JANUARY 10, 2024 – During my sheltered life leading up to the sales job, I’d had little interaction with Black America. What encounters I did have with Blacks were either superficial or not at all instructive.

At the superficial end, when I was in kindergarten our family took a road trip to Florida via the Great River Road following the Mississippi to New Orleans, then across the Deep South. From the comfort of Dad’s Super Buick, we saw rural Blacks trundling along the road or across a nearby field. In constant disbelief of the shabby condition of their hovels, Dad was forever pointing them out to us. “They can get by with a lot less sturdy construction down here,” he said, offering an explanation, “since they don’t have to contend with 10 below zero weather.” Even as a five-year old kid, I wondered why the people we saw would choose to live in a shack just because “they could get by with a lot less.”

Because we saw so many reruns of Dad’s 8mm movies of the trip, I’ll never forget the scene in some part of the South where he stopped to film Black kids emerging from a rural schoolhouse. When Dad trained his Bell & Howell camera on a young teenager wearing a yellow slicker and a cap, the kid noticed and took his cap off until Dad stopped filming, whereupon the cap was returned to its perch. Dad was amused by the kid’s politeness. I was impressed. I didn’t know anyone back home who would know to do that.

At Sterling School I knew the two Black kids out of 100 students and at Interlochen, the seven or so out of 450. None was from an underprivileged background. As I recall the Interlochen contingent, in fact, most came from decidedly upper middle class families. I remember well the friendly argument that broke out at the dinner table one evening between two friends of mine, one Jewish, the other Black, each the son of a surgeon. The crazy debate was over whose father was wealthier, except it didn’t ensue the way you’d assume. Each kid took the position that the other guy’s father was the wealthier. “Your father is definitely richer than mine,” the Black kid said to my Jewish friend, whose father was a prominent plastic surgeon in Atlanta. – “No, definitely not,” my Jewish friend said in retort. “Your dad has to be much, much richer.” Our Black friend’s father was the head of surgery at some major hospital in a big Midwestern city (Chicago? Detroit? I can’t remember). The argument dragged on until the rest of us wearied of it and left to go practice our respective musical instrument.

At Bowdoin the handful of Black students were more representative of the majority of Blacks in this country—meaning less privileged than the majority of whites. They tended to self-segregate from the rest of the student body—or least that was the prejudicial notion that I shared with most white students. Occasionally, however, it occurred to me that maybe their “self-segregation” was more a matter of “societal-segregation,” and that we white students were as much or more to blame for it than the Blacks were. But I was too naive, too immature, too ignorant, too lacking in self-confidence to do much about it. I assuaged my naive conscience by smiling and saying, “Hi” to Black students “just as I would to any white student.”

* * *

As my daily door-knocking got closer to the Buffalo city line, I began to face overt racial prejudice that shocked my protected, privileged, provincial sensibilities. I remember well the very first encounter.

I was in the process of wrapping up a conversation with an older middle-age couple who were doing some yardwork in front of their house. They’d been cordial but uninterested in buying a book—the one-volume encyclopedia or medical encyclopedia; I hadn’t bothered with Bible Stories. When I asked the standard question, “The folks next door . . . do they have kids?” I unwittingly lit a fuse.

“You can pass them by,” said the man.

“Why?”

“They’re block-busters,” said the woman, “and we’re not happy with them.”

“What are ‘block-busters’?” I asked.

“Block-busters are n[—-]s who try to look respectable,” said the man. “You know, dress nice, drive a nice car, and so on, but they’re really up to no good. They buy a house in an all-white neighborhood, see, but their goal is to force whites who’ve lived there forever to move. And it starts to work, because who wants to live next to a n[—-] family? So people start moving out and n[—-]s start moving in, and before you know it, the whole block and eventually the whole neighborhood flips from white to n[—-]. The first family—in our case, right next door here—they’re the ones designated to start the dominoes dropping. That’s why they’re called ‘block-busters.’”

I didn’t know what to say, so I just grunted.

“Yeah, and you look around Buffalo,” said the woman. “Wherever blockbusters move in, before you know it, the whole neighborhood goes down the slide.”

