AUGUST 30, 2021 – The other day, my sister Jenny wrote a funny email to our other three sisters and me, describing the big music show in Central Park that Hurricane Henri cut short. As I chuckled at her descriptions of Andrea Bocelli, Jennifer Hudson, and Barry Manilow, I thought, Who will save this email? Who in the next generation or beyond will ever see this amusing letter? Nearly all correspondence in current times takes the form of text on a screen, and if saved at all, it’s put out to pasture on a server farm somewhere distant, inaccessible from the corridors of time.

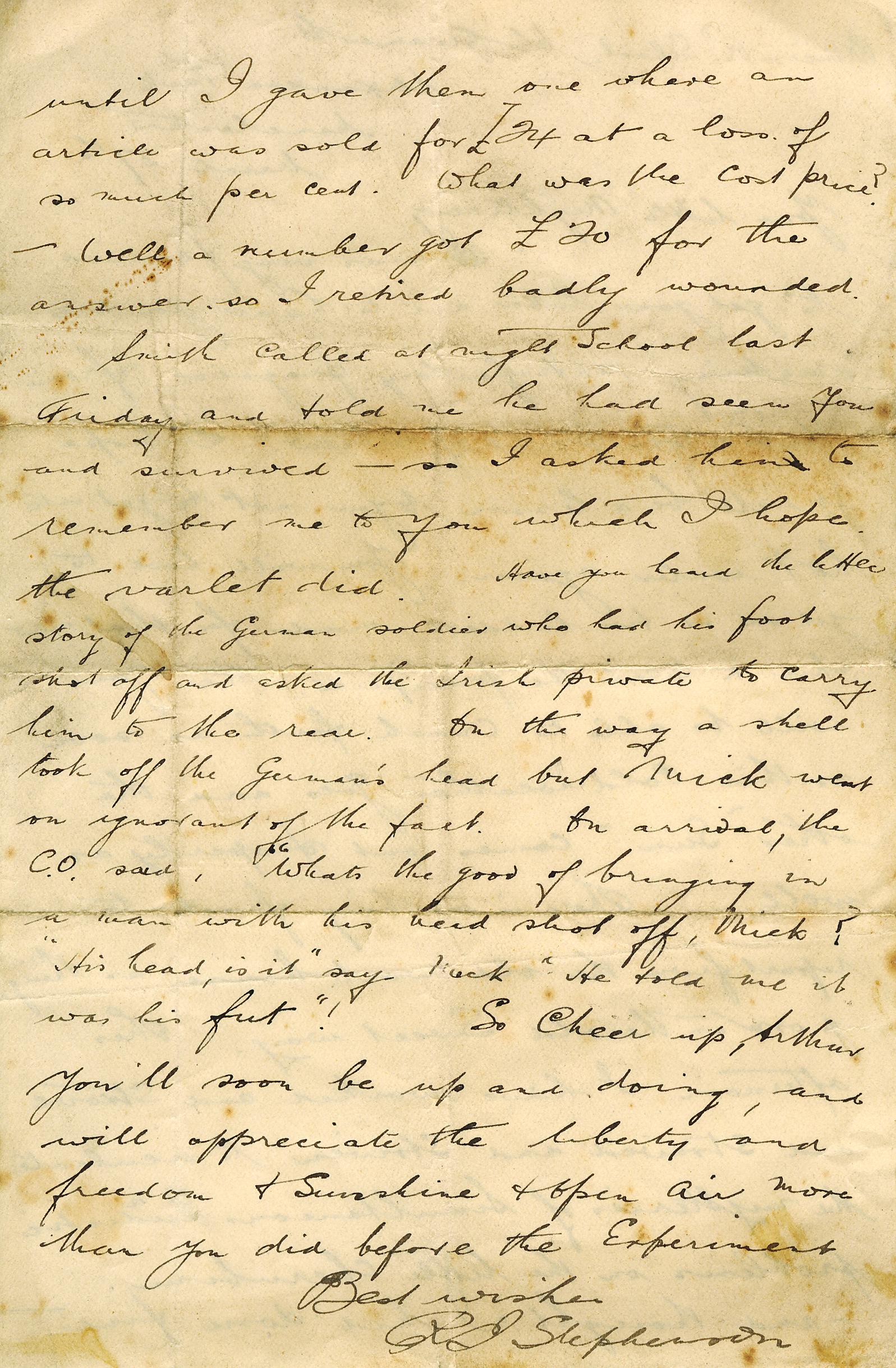

In another era, my sister’s message would’ve been preserved in paper form, tucked into an envelope, and stored in a box in the attic or a drawer of an old desk. Decades later someone would’ve discovered, held, and read thoughts and observations from the past.

Ironically, when writing and sending correspondence took so much more time and effort than banging out text and hitting “send,” letters were far longer and more substantive. Recently, I uncovered a copy of a letter my dad had written to a friend. The five-page, single-spaced “essay” was composed on a manual typewriter and contained many gems. Written in the summer of 1941, soon after my dad had turned 19, the letter made no mention of The War—the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor was still over the horizon.

For much of the letter, Dad wrote about his deep appreciation for classical music, and how no special training or education was required to discover the boundless beauty of music. “In spite of the countless books and articles written about music appreciation,” wrote Dad, “the authors of them all admit that there is really only one good way of learning to feel the meaning of music, and that is LISTENING TO IT.”

He went on to talk about the importance of knowing the lives of great composers and wrote out verbatim, the long, introductory paragraph of Beethoven’s Heiligenstadt Testament. Then came a quote from Shakespeare

The man that hath no music in himself,

Nor is not moved with concord of sweet sounds,

Is fit for treasons, stratagems, and spoils;

The motions of his spirit are dull as night,

And his affections dark as Erebus,

Let no such man be trusted.

Merchant of Venice, Act V.

Lord knows what happened to the original letter, but Dad kept a carbon copy, which wound up in the bottom of a trunk stored in the top of my parents’ house—the attic, of course!—to be uncovered 80 years later. What remains to be seen is what becomes of the carbon copy, and whether it will be “rediscovered,” held, and read 80 years henceforth.

For now, I find inspiration in Dad’s writing about his appreciation for music. His own inspiration from the words of the Bard and the Titan is icing on the cake.

What emails, tweets, and texts—and what icing-on-cake—will survive the moment of our time?

(Remember to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.)

© 2021 by Eric Nilsson