SEPTEMBER 21, 2024 – After breakfast on the porch I ventured out to the dock to survey the unsettled weather. The wind was picking up from the southeast, and dark clouds lined the horizon. It wouldn’t take long for a clearer picture to form. By 10 o’clock the wind was roaring at 20 miles an hour, pushing whitecaps across the inland sea until they crashed along our shoreline. As I’d anticipated, the sulking sky opened a flow of rain. With outdoor projects placed on hold for the morning, I read for a bit from the captivating 600-page novel A Fine Balance by the extraordinary Indian writer Rohinton Mistry[1], but a dreary scene during the monsoon season in the Subcontinent reminded me of the gloom outside our windows. I looked through the upper story windows and watched the trees bend and twist in agitation. To counter the wily conditions outside and growing melancholy inside, I decided to attend to one of many “rainy day” indoor projects. But which “one”?

Since I’d been searching over the past couple of days for a long-lost book—A Child’s History of the World by V.M. Hillyer[2]—I decided to tackle . . . The Closet.

For years, this space in our upstairs bedroom has been the “homeless shelter” for an eclectic assortment of clothes, papers, books, boxes, craft wood, and a miscellany of orphaned objects with no other place to go except an off-site refuse collection center. You get the picture. Everyone has a “junk drawer.” I have a whole closet of junk, but then again, I come from a family that was in the moving and storage business. By the time I was in my 30s and the grand patriarch was in his 90s, the operative word for the business was storage, which is very much the mode applicable to The Closet.

One thing I learned from working for Grandpa one summer was spatial relationships. If he’d been an exceptionally bright bulb in his prime, in his declining years he retained his genius for fitting a mansion’s worth of furnishings into the minimum possible cubic storage space. I know this from having observed him direct the “muscle” in his warehouses. If I didn’t inherit his bulb wattage, I did acquire a knack for stuffing the maximum volume of odd stuff into an old closet—and getting the door to stay close.

As rain pelted the glass above the bedroom window seat next to the closet, I gingerly opened the bifold doors. I needn’t have held my breath. Nothing bonked me on the head or landed on my toe, and even the doors stayed on track. So far, so good. What greeted me, however, was a wall of stuff that reminded me of a trash compactor but without the usual odor. In fact, I caught a faint whiff of the great outdoors of the Pacific Northwest: packed in with everything else were cedar scraps I’d saved 29 years ago when I’d lined the storage box under the window seat.

My first task was the opposite of moving and storage. It was re-moving and scattering across every available surface of the bedroom, the tightly compressed inventory of the closet. Out came boxloads of slides; boxes filled with mementoes from my competitive running and skiing days; enough folding music stands for an orchestra; folded articles of clothing I hadn’t worn in decades; bags of ski wax; folders filled with correspondence; others with photographs (and negatives, of course!); sailing magazines; National Geographics; miscellaneous tools and parts; a bag of used sandpaper(!); two pairs of x-c racing skis (but only one pair of shoes); another bag full of ski wax and gear; my “New Member” folder from when I joined (for one season) the Minneapolis Rowing Club half a million years ago.

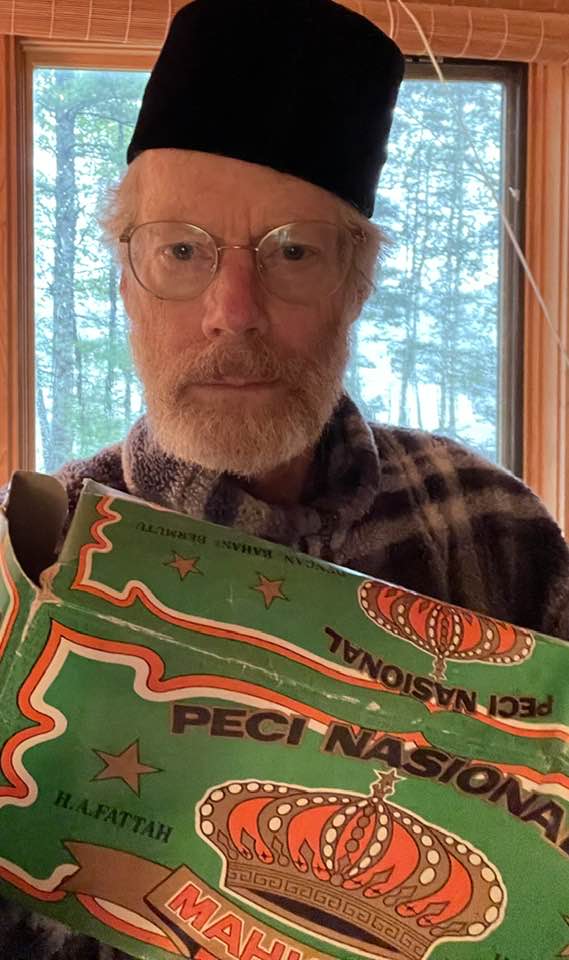

What won first prize, however, was inside a mystery bag that reminded me of an old Cracker Jack box—“Special Prize Inside.” When I peeked inside I saw a box from Indonesia, and inside the box, a beautiful songkok—or “peci.” It was a gift from my sister Jenny when she was on a five-star orchestra tour of the Far East. The black velvet Sukarno hat was so fine a thing I didn’t want to degrade it by use, so I’d consigned it to a permanent state of repose inside its funky box, which, in turn, found its own lifeless calm inside a bag stored in . . . The Closet.

