JANUARY 5, 2024 – The week of sales training was about 25% actual sales training and 75% attitude adjustment. The sales part was intense, well-organized, and highly disciplined. It had to be, since the only way Southwestern sold product was by a bunch of callow college students pounding the pavement—and pounding doors along the way. If we didn’t sell, the company would have no revenue. But the company also understood that our battles wouldn’t be against an inhospitable world of door-slammers. At least three-forths of our challenge would be our own despair and discouragement. Conversely, that same portion of our success depended on a positive attitude in the field.

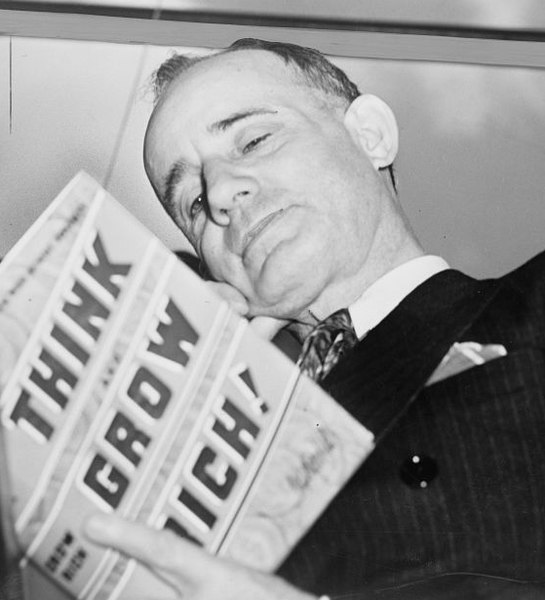

Every recruit received a copy of Og Mandino’s 1968, The Greatest Salesman in the World and Napoleon Hill’s 1937 classic, Think and Grow Rich. There were other materials we were expected to digest, as well, but in every case it came down to “PMA”: “positive mental attitude,” a phrase coined by Hill. It was my friend Mike, however, who connected PMA back to Interlochen.

Many things on campus were called “Stone,” and not only because they happened to be made of mortar and stone. All visitors at Interlochen checked in at the “Stone Center,” with its warm, casual lounge and welcoming reception desk, in contrast to its cold cinderblock exterior. The place doubled as a small hotel, and on the other side of the reception area was the dining hall where we gathered for all of our meals.

Orchestra rehearsals and concerts took place in the “Jessie V. Stone” building, which we called “JVS” for short.

And we all knew that the school’s biggest benefactor was W. Clement Stone, based in Chicago. Periodically, Mr. Stone and his wife Jessie (V.) would make an appearance. The dapper looking man with the pencil moustache was a friend of President Nixon and purportedly had almost as much money as a Rockefeller. We were told that he’d made his many millions selling newspapers, then insurance policies. I hadn’t thought much about W. Clement Stone beyond the established fact that he was rich and gave loads of dough to our fine school.

When I landed in the thick of Southwestern’s “PMA” training in Nashville, however, Mike linked Stone—and thus Interlochen—to the doctrine of positive mental attitude. W. Clement Stone was a close associate of Napoleon Hill. The fact that Mike had strong family ties to Chicago, where Stone was better known than in Minnesota, probably heightened Mike’s own unrelenting spectacular embrace of PMA.

* * *

By way of background, if I was generally happy and well-adjusted, I’d also inherited a proclivity for grouchiness and negativity with an occasional dash of depression, especially when faced with the prospect of spending a brilliantly gorgeous fall day—all of it—down at the Gilombardo School of Music, first in solfège class, followed by music theory, then a private lesson, then chamber orchestra rehearsal. When things didn’t go exactly my way, I could out-pout anyone in the family.

If my mother was a joiner and a happy camper, who interacted respectfully with people of all stations in life, my dad saw the world as a place with a few really smart, competent people with excellent tastes, standards, and judgment and a whole lot of people who possessed none of these attributes. Most Democratic politicians, it seemed, were from the larger lot, and when it came to missteps or shortcomings in the political and governmental realms, Dad would go negative faster than you could say, “Hubert Humphrey.”

Dad was by nature a critical thinker, just as Mother was an analytical one, the difference being that Dad readily saw how things might go wrong, while Mother could just as quickly figure out a way to turn wrong things right. The best example of this was when I turned my hard-earned pay as Moore’s summer “groundskeeper” loose on a new Sears Roebuck sailboat called a “Fleetwind.” When Dad first saw the sail with a big “F” emblazoned on it, he said, “What’s the F for—failure?” Mother, on the other hand, happily bought a “stock certificate” I made, issued by “Fleetwind Incorporated,” for which investment she paid me $100. In lieu of cash dividends I promised her “free rides” up at the lake.

In any event, as a result of my parents’ somewhat opposing influences, by the time I found myself in “PMA” training in Nashville the summer I’d turn 20, I had a well-practiced dual disposition of negativity and positivity. As a consequence, I was at once skeptical of “PMA” and susceptible to it.

What grated on me were the regular times when one presenter or another would direct us all to jump to our feet and scream some inane line such as . . . “Act enthusiastic, you become enthusiastic!”—Mike’s favorite. It’s not as though I never said dumb stuff. I was a master at it. But with one major exception, I’d never been part of a large crowd yelling dumb stuff.

My freshman year of high school was at Sterling School in Vermont with an entire student body of only 100. There were no crowds cheering our ski team because most of us were on the ski team. For the rest of high school I attended Interlochen Arts Academy—450 students (four grades)—which didn’t even have sports teams (beyond P.E. and pick-up games). If audiences shouted their applause, they never yelled anything as dumb as, say, “Bite their eyes!”

Screaming “Bite their eyes!” was a chant initiated by an esteemed professor of economics at a hockey game at Bowdoin, a liberal arts college with only 1,250 students. Home hockey games drew a large percentage of those 1,250—I being among them the game-goers. Well plied with beer, I tried to out-yell the professor and sometimes succeeded.

But now in Nashville I was squeezed into a crowded windowless movie theater and surrounded by every frat boy, it seemed, from the top 10 biggest sports and frat universities of the Great American South. The only thing missing was the beer. The place went nuts nuts whenever the presenter pumped his arms to signal that we needed to shout the designated positive-mental-attitude-slogan ever louder. I imagined that the hordes around me were, in turn, imagining that they were at a bowl game featuring their beloved (and favored) Crimson Tide or Seminoles.

I struggled. Bowdoin had team sports and fraternities too, but their scale was nothing compared to that of the mega schools. If not every Bowdoin student was an “intellectual,” all of us studied hard to meet the prevailing standards across a broad liberal arts curriculum. Most of my fellow recruits in Nashville, I learned, came from very different academic molds from mine. Many seemed to be double majors—business and shouting “Rah, rah, rah!” at the tops of their lungs.

The more we were directed to yell, “Rah, rah, rah!” the more negative reaction I had to Southwestern’s attempt to indoctrinate me with a positive attitude. If Mike was worried about me, he didn’t say. More likely, he didn’t really notice. He was too hellbent on shouting “Rah, rah, rah!” Where had he learned to do that? Not Interlochen—but then I reminded myself. He was a business major at the University of Illinois – Urbana-Champaign; not exactly the South but a school that at the time was almost 30 times the size of Bowdoin.

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2024 by Eric Nilsson