“Do you have plans to move?” I asked.

“We’re thinkin’ about it,” said the man. “Got to before everyone else moves out and our house drops in value. Then what are we supposed to do, sell real cheap to a n[—] family? Not on your life.”

Eventually I moved on—to the “blockbusters’” house, but no one was home.

Another incident that etched itself into my memory also involved a couple out in their front yard. They’d been playing with their kids until I came along to interrupt their fun and games—or actually to participate by retrieving for them a stray ball that had bounced in front of me and across the street. I maneuvered the circumstances into a setup for my pitch.

The folks weren’t interested, and in fairness to the kids, not to mention my meeting the day’s sales quota, I soon decided to ask about “the folks next door.”

“Yeah, they have kids,” said the man, “but you’d be wasting your time.”

I was amused by the irony of his assessment, since technically he’d wasted my time. “Why do you say that?” I asked.

“They’re Blacks. They wouldn’t be interested in education or books or anything like that.”

Of course, I took the risk that I’d be “wasting my time” by continuing next door. As it turned out, the people were interested in education and books—enough to buy the one-volume encyclopedia.

* * *

Day by day I worked farther into Buffalo until I was a half hour from the Mikolons’ Grand Hilton—by car not walking. I’d never in my life hitch-hiked, but the sales job had boosted my chutzpah in a number of ways. Moreover, the absence of viable alternatives motivated me to try things I’d never before contemplated. I was pleasantly surprised by how easy it was to hitch a ride, and soon it was my exclusive method of getting to and from my territory each day.

Toward the end of June I was deep into a large part of town that as far as I could tell was the exclusive domain of Black families. The houses were of the early 1900s, and for the most part, they were reasonably well maintained. For the next couple of weeks, I experienced life in the very small minority. I was amazed by how accepted I was, and it took little imagination to contrast how I, the lone white guy, was treated to how I knew a lone Black guy the same age would be treated in my neighborhood at home: with caution, suspicion, wariness, even outright fear.

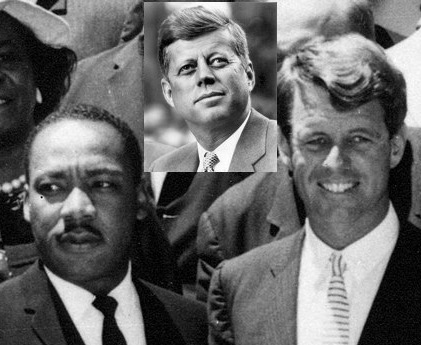

I was welcomed into nearly every house I called on where someone was home, and my sales numbers—for all three books—skyrocketed. The highlight of the experience, however, was my long, involved conversations with people. In every single house I saw displayed in a prominent place, a framed portrait of one of three people; Martin Luther King, Jr., Bobby Kennedy, or JFK. Around suppertime I was inevitably invited to join folks for dinner. At other times, people would insist that I join them on the front veranda to share lemonade and shoot the breeze.

On several occasions I encountered Vietnam War veterans, who had much to say politically and otherwise—through music and poetry. I wound up talking for nearly two hours with one veteran who’d been fairly radicalized by his experience. When I realized how late the hour had grown and how the Mikolons would no doubt begin to worry about me, I told my host that I really had to be going.

“How far you got to go?” he asked, as he opened another beer.

“A long way from here,” I said. “Cheektowaga . . . almost to the airport.”

“Damn!” he said. “Why didn’t you say som’n?”

“The people I’m staying with have probably launched a search party for me.”

“Tell you what,” the veteran said, after taking a big swig of Bud. “You call ’em. Then jump in my car, and I’ll have you there in no time.”

The guy’s charity toward me was more evidence, if I needed any, that angels walk this earth.

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2024 by Eric Nilsson

4 Comments

Very nice story. A good experience. Thanks.

Glad you liked this installment, Alan. The exposure was good for an insulated white guy like me.

Great piece, Eric.

Thanks, Davis. It was quite an unexpected benefit of the experience.

Comments are closed.