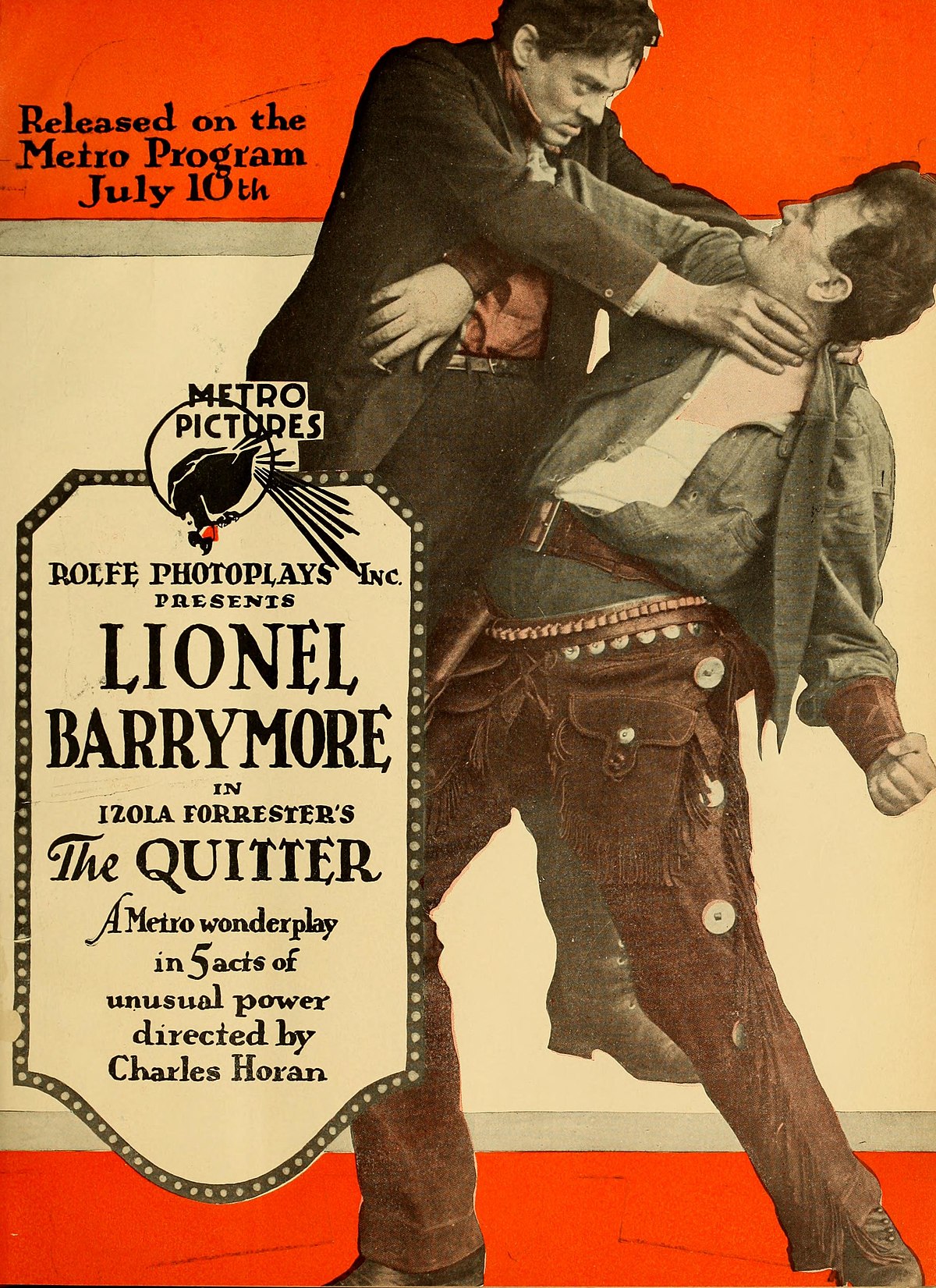

JANUARY 17, 2024 – A key to Southwestern’s business model was making it difficult for any salesman to quit.

In the first place, the only way you got paid was to work all the way to the end of the summer. During the third week of August the company would ship books to a centralized drop point in your region. You’d then have to arrange to pick up the books that you’d sold and deliver them to customers. You were supposed to collect half the total cost when you closed on a sale. The other half you had to collect at the time you delivered the book. Only after all collections were accounted for would you see your commission check. If you quit before the bitter end, someone else would inherit your customers and half your commissions, and you’d be at the mercy of your inheritor’s luck, motivation, and competence, and in any event, from a timing standpoint, as a quitter and a loser, you’d be last in line to receive your share of commissions. The worst part of it was that to be eligible to collect your crumbs, you had to quit in person in Nashville.

