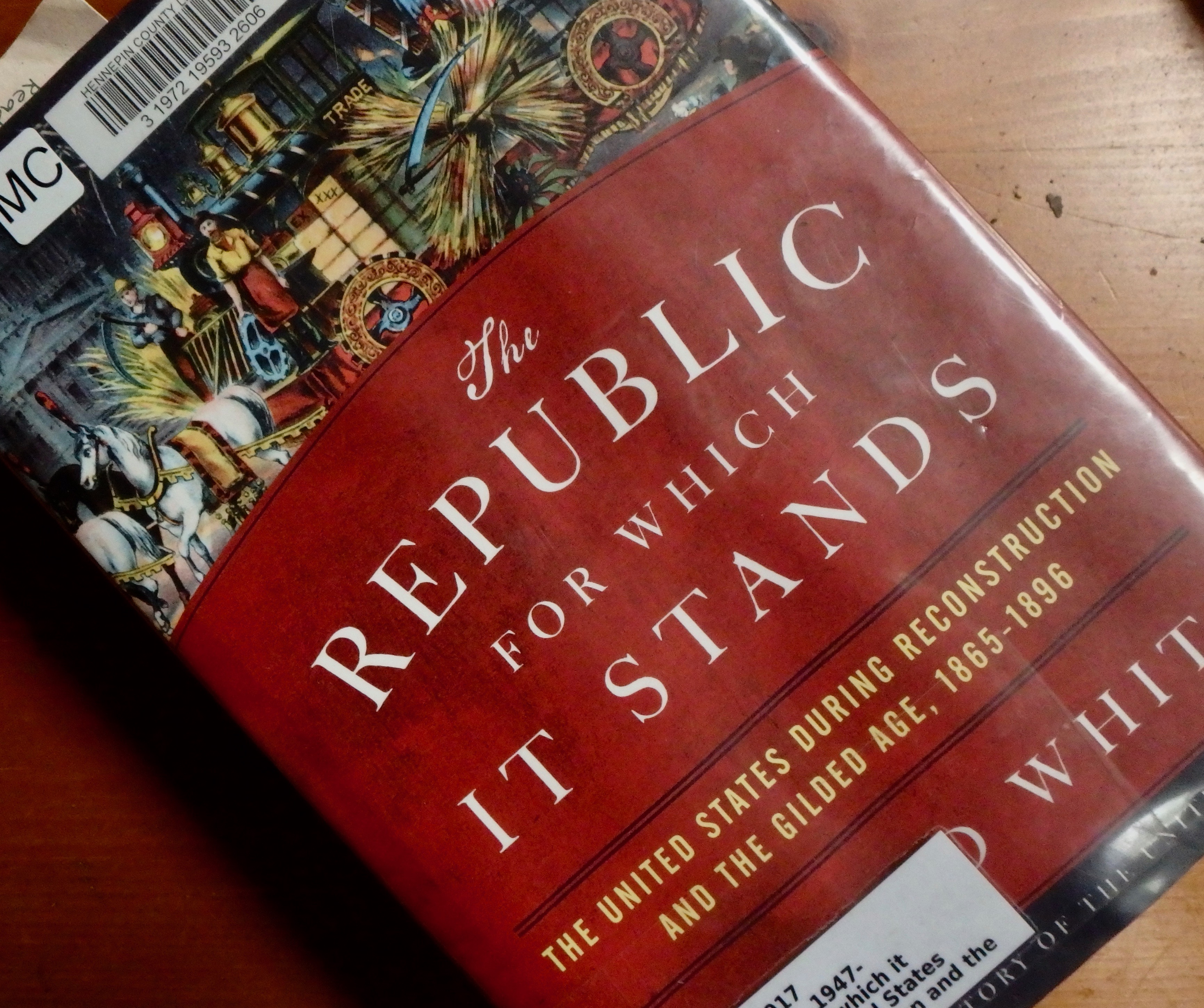

OCTOBER 2, 2019 – I am well into a nearly 900-page work of scholarship and analysis by historian Richard White entitled The Republic for which it Stands. The book is not for the faint of heart (or short of attention). It provides a detailed account of Reconstruction and the Gilded Age, and for me, anyway, fills in much of the “flyover” period of my prior study of American history.

Years ago as an undergraduate, I read and studied some about the aftermath of the Civil War—formulation and passage of the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments to the Constitution; some about Andrew Johnson, Lincoln’s immediate successor as president; some regarding scalawags and carpetbaggers, and, of course, a bit about The Klan.

I’d read even less about “Indian policy” in the West. What I’d know about that part of North American genocide was limited to a book now and again since college.

I’d known even less of what Mark Twain had dubbed sarcastically, “the Gilded Age”—a time when the country seemed to flash like gold but underneath was fueled by corrosive toxins of epic corruption (e.g. the two-term presidency of General Ulysses S. Grant).

But White does more than pull the scab off America’s past and conduct a surgical probe of the wounds that still fester below the epidermis. He explains how powerful and pervasive concepts such as “home,” “competence,” “free labor,” and “laissez-faire” (as well as the latter’s many exceptions) influenced our course through time.

Before White’s work, all that I knew and could recall about America from 1865 to 1896, I could fit on one page, in large print and double-spaced. Thanks to his research, synthesis, and excellent writing, I now understand much better the social, political and economic wheels that drove our republic from the bloodiest conflict in its history down a bumpy and uncertain road toward the 20th century.

Reading such a detailed study of the past is not mere “entertainment” in the manner of attending a horror movie. Nor is reading this history an empty psychological exercise in self-flagellation. It is essential to an understanding of the influences and behaviors that determined the course of events. Only by that understanding can we begin to plot our way into a better future.

No period of humanity operates from a clean slate. By the same token, no generation is condemned to live indefinitely captive in the prison of its ancestors. If first the walls, the doors, the locks, the upper windows of our collective confinement are examined, the better our chances of escape.

And this to know as well: however cold, dark, and dank the dungeons of our forebears, by tooth and nail, individuals, small groups of people, and whole movements among them found their way out of the coldest, darkest, dankest corners. In so doing, our ancestors showed us endurance, determination, and resilience. From those qualities may we draw hope and inspiration so that our own heirs, in turn, will see in us—endurance, determination, and resilience.

(Remember to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.)

© 2019 Eric Nilsson