APRIL 21, 2025 – The semester is flying by—only three more classes of Russian History from Peter the Great to the Present led by the inimitable and indefatigable Professor Theofanis Stavrou. I am hoping that he’ll decide to sign on for yet another year of teaching at the University of Minnesota. There’s no reason to believe that he can’t, won’t or shouldn’t continue a stellar career that began in 1963.

This evening’s lecture, delivered with his usual enthusiasm and erudition, covered what Professor Stavrou called the “Ten Years that Shook the World,” a reference to John Reed’s classic about the October Revolution, Reds: Ten Days that Shook the World. The ten years covered the period from the end of Gorbachev’s regime on December 25, 1991—and with it, the end of the Soviet Union—to the beginning of Putin’s inauguration as president on May 2000. Boris Yeltsin was President of Russia during this period, during which, in many respects, Russia was a failed state or at most, the remnant of an empire.

According to Professor Stavrou, Gorbachev was very much an intellectual, free from corruption (affirmed by none other than Alexei Navalny), and at the start of his reign, intent on bringing meaningful reforms to an obviously broken system. When it came to nuclear war, Gorbachev was a total realist: from any rational perspective, nuclear conflict was simply not an option. He was an ardent believer in socialism and sought to initiate a “second socialist revolution.” Eventually, however, he realized that the system was too ossified for reform; beyond the hope of a “second revolution.”

Yeltsin was vehemently anti-communist, but if he started off espousing democratic rule, he turned to authoritarian rule by fiat—executive orders, if you will. The country descended into anarchy, in which a handful of greedy grabbers seized control of economic assets, made themselves into billionaires, and exported their profits to the detriment of the Russian economy. (To Yeltsin’s surprising credit, however, after his political career ended, the man known for his drinking binges went on a years-long reading binge. He read Russian history voraciously, covering 300 pages per day! He became obsessed with his place in that history, and sought to understand the past better than your average scholar. Who would’ve thought?)

By the end of the millennium, it was Putin’s turn. Young, disciplined, and trained in the ways and mentality of the former KGB, he struck a deal with the oligarchs: “I’ll let you make money, but you have to pay taxes and stay out of politics.” Those who followed this recipe did fine; those who didn’t wound up in prison, defenestrated or otherwise dead.

Amidst a stunning array of languages and ethnicities within Russia, Orthodox Christianity filled the need for adhesion, which had been lost with the fall of communism. Next to religion was brute force, as Putin unleashed on Chechnya.

The next lecture will be all about Putin—before I’ll have a chance to read the book that Professor Stavrou strongly recommended. “You cannot begin to understand Putin,” he said, “without reading this book—The Man without a Face: The Unlikely Rise of Vladimir Putin (2012) by Masha Gellem. The week after that will be dedicated to Russia’s “special military operations” in Ukraine—“war” by another name.

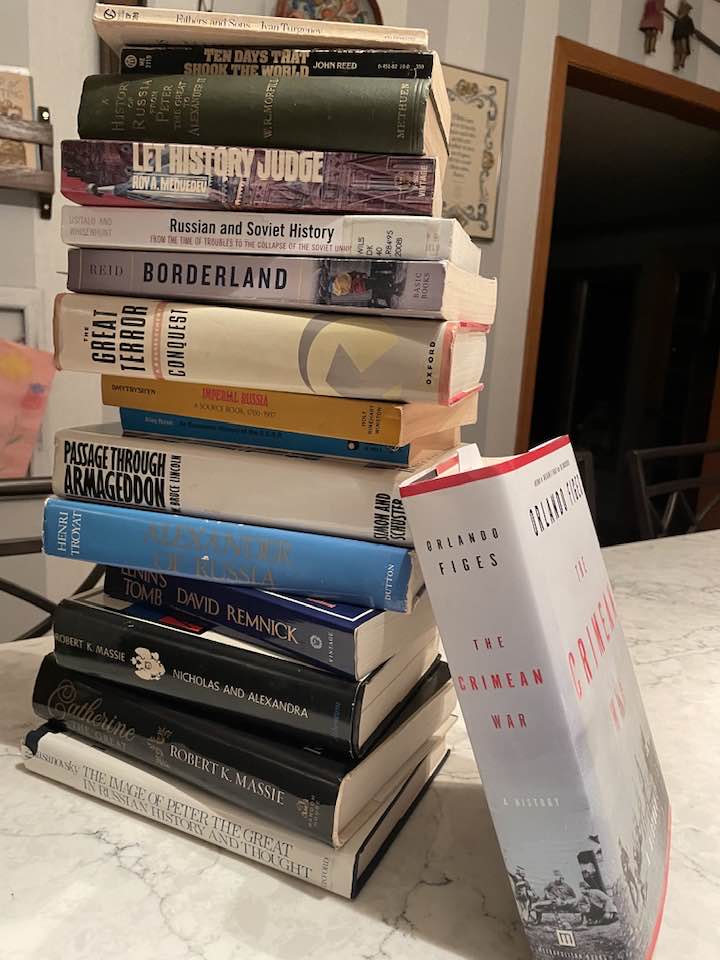

After class, we “Three Musketeers,” as Professor Stavrou calls my friends Matt and Ravi and me, engaged him in further discussion. We talked books, reading, and how the good professor keeps up on new scholarship. We learned that he gets by on only three hours of sleep a night, plus a cat nap in the afternoon. This explains how he’s able to read “a novel a week,” in addition to all his professional reading.

He said he was looking forward to lunch with us in two and a half weeks. I’d told him by email that we’d treat, but this evening he said that that was absolutely out of the question. “Everything will be taken care of,” he said, “and we will enjoy a wonderful conversation.”

Oh, what an honor, a privilege to have reached what Professor Stavrou calls the “third level of learning”: learning for the sheer joy of it—thanks to a professor whose own joy of learning is unceasingly inspirational.

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2025 by Eric Nilsson