DECEMBER 30, 2019 – No sooner had the full image taken shape, when disaster struck.

Down I went, as if shoved violently into the snow and . . . How on such a cold day, after such a cold week, with everything frozen hard, could I be in . . . liquid water?

This wasn’t a case where a guy breaks clean through the ice, uses a long stick, or, in my case, ski poles, spreads out his limbs and distributing his weight, crawls onto the ice at the edge of the break and proceeds to safety. This was worse. My skis broke through the crust, punched through soft snow and splashed into deep, icy slurry. My hands landed in the slush as well. Bad enough, but when the slush hardened around my feet, panic displaced my romantic sense of adventure. Despite mighty effort, I couldn’t pull my skis out of what felt like concrete, nor could I release the bindings, which were encased in fast-forming ice. Worse yet, I’d double-knotted my laces, and now they too were frozen stiff.

With all my strength I struggled but to no avail. I cast a view up and down the shoreline but saw no sign of life. McMurdo Station was half a mile west, around the bend and out of sight.

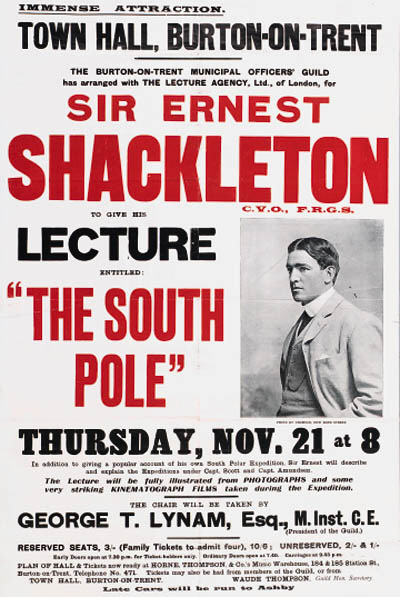

Just then, I saw a mirage—Sir Ernest Shackleton himself. What would he have done in my circumstances? One thing was certain, I told myself: he wouldn’t have lost a man. In my predicament, I called it the Shackleton Effect—When you think you’re doomed, you’re not. The Shackleton Effect released a charge of adrenalin. With a mighty pull, I broke my feet and skis free from the lake’s icy grip. I used the tip of my ski pole like an ice pick and chipped the ice away from my binding. After some effort, I managed to shed my skis.

I wasn’t yet in the clear, however. With each step toward shore, I splashed into knee-deep slush and only then realized that my left pole – the upper half still attached to my wrist – had snapped in half. The good pole I’d left behind at the place of my struggle, now four yards away. Without at least one good pole for the return to civilization, I risked losing the Shackleton Effect. I retraced my steps in the slush, retrieved the pole and made my way to shore.

With frozen mitts, an awkward stride, one pole, and a wind chill of minus 20, the trek home wasn’t easy. I’ll spare the reader further details, except to say that two hours later, I was safe and thawed, sipping a cup of hot Ovaltine inside our cabin. My wife was none the wiser—thanks to a variation of the Shackleton Effect.

I no longer questioned the story about the ice fisherman who went through the ice on White Bear Lake. Any danger is possible, when it comes to snow and ice. Older, wiser, I hope not to have to rely again on the Shackleton Effect.

(Remember to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.)

© 2019 Eric Nilsson

2 Comments

In Punta Arenas there are many reminders of Shackleton’s rescue operation ….we ‘re just huge fans and I loved your story. Totally true: adrenaline does make the seemingly impossible possible. What a story..thar was one very heard-earned mug of Ovaltine!

Thanks, Penelope (and Happy New Year, by the way!). I think the story of Shackleton’s expedition is one of the greatest tales of all time. I read it while angling for a promotion as division head at Wells Fargo. At the opening of my final interview with the ultimate decision-maker, I presented a copy of the book and suggested that he make it required reading of all his direct reports. I told him it was a case study in enlightened leadership–identifying the strengths of every single person in the group, then allowing each person to play on his (her) strengths for the benefit of the group. He thumbed through it while registering a wholly incurious, unimpressed, uninterested countenance–and handed it back. That signaled that my candidacy was in jeopardy. Later, when a peer of mine got the job (and who soon thereafter turned around and summarily fired me!), I asked the big-wig why I hadn’t gotten the job (I’d lobbied hard in ways that I thought were constructive–building support within the organization; advancing ideas about motivating people to work their strengths for the long-term profitability of everyone concerned). His answer: “You have to understand that working in a large corporation is like working in the army. You follow orders. You don’t question authority.” I was glad to leave.

On another level, Shackleton’s travails highlighted the tragedy that was playing out back in Europe. When the intrepid leader and the other men who’d found their way to Elephant Island and stumbled into the Norwegian whaling station, they asked, “Who won the war?” The answer, of course: “It’s still going on.” One or two of the expedition members who, upon their return to England, went off to war were killed. Killed!–after having survived impossible odds down in the Antarctic. How entirely tragic!!

On a biz trip to NYC soon after the book came out, I went to the photographic expedition at the Museum of Natural History. The plates were AMAZING. Also on display was the James Cairn–the lifeboat that Shackleton and others had used to navigate across the Drake Passage. The boat was set up in a room surrounded by circular panels on which a video of heavy seas and fast moving clouds were projected. On a stationary stand was a sextant with which visitors could try their skill (or lack thereof) at shooting the sun. It was damned near impossible–from a stationary platform! As I recall from the book, the navigator was able to secure only four or five shots over the course of the entire +800-mile voyage!!!!!

Later, I watched a documentary about some modern-day adventurers who re-enacted that voyage, including the trek across Elephant Island. They hurtled themselves the same slope that Shackleton and crew had descended–butts on coiled ropes! Their estimated velocity: 60 MPH.

On what other planet, in what other galaxy, in what other universe do such things occur as what happens here on earth?!

Again, Happy New Year, and thanks for reading my posts. If just a handful of people sign in every day, I find the motivation to maintain this daily, personally fulfilling discipline.

All the best,

Eric

P.S. I think you live in a fascinating country, and I thoroughly enjoy all your FB posts of scenery/about life down there.

Comments are closed.