JANUARY 14, 2024 – Despite the fear of failure that always accompanied me—sometimes out of sight in the shadows, sometimes writ large upon the door slammed in rejection—now and again I surprised myself. Three weeks into the sales job, I hit a gold vein in an otherwise desultory sales territory. I felt as though I’d hit a slot machine that the house had mis-rigged. By the end of the week, my numbers were exceptional. At the Sunday regional sales meeting I was among the top 10 “honor roll” salesmen of the week called to the front for special recognition and applause. I was eighth, and no one could’ve been more shocked than I. That evening I called Fred Moore—my designated booster back home—with the good news, and he was genuinely pleased with my report.

If this surprising performance put me in a positive frame of mind, it didn’t last long. The next day, I remember, was one of my toughest, despite blue skies and sunshine. After having stood (improbably) on the summit, I was now starting all over again—at sea level. How could I possibly repeat my aberrational performance? In fact, it foreshadowed my future days as a lawyer fixated on the accumulation of monthly billable hours: with the turn of each month I had to start all over again. Likewise, in escaping the grind of billable hours by going to work for a bank, I wound up in a different sort of slog: as head of a profit center, no matter how much over plan my group performed in any given reporting period, my marching orders were to do better in the next. We always started the new month, quarter or year at zero, and the climb was inevitably steeper as time progressed. Such is the reality of the business world.

My spirits were so down on that Monday following my best week in Buffalo, I went a couple of hours without making a single call. I just walked; wandered from residential neighborhoods into a retail business district. I felt a surge of homesickness and a need to talk to my dad. I knew he’d understand and empathize. He’d once told me about his own sporadic sales jobs before he’d gotten “a real job,” and how “cold-call selling just wasn’t for him.” Consumed by my despair I searched for a pay phone, exchanged a couple of dollar-bills for coins, and called Dad at his office.

As luck would have it he picked up his phone. His voice was like a life buoy with the phone cable inside the booth serving as a life-line. I told him my woes. Psychologically I felt as if I were committing high treason against Southwestern. Was the call grounds for being fired? For being labeled a loser? For being shot as a traitor to the whole regime of PMA? I expressed some of this to Dad, and he assured me that none of it was true. He empathized thoughtfully and convincingly, thus restoring my equilibrium. In effect he allowed me to “have it both ways.” On the one hand he conveyed absolute faith in me and gave me more effective encouragement than the company’s propaganda ever could. At the same time, however, he said it was perfectly okay to quit and return home. He and Mother would welcome me with open arms, he assured me, “no matter what that company thought” of me. It was a calculated tack on his part, a balanced approach with unqualified support for whatever decision I chose to make. Its immediate effect was to turn me back to the residential neighborhoods to finish the day on a . . . positive note.

Dad’s support wasn’t my only source of encouragement—or license to quit.

