NOVEMBER 11, 2023

A KING’S CASTLE – ANOKA, MN – JULY 13 TO AUGUST 2, 1967

In late July flames fanned by race riots lit up the nighttime sky over North Minneapolis, not more than 20 miles downstream from our quiet town. Before the violence was over, damages to homes and businesses would reportedly exceed $4.2 million—a lot by the dollar of those days.

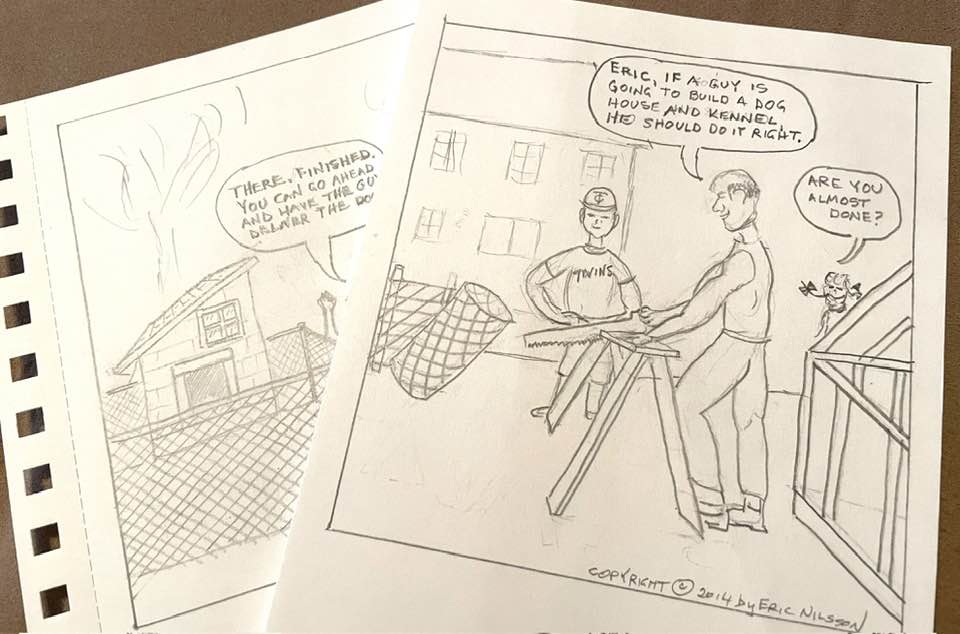

In our riverside neighborhood during that tumultuous time, the main disruption after sundown was the sound of crickets chirping in our wooded backyard. Each evening, with Bach, Mozart, Schubert, Chopin or Beethoven playing in the background I watched Dad at the dining room table, with paper, compass, ruler, pencils and eraser spread out before him. In another life he certainly would’ve been an architect, an engineer or a draftsman, or more probably, all three. He drew plans for Björn’s doghouse and kennel as if he’d won a royal commission to design the king’s castle. And like a king’s castle, as opposed to a fairy castle, Björn’s home was designed to protect, not amuse.

Dad was creative and original, a perfectionist and a pragmatist. But he didn’t go for fancy or fanciful. As much as he loved attending classical music concerts, he didn’t approve of a performer who was at all demonstrative, no matter how talented and virtuosic. He liked the pianist or violinist who could get the job done without lots of commotion.

The kennel would be located along the lot line under a telephone line, all some distance from the house and far back from the street. As Dad pointed out precisely on his skillfully drawn plans, the dog’s domain would be penned in by chain-link fencing, eight feet wide, sixteen feet long and five feet high, with a gate on the side at one end. At the other end, butting up against the outside of the kennel would be the four-by-six-foot (“outer dimemsions,” according to the plans) doghouse, standing on six cinderblocks and with an entryway accessible through an opening in the chain-link fencing. The house would have a shed roof, the lower side of which could be lifted for easier sweeping of Björn’s inner lair. Built of insulated, two-by-four stud-walls, the house would have an insulated base made out of two-by-six joists. Three-quarter-inch plywood would be used for flooring and sheathing, and all trim work would be one-by-three pine, primed, then painted white. Dad’s answer to rain and snow would be regular roofing shingles on tarpaper and on all sides as well as the roof. In the winter time, Dad explained to me, lots of fresh hay on the floor, and the fiberglass insulation in the walls, roof and floor would conserve enough of Björn’s own body heat to keep him “warm and cozy” even when temperatures dropped to 20 below. Dad’s detailed descriptions could bore you to death, but whether you paid attention or not, he never missed a thing.

