MARCH 9, 2025 – This evening I finished devouring a most fascinating book, The Pearl by Douglas Smith. It was recommended enthusiastically by Theofanis the Great—better known as Professor Stavrou, le tour de force of Russian history at the University of Minnesota College of Liberal Arts.

In his introductory lecture a month ago, he assigned a AAA rating to Mr. Smith, who was born in the year of the Cuban Missile Crisis. Coincidentally, Smith grew up in Minnesota before attending UVM (University of Vermont) and obtaining his PhD at UCLA in Russian History. (He now lives in Seattle.) Smith has spent his entire career immersed in Russian and Soviet studies and related activities, including serving as President Reagan’s interpreter, and traveling widely and frequently to Russia and the USSR. He’s written and lectured extensively about Russia, and I’m now salivating at the prospect of reading his next five books on my book list.

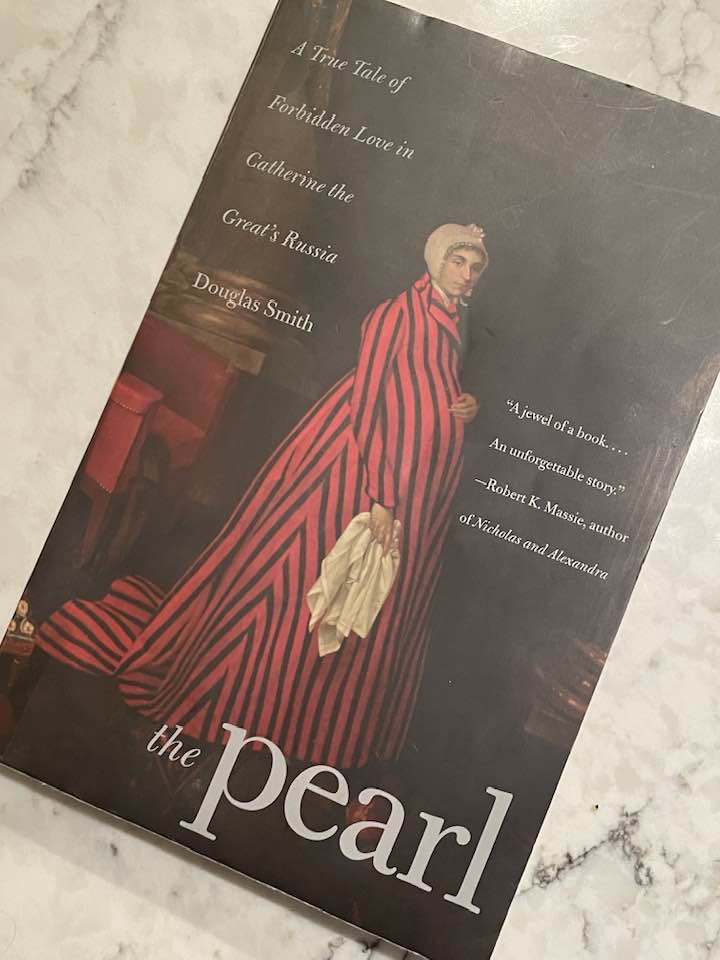

The subtitle of The Pearl is A True Tale of Forbidden Love in Catherine the Great’s Russia. The editor’s pick was apt, but the story covers enough to justify innumerable alternate subtitles: for example, A Window into Serfdom at the Turn of the 18th to 19th Century . . . or, Love Conquers All (Almost) . . . or, Old Russian Wealth Beyond Measure; or Riches and the Road to Destruction; or A Larger than Life Fairy Tale Filled with High Drama and Plenty of Tragedy . . . or Musical Mastery, Russian Style.

Opera (the real thing) plays a major role in this improbable tale of the meteoric rise of a serf—Praskovia—from desolate obscurity to national fame as a highly gifted stage singer and actress. But as in the best of opera, the heroine dies young, the hero ultimately dies of a broken heart, and between the rise and the fall of the curtain, the cast of characters—noble souls and wretched hearts; aristocracy and serfs; holy men and unholy pretenders—parade across the elaborate stage.

The central character in harmony with Praskovia is her master, mentor, lover, and ultimately, her husband—Count Nicholas Sheremetev, the wealthiest Russian of his generation. The Count’s paternal grandfather, Boris, a diplomat and army general, was a favorite of Peter the Great, especially after Boris defeated Sweden’s King Charles XII at Poltava (Ukraine) in 1709. Peter rewarded Boris handsomely with land, serfs and titles. This wealth was inherited by Boris’s son, also named Peter, who inherited more than wealth; he acquired his parents’ superb intellectual and dispositional genes. He would serve admirably under no fewer than seven consecutive Russian rulers from Peter the Great through the reign of Catherine the Great.

The most notable feature of Peter Sheremetev’s role in The Pearl, however, was the mighty wealth that he passed on to the main character of the story, his son, Nicholas. In contrast with our modern billionaires, Count Sheremetev’s wealth was measured by the vast territories, towns and villages and above all . . . the serfs attached to these holdings: 60,000 in all! (Contrast this with the largest slaveowner of the antebellum South, Joshua John Ward (South Carolina), who, at the time of his death in 1853, “owned” 1,131 slaves.) The “market value” of all these assets was inestimable, but Smith states that in 1798, Peter’s vast holdings generated an annual income of 630,000 rubles when by comparison, any Russian with an annual income of 9,000 rubles was considered rich.

Unlike his father, Nicholas had no interest in public service or in managing his sprawling estates across Russia. He was obsessed with theater and music, mainly opera. His goal was to build the best private theater that money could buy and impress his guests with the very best singers, actors, dancers, and instrumentalists that he could possibly find and develop. In those days, many noblemen created private theaters and most of their performers were serfs—trained and educated by their masters, but still, serfs, owned and controlled by the masters. Nicholas wished to outdo them all, and he had the resources to accomplish his goal.

To his credit, however, he himself had impressive musical skill and taste, and he excelled at identifying talent and potential among his thousands of serfs. Praskovia, the daughter of a blacksmith, was among them. She was brought into one of the household of Nicholas’s primary palace outside Moscow, and trained from a young age in theater arts and music, as well as an array of academic disciplines. She was assigned the name “Pearl,” in concert with several of her fellow female serf-performers, who were given nicknames associated with other precious gems.

It was common among the noblemen—just as it was among plantation owners of the South—to exploit their serfs in cruel and inhuman ways, and women, of course, faced sexual predation. Nicholas could be irascible and throw temper tantrums, but the purpose of his theater was to achieve the highest level of artistic excellence, not the lowest form of exploitation.

As Praskovia matured, she and Nicholas became “an item.” For a master and a serf to be “an item” was not unusual—illicit affairs were largely tolerated by society—but matrimony and all that was associated with it, such as titles, status, and inheritance, was severely condemned among the nobility. If it were made easy for master and slave, the whole edifice of serfdom would soon be jeopardized, threatening the entire social-political-economic order. (Cont.)

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2025 by Eric Nilsson