Walter transitioned to a reporter elsewhere on the scene at Cape Kennedy. “It’s a big distraction from responsibilities.” But Dad himself was so glued to the TV that as I left the room, I noticed no sign of agitation on his part.

A few minutes later, with Björn’s food dish in hand, I entered his kennel. As soon as the dish touched the ground, the hungry dog put his face into his food. I put my hands on the chain-link fencing and gazed up at the moon.

“Björn, big stuff goin’ on up there on the moon right now,” I said, looking down at the collie, who was eating noisily. He ignored me. “Björn!” I said, raising my voice and looking down at him. “I know you’re hungry, but I’m talkin’ to you . . .Two men are up there on the moon, Björn. I know ya can’t see ’em from here, but they’re up there.” The dog looked up at me. He panted once or twice, then closed his jaws and tilted his head slightly, quizzically, as if to ask, “And your point is . . . ?” Receiving no answer, he resumed eating his dinner.

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2023 by Eric Nilsson