Which gets to the other part of the company’s strategy: the psychological one. As I’ve mentioned in previous chapters, Southwestern pummeled us with a two-pronged doctrine: 1. Positive Mental Attitude, expressed as “Act enthusiastic, you become enthusiastic”; and 2. If you even think about quitting, you’re a loser, and if you actually quit, you’re a shameless loser, to be forever marked as such as you go about the rest of your miserable life.

My small group of friends—Rodger, Robbi, a guy named Greg (who had another brother who was a sales manager)—had wanted desperately to quit, they were too chicken. I didn’t blame them.

By the end of June we’d formed our own little rebel group, and given our common negative disposition toward the job and the company, we were living proof of what would happen inevitably if you didn’t say “Act enthusiastic, you become enthusiastic” out loud at least 500 times a day.

The inevitable finally hit me: the overwhelming desire to quit. The process, however, turned out to be the most challenging aspect of the whole experience. I documented it well in another letter to my friend “Cynde”—first in a draft, which again, was among the letters I’d saved from that summer of ’74.

“I finally decided to split from the pit of North America,” I wrote . . .

. . . Before I relate the events surrounding my escape, I [should note] that I left Buffalo before my sanity left me. My last week was my best week.

On Wednesday evening I phoned a fellow salesman and one of the few whom I did not detest.

“Hello there, Robbi,” I said when he answered his host’s phone. “How ya doin’?”

“Hell, this job sucks,” he said. I laughed and Robbi joined in.

“Are you and Greg going to drive over tonight?” I said [Greg was his roommate and also a very good friend of mine.] “It’s nearly 11 and I don’t want to be up too late.”

Each Wednesday Greg, Robbi, and another salesman, Rodger, would drive over to Cheektowaga. We’d go to this ice cream palace where one could get a cyclopean ice cream cone—any flavor for only 40 cents. It was our one opportunity during the week to exchange tales and laugh together.

“Sorry, Eric, but we won’t be over tonight or any Wednesday night from now on. Greg split town yesterday morning,” Robbi said with a tone of resignation.

“He what?” I said.

“That’s right. Monday night he stayed up really late. He was in the next room with the door shut and the lights on. I thought he was reading, but as it turned out he was makin’ all sorts of phone calls to his brother the sales manager, his parents, and a whole mess of other people. Then he woke me up and said he was quittin’.”

“Damn!” I said. “He could’ve at least told me too,” I said.

“Why?” asked Robbi.

“’Cause I’m thinkin’ of doing the same thing. We could’ve gone to Nashville together.” (The company requires you to return to Nashville in order to straighten out your account.)

As Robbi and I conversed for another half hour I became more convinced that what I wanted was out. To hell with the company. I wanted out!!! On Friday night I called Keith, my sales manager. Cynde, I was nervous as hell. The company makes you feel like a river rat if you quit. My hands were sweating like mad as I dialed the number. I watched the dial as it spun around.

No other number seemed so long. I knew what to expect, and I was scared as hell. ‘Click’—the connection was complete. I listened for the ring, but . . . b-z-z . . . b-z-z . . b-z-z . . . the line was busy. I dropped the receiver back in the cradle and sighed with uneasy relief. Five minutes later: the same thing. By the fifth try I got through. The tension was gone. I was cool and collected.

“I’m sorry to inform you of my resignation.” The words seared my own ears and stunned Keith.

“Oh yeah?” he said “Well, we can discuss it at the Sunday meeting. Meanwhile, get out there and sell!”

Now I knew the guy was a real con-artist and would try his sales tricks on me . . . hoping to change my mind. I refused to acquiesce. “Maybe you didn’t understand me,” I said. “I’m quitting.”

“Okay,” he said. “Call Joe [the regional manager of the company] tomorrow morning.” – ‘Click.’

Keith’s lack of argument or any further pushback surprised me. Perhaps he understood more than I’ had assumed[1].

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2024 by Eric Nilsson

[1] Much later I learned from Mike that some weeks after I’d quit, Keith’s younger brother—whom Keith had recruited as a summer salesman—had been struck and killed while riding a bicycle to his sales territory. When I heard this, I gave Keith a giant pass. I couldn’t imagine the guilt-ridden grief he must’ve experienced. I confess to not having made the effort to track him down to express my condolences.