Dad’s renderings of Björn’s castle and kennel were a marvel, but after they’d served their purpose they disappeared into time. My sort, sift, save and dispose operation 43 years later failed to uncover them. I don’t know what became of Dad’s drafting masterpiece of a masterwork of design.

Upon completing his plans, Dad ordered the materials. Though the plans themselves were to disappear, that was not the case with the receipts for the materials. Among all the papers Dad had archived, I would later find those receipts. He doled out close to $500—in those days, a small fortune, at least for a dog domain—to Sears and Rum River Lumber Company on the other side of town[1]. To save delivery charges, Dad hooked up the big wooden trailer and picked things up himself. I helped unload everything onto the garage floor.

Diligently each evening into August, Dad worked hard at prepping the site, installing the posts for the chain-link fence, and erecting the fence itself. With elements of the job that couldn’t possibly go wrong, he let me help. Over my young years, I’d watched Dad at work on a number of building projects at home and up at the cabin. He wielded his tools with the same grace and finesse that I’d observed my Swedish grandmother apply to tasks as mundane as stirring the ingredients for her cinnamon rolls, always made from scratch, or running the vacuum cleaner over a large carpet—after my grandfather had completed the same task minutes before, but never to her standards.

* * *

One evening while Dad was working on the doghouse and I was helping, Fred Moore appeared. Dad and I heard him before we saw him.

“Well, well, well!” Fred said to our backs. “What on God’s green earth do we have goin’ on here?”

“Oh . . . uh . . . hi, Fred!” said Dad, turning around reluctantly. As much as Dad liked Fred, I could tell that Dad knew what was coming and didn’t want to confront it.

Fred stepped up to the sawhorse on which Dad had laid a copy of the plans. Reviewing them longer than was good for any of us, Fred said, “Ya know, Ray, if I didn’t know you better, I’d say you’re buildin’ a dog house. . . and not for a yipper-snapper Chihuahua, either.”

“Well, no, not a Chihuahua,” Dad said, subconsciously shaking his head. “Definitely not a Chihuahua.”

“N-o-o-o-o. No Chico,” said Fred with a smile, referring to his family’s Chihuahua. Fred was always cheerful, even when he was being negative, which he seemed to be whenever talking dogs or politics with Dad. “But you aren’t building this Taj Mahal for yourself, are you?” Fred continued, as he closely examined the plans.” He laughed. “I mean you’re not in the doghouse yourself are you? God help you . . . I mean, God help me, ’cause with you goin’ for a dog . . . now that’s a bit much for your ol’ friend Fred Moore.”

Not knowing exactly what further to say to Fred, Dad looked at me. Not knowing any better than Dad, I shrugged at Fred. Just then, Ruth Moore saved us by calling Fred home for supper.

“See ya later, gentlemen,” said Fred, as he turned around and headed back to his house. Then came the zinger that I was sure Dad feared. “Knowing you, Ray . . .” Fred now had to shout given the distance he had gained from us, “that dog of yours won’t be barking all hours of the day and night.”

Fred’s remark prompted my recollection of Björn’s shrill bark on the steps of his owner’s house. I worried how Björn’s barking would go over with Dad and Fred now that Björn was going to be an outside dog—all the time.

* * *

Upon finishing the magnificent kennel and doghouse, Dad announced to Mother that she and Jenny were now free to arrange for Björn’s change of ownership. I don’t remember that he gave any further input or instructions or in any way ensured that Mother and daughter were prepared to manage a big, enthusiastic collie. I also can’t recall that Mother took much initiative in this regard either. What I do know is that in conversations with Mother and Jenny around that time, Dad always referred to Björn as “your” dog. Dad had done what he’d said he would do. He’d built the kennel and doghouse. Henceforth, Björn was to be Mother and Jenny’s project.

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2023 by Eric Nilsson

[1] More than 14 times the amount paid for Björn himself–$35, according to David Berg’s classified ad, which I found half a century later among the microfiche collection of vintage editions of the Minneapolis Star maintained at the Hennepin County Central Library.