I carefully removed the peci and donned it at what felt like a jaunty angle. Peering cautiously into the mirror, I jumped. What appeared was a man far older than his cap. The angle of the peci worked better for the cap than it did for the man. I returned it to the box, but not the box to the bag. And for the remainder of my mission I was careful to segregate the box from the pile of folded clothes filling the sofa and destined for Good Will.

Inside the “sports” box were photos, newspaper clippings, race results, a “Second Place” ribbon (my best); a Western Union telegram sent by a college friend the day before I flew to Boston for my first Boston Marathon, reading, “GOOD LUCK IN BOSTON ERIC!”; and finisher certificates from that marathon—the first one my mother had preserved for me in a cheap frame (with a “Anoka Drug” sticker on the back), subsequent certificates in various conditions ranging from “okay” to “ripped”; my daily detailed workout logs for the two most intense years of my efforts to run a sub-2:30.00 marathon (it wasn’t to be—the closest I came was 2:42.45, according to the official result card I received (and found in the box) after the Twin Cities Marathon in 1979 (at age 25).

Another box held a stash of small treasures—miscellaneous photos of Björnholm, no less; rejection letters saved from my first effort to get a book published (Campus Capers: The College Prankster’s Handbook); half a dozen blank, stamped, postcards pre-addressed to my parents to encourage me to write home from school; a postcard from mother herself telling about her trip from Minneapolis to Newark in June 1980 when thunderstorms forced the flight to re-route first to Washington, then Philly, then Harford, then Boston, then . . . to Newark after all (as they were getting low on fuel, she speculated); and a writing scrap from a more serious writing effort—an adventure novel. Torn from a spiral notebook was a page from a chapter, “The Last Letter Home.” It read,

Dear Folks,

Today Shenghi and I climbed to the top of Nunchit, one of the peaks just to the north of the lamasery. Except for a few squalls during the ascent, the weather was quite good, and we reached the summit without incident. It was my 25th climb of the season and in many respects the most enjoyable. Shenghi is an excellent climbing partner, and I prefer him to the other Sherpas. I rather think that he enjoyed today’s climb too.

As you can imagine, the view from the summit

That’s as far as the ink line went. I have no memory of the rest of the story or whatever happened to it. Perhaps the answer lies inside a folder in another box in another closet, but I’m not holding my breath.

As the memories filtered through my fingers, I felt the twinge of an old person’s melancholy. Unexpectedly, I’d exposed reminders that the game, the race, the play, the novel, the trial, the concert, the expedition through life was far closer to its dénouement than to its origin. And when the inevitable day arrives for someone to write a terse epilogue, that in turn will soon become its own disposable scrap.

None of what I saw and touched, none of the memories thus evoked, I realized, would matter to anyone. Not now while I still live and breathe, laugh and scowl; certainly not when I am no longer. If attention spans in our culture are short, memories are even shorter.

As noon approached and the rain stopped, I left the closet project and went for a walk in the tree garden. The millions—billions—of leaves and needles reminded me of all the words, numbers, and images inside The Closet; of all the billions of memories every human creates in life. Of what significance is any of them, I thought; of an individual leaf, needle, human memory or record?

Therein lies a paradox, I realized, a corollary to my central made-up paradoxical maxim (“At the same time absolutely nothing matters, absolutely everything does.”): by itself a single leaf, needle, thought, record, memory, has no significance, but in aggregate, all those trillions upon trillions of markers and memories are the stuff of life on earth, which, the last I checked with my star-gazing binoculars, is (most likely) the single most amazing place in our corner of the local stellar neighborhood.[3] A person shouldn’t yield to melancholy when the end of the journey is much closer than the beginning—any more than a single leaf or needle falling to the ground or a human memory fading (or being pitched into a dumpster) should be cause for despair about the state of the forest or the human condition.

The closet has been relieved of a surprising volume of stuff to be carted back home for proper disposal or recycling, as the case may be. The project failed to produce what had inspired it: A Child’s History of the World. At a loss, I ordered a 2020 reprint online. It will arrive in plenty of time for Illiana’s birthday. I can’t wait to see her open it—and then for us to read it together.

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2024 by Eric Nilsson

[1] Along with Swimming Lessons, a collection of short stories by Mistry, a gift from our next-door neighbor at the Cove in Connecticut.

[2] A classic first published in 1924 by V. M. Hillyer (1875-1931) first headmaster of the Calvert School of Baltimore. I’d discovered the book when our oldest son Cory was around nine years old. He loved it so, he insisted that I read from it every night before bedtime. Artfully written, the book allowed us to travel together through time—from the beginning of time through “The Great War.” Cory still talks about the book today—so often, in fact, that his daughter Illiana has now asked me several times to read it to her. I’d be thrilled to do so—if only I could find it. It was last seen at the Red Cabin, and my last memory of it was when a cabin guest read it, then commented, “Hmmm. There’s some racial stuff in here that you might want to take a look at.” I don’t remember off hand anything that was particularly jolting in that respect, though it’s been 30 years since I read the book to Cory. I wouldn’t be surprised, I guess, if it projects a perspective that would grate on modern sensibilities, quite apart from one’s level of “wokeness.” In any event, when necessary or appropriate, I can edit on the fly when I read to Illiana, and if we encounter a passage that’s beyond practicable editing, I’ll provide an explanation of how attitudes have evolved—at least to the best of my ability.

[3] I restrained myself from going overboard in scope.