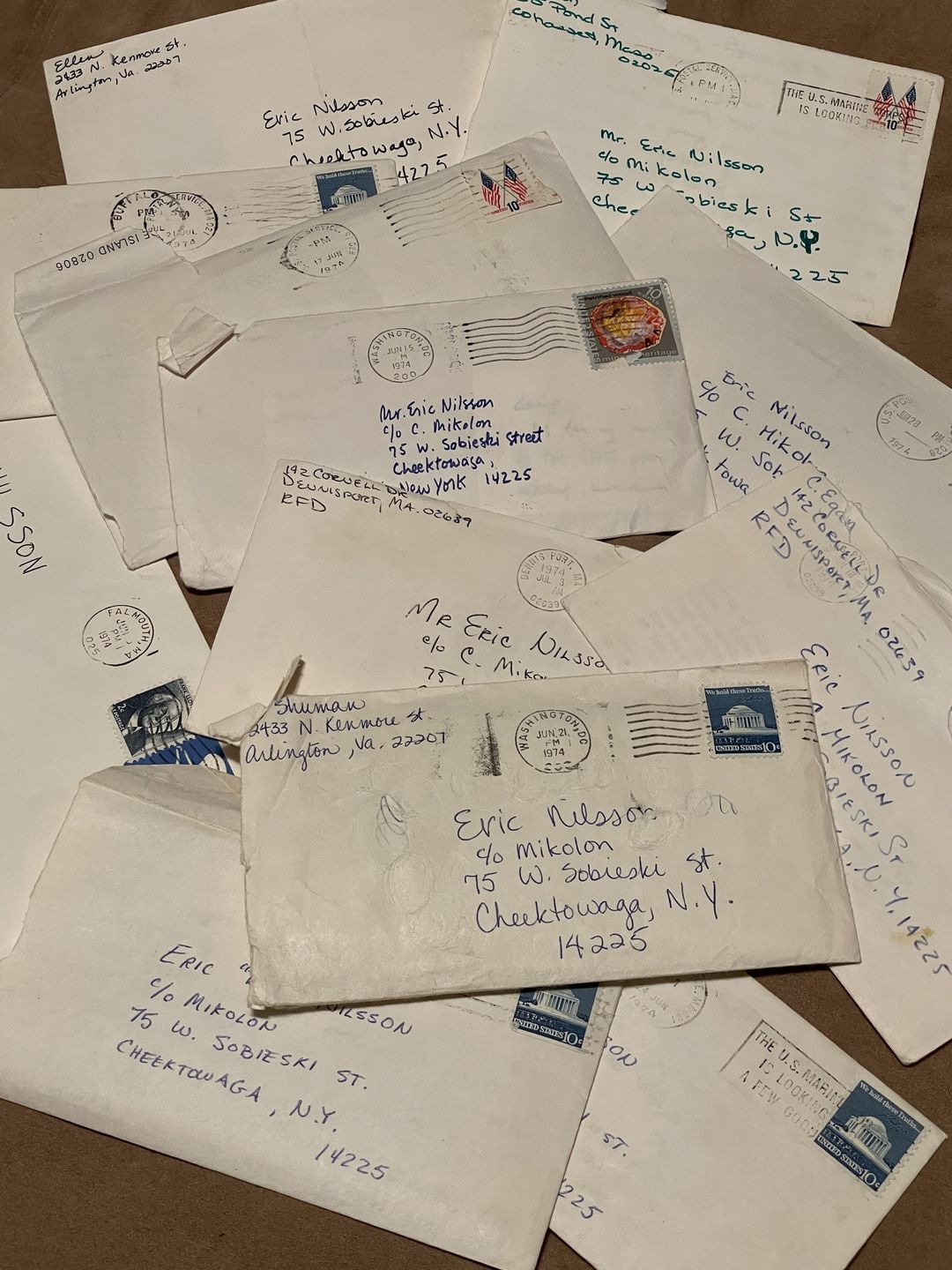

Recently, I uncovered a rich cache of letters from college friends addressed to me “C/o C. Mikolon,” at my hosts’ “Grand Hilton.” For each of the letters I received was a letter I’d penned. Judging by the former I could accurately guess the contents of the latter. The correspondence reflected the ups and downs of door-to-door sales. (What struck me more than anything as I read the collection of letters again for the first time in nearly 50 years was that back then we actually wrote by hand long, legible, intelligible letters. As one of my friends captured the essence of letter-writing, “One thing about letters is that the author has absolute control over the direction—and without interruption. It must be a weird feeling to write a novel; to create people, events, and everything; even to be able to change the past. Wow!”)

One good letter example was penned by a “Cynde,” a student from Wellesley College who’d spent her junior year at Bowdoin and on whom I’d had a sometime crush.

Well, Eric, I don’t know how to react to your last letter. You seem to be getting “the experience” you wanted to get. I just hope you aren’t paying too high a price. I encourage you to stick it out as long as you can, but at the same time, to keep in mind that this “experience” won’t be any good if your sanity gives way.

My close friend Jeff Oppenheim—nine years later best man at my wedding—wrote regularly:

Dear Eric, June 14, 1974

Your letter was super reading material . . . Your job sounds incredible. It is tough to tell whether you love selling or whether you are just tolerating it while enjoying talking with people . . .

Dear Eric, June 23, 1974

Thanks for your lengthy letter. Despite your near breakdown it sounds as if you are a financial success. Remember, we figured if you cleared $2,000 at the end of the summer you could consider the summer economically successful.

Dear Eric, July 6, 1974

Got your letter on Saturday and though I would write as soon as I could since your situation sounds (is) unpleasant. I wonder whether you were allowed a leave of absence. If that company is at all smart they will not let you go. You are no doubt an asset to them. An honor roll salesman should not be discarded. There is not much I can tell you, since I am not in your predicament. I think you understand how valuable this experience is if you truly want to go into politics. . . Maybe you should pretend that you are selling yourself rather than the books. Pretend you are campaigning for the Senate, and the purchase of one book represents one vote. Please keep me posted on your situation!

Another batch of letters came from my Bowdoin roommate Tom—the one who’d had to pack up for the library on that occasion when Mike had come to campus to pitch me on “a fantastic opportunity.”

Dear Eric,

How are the “Bible Stories that Live” selling? It sounds to me from you latest postcard at though you are really getting something out of your job. It must be tough going all the way. The attitude that you display through your writing is probably the best I can imagine. If you had to take work seriously all the time you would have a good chance of going crazy in a few weeks. Even as it is, you have have a few good days sprinkled here and there ($125 in two days ain’t bad). You have my hearty congratulations on surviving up til now and my sympathy in your future dealings.

Dear Eric, June 28, 1974

I’ll tell you, I’d put you on the company honor roll for just sticking with your job. You really make it sound like a burden to your health. I’m told that my grandfather Griffin once tried working as a salesman (probably for the same company as you) and had such poor luck that he wrote home for his camera and had better luck as a travelling photographer.

Yet more letters came from my good friends Ellen and her boyfriend Peter. In a letter in early June, Ellen reacted harshly to the company commandment that the first call of the day was to be made by 8:00:

Dear Eric –

You’re absolutely right. If anyone (especially a salesman) knocked on my door at 8 AM I’d be furious, and I certainly wouldn’t buy the product. My eyes wouldn’t even be open. It makes much more sense to start at 9 or so every day, and you should tell that to the company. I bet they actually lose money by making you fellas get out of bed so early in the morning.

Eric, I must say, last week Peter and I were both awfully worried about you. You’ve really pulled through with a gold star! I’m sure much of your job is having the proper mental attitude; not necessarily what the company wants you to have either. It takes time in a job like that to find the proper balance between the salesman side of you and personal side. A good salesman doesn’t just push his products. He must use tact and reserve as well. I think you’ve probably found the best way for yourself to go about selling. – Let me make a confession. I could never do what you’re doing. I’m scared just to call up someone on the phone that I don’t know. Or sometimes even someone that I do know. Yikes[1].

A week later Peter sent me a letter filled with encouragement—along with a less than positive view of Buffalo:

Dear Eric – Saturday Morning 6/15

Thank God you sound so cheerful!! To say the truth, I had many doubts and reservations about your summer endeavor, but they were all jettisoned as soon as I perceived the tone of your writing. Eric, you’ve embarked on a valuable adventure which if taken as a mixture of serious experience and weird fun could be the best summer of your life. Don’t take it too seriously—especially when beset in Buffalo, NY (I’ve been there twice), which is not only the pit if the East but of N. America as well. Wow, that can be a depressing place—it’s cloudy a lot and dirty all the time. However, there is one distinct advantage—the people on the whole are dumb (the smart ones figure out a way of escaping) and this no doubt will increase your success with those dubious Southwestern products you so smoothy ram down their throats.

At the time of receipt, these letters were life-savers; verbal care packages. Southwestern would’ve condemned them as subterfuge. In the end I they were but again . . . I’m getting ahead of myself. The letters were interesting from another perspective: they described interesting highlights and low points of my friends’ summer jobs. Our ivory tower perspectives were being stretched by life out in the “real world.”

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2024 by Eric Nilsson

[1] An art history major at Bowdoin, after graduate school, Ellen went on to a highly distinguished career as an institutional investor for endowments and foundations, including Yale University Investments and the Carnegie Corporation, in which career, ironically, she doubtless called thousands of “people that [she]didn’t know and even that [she] did know.” Her father was a legislative aide to maverick Senators William Proxmire and Paul Douglas.